Psychedelic drugs seems to be enjoying a ‘moment’. After decades of being vilified and declared illegal (in many jurisdictions), psychedelic (or hallucinogenic) drugs are once again being tested for use in therapy. A Sept. 1, 2017 article by Diana Kwon for The Scientist describes some of the latest research (I’ve excerpted the section on molecules; Note: Links have been removed),

Mind-bending molecules

© SEAN MCCABE

All the classic psychedelic drugs—psilocybin, LSD, and N,N-dimethyltryptamine (DMT), the active component in ayahuasca—activate serotonin 2A (5-HT2A) receptors, which are distributed throughout the brain. In all likelihood, this receptor plays a key role in the drugs’ effects. Krähenmann [Rainer Krähenmann, a psychiatrist and researcher at the University of Zurich]] and his colleagues in Zurich have discovered that ketanserin, a 5-HT2A receptor antagonist, blocks LSD’s hallucinogenic properties and prevents individuals from entering a dreamlike state or attributing personal relevance to the experience.12,13

Other research groups have found that, in rodent brains, 2,5-dimethoxy-4-iodoamphetamine (DOI), a highly potent and selective 5-HT2A receptor agonist, can modify the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)—a protein that, among other things, regulates neuronal survival, differentiation, and synaptic plasticity. This has led some scientists to hypothesize that, through this pathway, psychedelics may enhance neuroplasticity, the ability to form new neuronal connections in the brain.14 “We’re still working on that and trying to figure out what is so special about the receptor and where it is involved,” says Katrin Preller, a postdoc studying psychedelics at the University of Zurich. “But it seems like this combination of serotonin 2A receptors and BDNF leads to a kind of different organizational state in the brain that leads to what people experience under the influence of psychedelics.”

This serotonin receptor isn’t limited to the central nervous system. Work by Charles Nichols, a pharmacology professor at Louisiana State University, has revealed that 5-HT2A receptor agonists can reduce inflammation throughout the body. Nichols and his former postdoc Bangning Yu stumbled upon this discovery by accident, while testing the effects of DOI on smooth muscle cells from rat aortas. When they added this drug to the rodent cells in culture, it blocked the effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), a key inflammatory cytokine.

“It was completely unexpected,” Nichols recalls. The effects were so bewildering, he says, that they repeated the experiment twice to convince themselves that the results were correct. Before publishing the findings in 2008,15 they tested a few other 5-HT2A receptor agonists, including LSD, and found consistent anti-inflammatory effects, though none of the drugs’ effects were as strong as DOI’s. “Most of the psychedelics I have tested are about as potent as a corticosteroid at their target, but there’s something very unique about DOI that makes it much more potent,” Nichols says. “That’s one of the mysteries I’m trying to solve.”

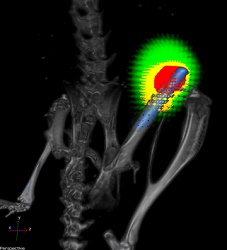

After seeing the effect these drugs could have in cells, Nichols and his team moved on to whole animals. When they treated mouse models of system-wide inflammation with DOI, they found potent anti-inflammatory effects throughout the rodents’ bodies, with the strongest effects in the small intestine and a section of the main cardiac artery known as the aortic arch.16 “I think that’s really when it felt that we were onto something big, when we saw it in the whole animal,” Nichols says.

The group is now focused on testing DOI as a potential therapeutic for inflammatory diseases. In a 2015 study, they reported that DOI could block the development of asthma in a mouse model of the condition,17 and last December, the team received a patent to use DOI for four indications: asthma, Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and irritable bowel syndrome. They are now working to move the treatment into clinical trials. The benefit of using DOI for these conditions, Nichols says, is that because of its potency, only small amounts will be required—far below the amounts required to produce hallucinogenic effects.

In addition to opening the door to a new class of diseases that could benefit from psychedelics-inspired therapy, Nichols’s work suggests “that there may be some enduring changes that are mediated through anti-inflammatory effects,” Griffiths [Roland Griffiths, a psychiatry professor at Johns Hopkins University] says. Recent studies suggest that inflammation may play a role in a number of psychological disorders, including depression18 and addiction.19

“If somebody has neuroinflammation and that’s causing depression, and something like psilocybin makes it better through the subjective experience but the brain is still inflamed, it’s going to fall back into the depressed rut,” Nichols says. But if psilocybin is also treating the inflammation, he adds, “it won’t have that rut to fall back into.”

…

If it turns out that psychedelics do have anti-inflammatory effects in the brain, the drugs’ therapeutic uses could be even broader than scientists now envision. “In terms of neurodegenerative disease, every one of these disorders is mediated by inflammatory cytokines,” says Juan Sanchez-Ramos, a neuroscientist at the University of South Florida who in 2013 reported that small doses of psilocybin could promote neurogenesis in the mouse hippocampus.20 “That’s why I think, with Alzheimer’s, for example, if you attenuate the inflammation, it could help slow the progression of the disease.”

For anyone who was never exposed to the anti-hallucinogenic drug campaigns, this turn of events is mindboggling. There was a great deal of concern especially with LSD in the 1960s and it was not entirely unfounded. In my own family, a distant cousin, while under the influence of the drug, jumped off a building believing he could fly. So, Kwon’s story opening with a story about someone being treated successfully for depression with a psychedelic drug was surprising to me . Why these drugs are being used successfully for psychiatric conditions when so much damage was apparently done under the influence in decades past may have something to do with taking the drugs in a controlled environment and, possibly, smaller dosages.