A February 10, 2022 news item on ScienceDaily announces research on a biohybrid fish,

Harvard University researchers, in collaboration with colleagues from Emory University, have developed the first fully autonomous biohybrid fish from human stem-cell derived cardiac muscle cells. The artificial fish swims by recreating the muscle contractions of a pumping heart, bringing researchers one step closer to developing a more complex artificial muscular pump and providing a platform to study heart disease like arrhythmia.

…

A February 10, 2022 Harvard University John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences news release (also on EurekAlert) by Leah Burrows explains how this research could lead to an artificial heart (Note: Links have been removed),

“Our ultimate goal is to build an artificial heart to replace a malformed heart in a child,” said Kit Parker, the Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics at the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS) and senior author of the paper. “Most of the work in building heart tissue or hearts, including some work we have done, is focused on replicating the anatomical features or replicating the simple beating of the heart in the engineered tissues. But here, we are drawing design inspiration from the biophysics of the heart, which is harder to do. Now, rather than using heart imaging as a blueprint, we are identifying the key biophysical principles that make the heart work, using them as design criteria, and replicating them in a system, a living, swimming fish, where it is much easier to see if we are successful.”

The research is published in Science.

The biohybrid fish developed by the team builds off previous research from Parker’s Disease Biophysics Group. In 2012, the lab used cardiac muscle cells from rats to build a jellyfish-like biohybrid pump and in 2016 the researchers developed a swimming, artificial stingray also from rat heart muscle cells.

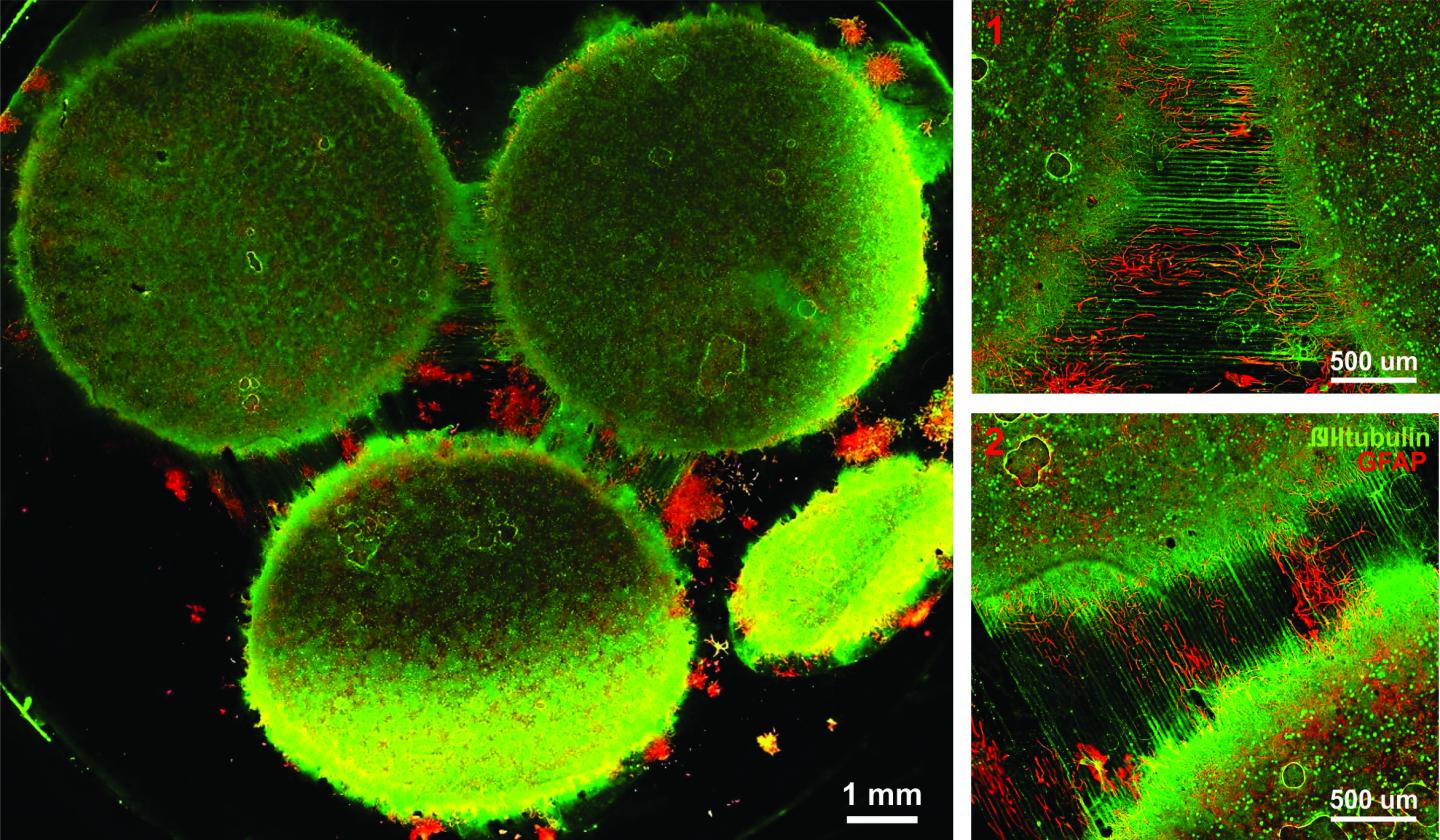

In this research, the team built the first autonomous biohybrid device made from human stem-cell derived cardiomyocytes. This device was inspired by the shape and swimming motion of a zebrafish. Unlike previous devices, the biohybrid zebrafish has two layers of muscle cells, one on each side of the tail fin. When one side contracts, the other stretches. That stretch triggers the opening of a mechanosensitive protein channel, which causes a contraction, which triggers a stretch and so on and so forth, leading to a closed loop system that can propel the fish for more than 100 days.

“By leveraging cardiac mechano-electrical signaling between two layers of muscle, we recreated the cycle where each contraction results automatically as a response to the stretching on the opposite side,” said Keel Yong Lee, a postdoctoral fellow at SEAS and co-first author of the study. “The results highlight the role of feedback mechanisms in muscular pumps such as the heart.”

The researchers also engineered an autonomous pacing node, like a pacemaker, which controls the frequency and rhythm of these spontaneous contractions. Together, the two layers of muscle and the autonomous pacing node enabled the generation of continuous, spontaneous, and coordinated, back-and-forth fin movements.

“Because of the two internal pacing mechanisms, our fish can live longer, move faster and swim more efficiently than previous work,” said Sung-Jin Park, a former postdoctoral fellow in the Disease Biophysics Group at SEAS and co-first author of the study. “This new research provides a model to investigate mechano-electrical signaling as a therapeutic target of heart rhythm management and for understanding pathophysiology in sinoatrial node dysfunctions and cardiac arrhythmia.”

Park is currently an Assistant Professor at the Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University School of Medicine.

Unlike a fish in your refrigerator, this biohybrid fish improves with age. Its muscle contraction amplitude, maximum swimming speed, and muscle coordination all increased for the first month as the cardiomyocyte cells matured. Eventually, the biohybrid fish reached speeds and swimming efficacy similar to zebrafish in the wild.

Next, the team aims to build even more complex biohybrid devices from human heart cells.

“I could build a model heart out of Play-Doh, it doesn’t mean I can build a heart,” said Parker. “You can grow some random tumor cells in a dish until they curdle into a throbbing lump and call it a cardiac organoid. Neither of those efforts is going to, by design, recapitulate the physics of a system that beats over a billion times during your lifetime while simultaneously rebuilding its cells on the fly. That is the challenge. That is where we go to work.”

The research was co-authored by David G. Matthews, Sean L. Kim, Carlos Antonio Marquez, John F. Zimmerman, Herdeline Ann M. Ardona, Andre G. Kleber and George V. Lauder.

It was supported in part by National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grant UH3TR000522, and National Science Foundation Materials Research Science and Engineering Center grant DMR-142057.

Before giving you a link and a citation for the paper, here’s a little more information about the work from a February 10, 2022 American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) news release on EurekAlert announcing publication of the paper in their journal Science, Note: A link has been removed,

An autonomously swimming biohybrid fish, designed with a focus on two key regulatory features of the human heart, has revealed the importance of feedback mechanisms in muscular pumps (such as the heart). The findings could one day help inform the development of an artificial heart made from living muscle cells. Biohybrid systems – devices containing both biological and artificial components – are an effective way to investigate the physiological control mechanisms in biological organisms and to discover bio-inspired robotic solutions to a host of pressing concerns, including those related to human health. When it comes to natural fluid transport pumps, like those that circulate blood, the performance of biohybrid systems has been lacking, however. Here, researchers considered whether two functional regulatory features of the heart — mechanoelectrical signaling and automaticity — could be transferred to a synthetic analog of another fluid transport system: a swimming fish. Lee et al. developed an autonomously swimming fish constructed from a bilayer of human cardiac cells; the muscular bilayer was integrated using tissue engineering techniques. Lee and team were able to control muscle contractions in the biohybrid fish using external optogenetic stimulation, allowing the fish analog to swim. In tests, the biohybrid fish outperformed the locomotory speed of previous biohybrid muscular systems, the authors say. It maintained spontaneous activity for 108 days. By contrast, say the authors, biohybrid fish equipped with single-layered muscle showed deteriorating activity within the first month. The data in this study demonstrate the potential of muscular bilayer systems and mechanoelectrical signaling as a means to promote maturation of in vitro muscle tissues, write Lee and colleagues. “Taken together,” the authors conclude, “the technology described here may represent foundational work toward the goal of creating autonomous systems capable of homeostatic regulation and adaptive behavioral control.”

For reporters interested in trends, this work builds upon previous work published in a July 2016 study in Science, in which Sung-jin Park et al. used cardiac cells from rats to develop a self-propelling ray fish analog.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

An autonomously swimming biohybrid fish designed with human cardiac biophysics by Keel Yong Lee, Sung-Jin Park, David G. Matthews. Sean L. Kim, Carlos Antonio Marquez, John F. Zimmerman, Herdeline Ann M. Ardoña, Andre G. Kleber, George V. Lauder and Kevin Kit Parker. Science • 10 Feb 2022 • Vol 375, Issue 6581 • pp. 639-647 • DOI: 10.1126/science.abh0474

This paper is behind a paywall.