Who knew that spinach leaves could be turned into electronic devices? The answer is: engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, according to an Oct. 31, 2016 news item on phys.org,

Spinach is no longer just a superfood: By embedding leaves with carbon nanotubes, MIT engineers have transformed spinach plants into sensors that can detect explosives and wirelessly relay that information to a handheld device similar to a smartphone.

This is one of the first demonstrations of engineering electronic systems into plants, an approach that the researchers call “plant nanobionics.”

An Oct. 31, 2016 MIT news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the research further (Note: Links have been removed),

“The goal of plant nanobionics is to introduce nanoparticles into the plant to give it non-native functions,” says Michael Strano, the Carbon P. Dubbs Professor of Chemical Engineering at MIT and the leader of the research team.

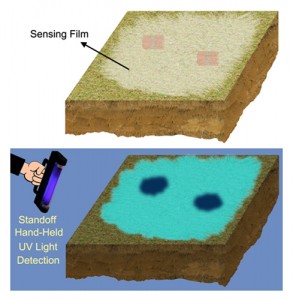

In this case, the plants were designed to detect chemical compounds known as nitroaromatics, which are often used in landmines and other explosives. When one of these chemicals is present in the groundwater sampled naturally by the plant, carbon nanotubes embedded in the plant leaves emit a fluorescent signal that can be read with an infrared camera. The camera can be attached to a small computer similar to a smartphone, which then sends an email to the user.

“This is a novel demonstration of how we have overcome the plant/human communication barrier,” says Strano, who believes plant power could also be harnessed to warn of pollutants and environmental conditions such as drought.

Strano is the senior author of a paper describing the nanobionic plants in the Oct. 31 [2016] issue of Nature Materials. The paper’s lead authors are Min Hao Wong, an MIT graduate student who has started a company called Plantea to further develop this technology, and Juan Pablo Giraldo, a former MIT postdoc who is now an assistant professor at the University of California at Riverside.

Environmental monitoring

Two years ago, in the first demonstration of plant nanobionics, Strano and former MIT postdoc Juan Pablo Giraldo used nanoparticles to enhance plants’ photosynthesis ability and to turn them into sensors for nitric oxide, a pollutant produced by combustion.

Plants are ideally suited for monitoring the environment because they already take in a lot of information from their surroundings, Strano says.

“Plants are very good analytical chemists,” he says. “They have an extensive root network in the soil, are constantly sampling groundwater, and have a way to self-power the transport of that water up into the leaves.”

Strano’s lab has previously developed carbon nanotubes that can be used as sensors to detect a wide range of molecules, including hydrogen peroxide, the explosive TNT, and the nerve gas sarin. When the target molecule binds to a polymer wrapped around the nanotube, it alters the tube’s fluorescence.

In the new study, the researchers embedded sensors for nitroaromatic compounds into the leaves of spinach plants. Using a technique called vascular infusion, which involves applying a solution of nanoparticles to the underside of the leaf, they placed the sensors into a leaf layer known as the mesophyll, which is where most photosynthesis takes place.

They also embedded carbon nanotubes that emit a constant fluorescent signal that serves as a reference. This allows the researchers to compare the two fluorescent signals, making it easier to determine if the explosive sensor has detected anything. If there are any explosive molecules in the groundwater, it takes about 10 minutes for the plant to draw them up into the leaves, where they encounter the detector.

To read the signal, the researchers shine a laser onto the leaf, prompting the nanotubes in the leaf to emit near-infrared fluorescent light. This can be detected with a small infrared camera connected to a Raspberry Pi, a $35 credit-card-sized computer similar to the computer inside a smartphone. The signal could also be detected with a smartphone by removing the infrared filter that most camera phones have, the researchers say.

“This setup could be replaced by a cell phone and the right kind of camera,” Strano says. “It’s just the infrared filter that would stop you from using your cell phone.”

Using this setup, the researchers can pick up a signal from about 1 meter away from the plant, and they are now working on increasing that distance.

Michael McAlpine, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Minnesota, says this approach holds great potential for engineering not only sensors but many other kinds of bionic plants that might receive radio signals or change color.

“When you have manmade materials infiltrated into a living organism, you can have plants do things that plants don’t ordinarily do,” says McAlpine, who was not involved in the research. “Once you start to think of living organisms like plants as biomaterials that can be combined with electronic materials, this is all possible.”

“A wealth of information”

In the 2014 plant nanobionics study, Strano’s lab worked with a common laboratory plant known as Arabidopsis thaliana. However, the researchers wanted to use common spinach plants for the latest study, to demonstrate the versatility of this technique. “You can apply these techniques with any living plant,” Strano says.

So far, the researchers have also engineered spinach plants that can detect dopamine, which influences plant root growth, and they are now working on additional sensors, including some that track the chemicals plants use to convey information within their own tissues.

“Plants are very environmentally responsive,” Strano says. “They know that there is going to be a drought long before we do. They can detect small changes in the properties of soil and water potential. If we tap into those chemical signaling pathways, there is a wealth of information to access.”

These sensors could also help botanists learn more about the inner workings of plants, monitor plant health, and maximize the yield of rare compounds synthesized by plants such as the Madagascar periwinkle, which produces drugs used to treat cancer.

“These sensors give real-time information from the plant. It is almost like having the plant talk to us about the environment they are in,” Wong says. “In the case of precision agriculture, having such information can directly affect yield and margins.”

Once getting over the excitement, questions spring to mind. How could this be implemented? Is somebody going to plant a field of spinach and then embed the leaves so they can detect landmines? How will anyone know where to plant the spinach? And on a different track, is this spinach edible? I suspect that if spinach can be successfully used as a sensor, it might not be for explosives but for pollution as the researchers suggest.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nitroaromatic detection and infrared communication from wild-type plants using plant nanobionics by Min Hao Wong, Juan P. Giraldo, Seon-Yeong Kwak, Volodymyr B. Koman, Rosalie Sinclair, Tedrick Thomas Salim Lew, Gili Bisker, Pingwei Liu, & Michael S. Strano. Nature Materials (2016) doi:10.1038/nmat4771 Published online 31 October 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.

The last posting here which featured Strano’s research is in an Aug. 25, 2015 piece about carbon nanotubes and medical sensors.