A Jan. 12, 2016 American Institute of Physics (AIP) news release by John Arnst (also on EurekAlert but dated Jan. 14, 2016) describes computational research into self-assembling nanodevices based on porphine molecules,

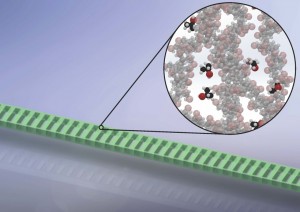

As we continue to shrink electronic components, top-down manufacturing methods begin to approach a physical limit at the nanoscale. Rather than continue to chip away at this limit, one solution of interest involves using the bottom-up self-assembly of molecular building blocks to build nanoscale devices.

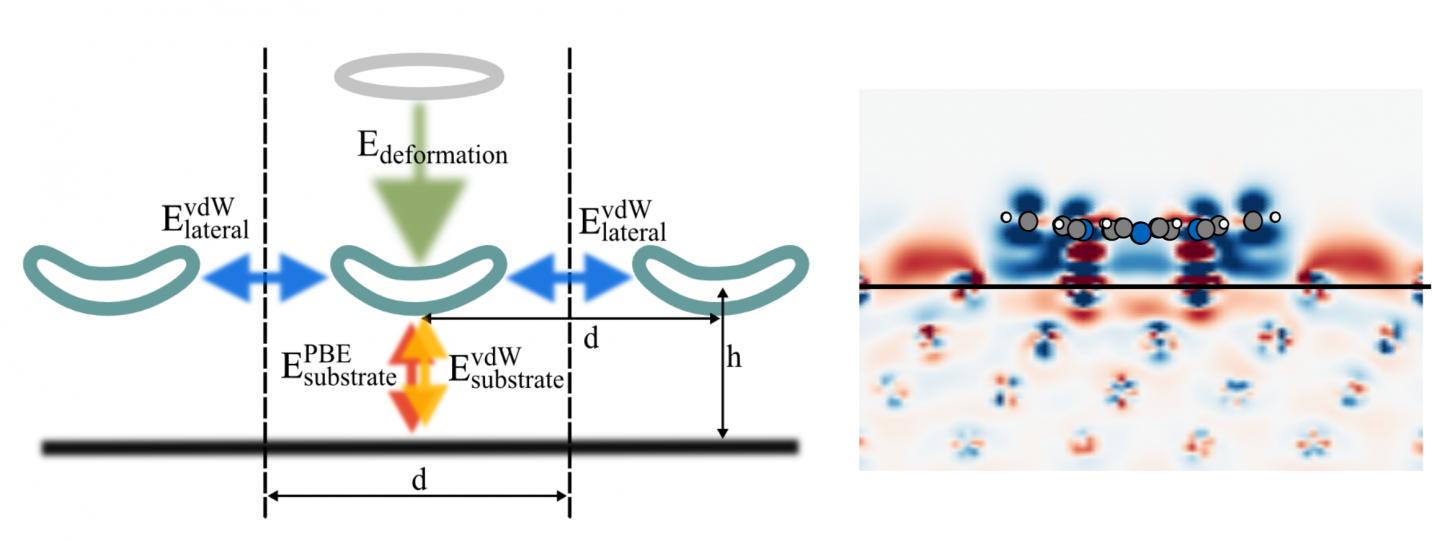

Successful self-assembly is an elaborately choreographed dance, in which the attractive and repulsive forces within molecules, between each molecule and its neighbors, and between molecules and the surface that supports them, have to all be taken into account. To better understand the self-assembly process, researchers at the Technical University of Munich have characterized the contributions of all interaction components, such as covalent bonding and van der Waals interactions between molecules and between molecules and a surface.

“In an ideal case, the smallest possible device has the size of a single atom or molecule,” said Katharina Diller, who worked as a postdoctoral researcher in the group of Karsten Reuter at the Technical University of Munich. Reuter and his colleagues present their work this week in The Journal of Chemical Physics, from AIP Publishing.

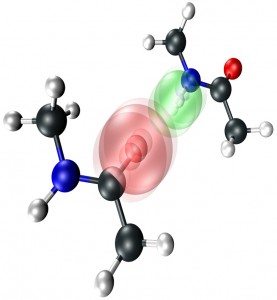

One such example is a single-porphyrin switch, which occupies a surface area of only one square nanometer. [emphasis mine] The porphine molecule, which was the object of this study, is even smaller than this. Porphyrins are a group of ringed chemical compounds which notably include heme – responsible for transporting oxygen and carbon dioxide in the bloodstream – and chlorophyll. In synthetically-derived applications, porphyrins are studied for their potential uses as sensors, light-sensitive dyes in organic solar cells, and molecular magnets.

The researchers from TU Munich assessed the interactions of the porphyrin molecule 2H-porphine by using density functional theory, a quantum mechanical computational modelling method used to describe the electronic properties of molecules and materials. Their simulations were performed at the high-performance supercomputer SuperMUC at Leibniz-Rechenzentrum in Garching.

The metallic substrates the researchers chose for the porphyrin molecules to assemble on, the close packed single crystal surfaces of copper and silver, are widely used as substrates in surface science. This is due to the densely packed nature of the surfaces, which allow the molecules to exhibit a smooth adsorption environment. Additionally, copper and silver each react differently with porhyrins – the molecule adsorbs more strongly on copper, whereas silver does a better job of keeping the electronic structure of the molecule intact – allowing the researchers to monitor a variety of competing effects for future applications.

In their simulation, porphyrin molecules were placed on a copper or silver slab, which was repeated periodically to simulate an extended surface. After finding the optimal geometry in which the molecules would adsorb on the surface, the researchers altered the size of the metal slab to increase or decrease the distance between molecules, thus simulating different molecular coverages. The computational setup gave them a switch to turn the energy contributions of neighboring molecules on and off, in order to observe the interplay of the individual interactions.

Diller and Reuter, along with colleagues Reinhard Maurer and Moritz Müller, who is first author on the paper, found that the weak long-range van der Waals interactions yielded the largest contribution to the molecule-surface interaction, and showed that the often employed methods to quantify the electronic charges in the system have to be used with caution. Surprisingly, while interactions directly between molecules are negligible, the researcher found indications for surface-mediated molecule-molecule interactions at higher molecular coverages.

“The analysis of the electronic structure and the individual interaction components allows us to better understand the self-assembly of porphine adsorbed on copper and silver, and additionally enables predictions for more complex porphyrine analogues,” Diller said. “These conclusions, however, come without yet considering the effects of atomic motion at finite temperature, which we did not study in this work.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Interfacial charge rearrangement and intermolecular interactions: Density-functional theory study of free-base porphine adsorbed on Ag(111) and Cu(111) by Moritz Müller, Katharina Diller, Reinhard J. Maurer, and Karsten Reuter. J. Chem. Phys. 144, 024701 (2016); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4938259

This paper appears to be open access.

Finally, the researchers have made this illustrative diagram titled ‘Energy’ available,