Libraries, archives, records management, oral history, etc. there are many institutions and names for how we manage collective and personal memory. You might call it a peculiarly human obsession stretching back into antiquity. For example, there’s the Library of Alexandria (Wikipedia entry) founded in the third, or possibly 2nd, century BCE (before the common era) and reputed to store all the knowledge in the world. It was destroyed although accounts differ as to when and how but its loss remains a potent reminder of memory’s fragility.

These days, the technology community is terribly concerned with storing ever more bits of data on materials that are reaching their limits for storage.I have news of a possible solution, an interview of sorts with the researchers working on this new technology, and some very recent research into policies for cryptocurrency mining and development. That bit about cryptocurrency makes more sense when you read what the response to one of the interview questions.

Memory

It seems University of Alberta researchers may have found a way to increase memory exponentially, from a July 23, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily,

The most dense solid-state memory ever created could soon exceed the capabilities of current computer storage devices by 1,000 times, thanks to a new technique scientists at the University of Alberta have perfected.

“Essentially, you can take all 45 million songs on iTunes and store them on the surface of one quarter,” said Roshan Achal, PhD student in Department of Physics and lead author on the new research. “Five years ago, this wasn’t even something we thought possible.”

A July 23, 2018 University of Alberta news release (also on EurekAlert) by Jennifer-Anne Pascoe, which originated the news item, provides more information,

Previous discoveries were stable only at cryogenic conditions, meaning this new finding puts society light years closer to meeting the need for more storage for the current and continued deluge of data. One of the most exciting features of this memory is that it’s road-ready for real-world temperatures, as it can withstand normal use and transportation beyond the lab.

“What is often overlooked in the nanofabrication business is actual transportation to an end user, that simply was not possible until now given temperature restrictions,” continued Achal. “Our memory is stable well above room temperature and precise down to the atom.”

Achal explained that immediate applications will be data archival. Next steps will be increasing readout and writing speeds, meaning even more flexible applications.

More memory, less space

Achal works with University of Alberta physics professor Robert Wolkow, a pioneer in the field of atomic-scale physics. Wolkow perfected the art of the science behind nanotip technology, which, thanks to Wolkow and his team’s continued work, has now reached a tipping point, meaning scaling up atomic-scale manufacturing for commercialization.

“With this last piece of the puzzle now in-hand, atom-scale fabrication will become a commercial reality in the very near future,” said Wolkow. Wolkow’s Spin-off [sic] company, Quantum Silicon Inc., is hard at work on commercializing atom-scale fabrication for use in all areas of the technology sector.

To demonstrate the new discovery, Achal, Wolkow, and their fellow scientists not only fabricated the world’s smallest maple leaf, they also encoded the entire alphabet at a density of 138 terabytes, roughly equivalent to writing 350,000 letters across a grain of rice. For a playful twist, Achal also encoded music as an atom-sized song, the first 24 notes of which will make any video-game player of the 80s and 90s nostalgic for yesteryear but excited for the future of technology and society.

As noted in the news release, there is an atom-sized song, which is available in this video,

As for the nano-sized maple leaf, I highlighted that bit of whimsy in a June 30, 2017 posting.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Lithography for robust and editable atomic-scale silicon devices and memories by Roshan Achal, Mohammad Rashidi, Jeremiah Croshaw, David Churchill, Marco Taucer, Taleana Huff, Martin Cloutier, Jason Pitters, & Robert A. Wolkow. Nature Communicationsvolume 9, Article number: 2778 (2018) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-05171-y Published 23 July 2018

This paper is open access.

For interested parties, you can find Quantum Silicon (QSI) here. My Edmonton geography is all but nonexistent, still, it seems to me the company address on Saskatchewan Drive is a University of Alberta address. It’s also the address for the National Research Council of Canada. Perhaps this is a university/government spin-off company?

The ‘interview’

I sent some questions to the researchers at the University of Alberta who very kindly provided me with the following answers. Roshan Achal passed on one of the questions to his colleague Taleana Huff for her response. Both Achal and Huff are associated with QSI.

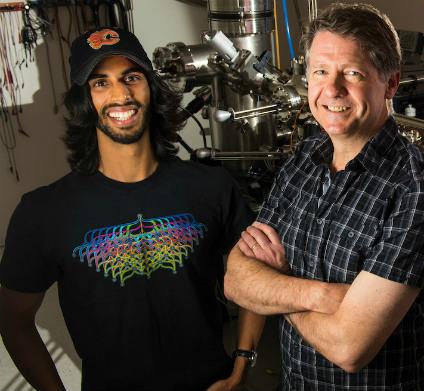

Unfortunately I could not find any pictures of all three researchers (Achal, Huff, and Wolkow) together.

Roshan Achal (left) used nanotechnology perfected by his PhD supervisor, Robert Wolkow (right) to create atomic-scale computer memory that could exceed the capacity of today’s solid-state storage drives by 1,000 times. (Photo: Faculty of Science)

(1) SHRINKING THE MANUFACTURING PROCESS TO THE ATOMIC SCALE HAS

ATTRACTED A LOT OF ATTENTION OVER THE YEARS STARTING WITH SCIENCE

FICTION OR RICHARD FEYNMAN OR K. ERIC DREXLER, ETC. IN ANY EVENT, THE

ORIGINS ARE CONTESTED SO I WON’T PUT YOU ON THE SPOT BY ASKING WHO

STARTED IT ALL INSTEAD ASKING HOW DID YOU GET STARTED?

I got started in this field about 6 years ago, when I undertook a MSc

with Dr. Wolkow here at the University of Alberta. Before that point, I

had only ever heard of a scanning tunneling microscope from what was

taught in my classes. I was aware of the famous IBM logo made up from

just a handful of atoms using this machine, but I didn’t know what

else could be done. Here, Dr. Wolkow introduced me to his line of

research, and I saw the immense potential for growth in this area and

decided to pursue it further. I had the chance to interact with and

learn from nanofabrication experts and gain the skills necessary to

begin playing around with my own techniques and ideas during my PhD.

(2) AS I UNDERSTAND IT, THESE ARE THE PIECES YOU’VE BEEN

WORKING ON: (1) THE TUNGSTEN MICROSCOPE TIP, WHICH MAKE[s] (2) THE SMALLEST

QUANTUM DOTS (SINGLE ATOMS OF SILICON), (3) THE AUTOMATION OF THE

QUANTUM DOT PRODUCTION PROCESS, AND (4) THE “MOST DENSE SOLID-STATE

MEMORY EVER CREATED.” WHAT’S MISSING FROM THE LIST AND IS THAT WHAT

YOU’RE WORKING ON NOW?

One of the things missing from the list, that we are currently working

on, is the ability to easily communicate (electrically) from the

macroscale (our world) to the nanoscale, without the use of a scanning

tunneling microscope. With this, we would be able to then construct

devices using the other pieces we’ve developed up to this point, and

then integrate them with more conventional electronics. This would bring

us yet another step closer to the realization of atomic-scale

electronics.

(3) PERHAPS YOU COULD CLARIFY SOMETHING FOR ME. USUALLY WHEN SOLID STATE

MEMORY IS MENTIONED, THERE’S GREAT CONCERN ABOUT MOORE’S LAW. IS

THIS WORK GOING TO CREATE A NEW LAW? AND, WHAT IF ANYTHING DOES

;YOUR MEMORY DEVICE HAVE TO DO WITH QUANTUM COMPUTING?

That is an interesting question. With the density we’ve achieved,

there are not too many surfaces where atomic sites are more closely

spaced to allow for another factor of two improvement. In that sense, it

would be difficult to improve memory densities further using these

techniques alone. In order to continue Moore’s law, new techniques, or

storage methods would have to be developed to move beyond atomic-scale

storage.

The memory design itself does not have anything to do with quantum

computing, however, the lithographic techniques developed through our

work, may enable the development of certain quantum-dot-based quantum

computing schemes.

(4) THIS MAY BE A LITTLE OUT OF LEFT FIELD (OR FURTHER OUT THAN THE

OTHERS), COULD;YOUR MEMORY DEVICE HAVE AN IMPACT ON THE

DEVELOPMENT OF CRYPTOCURRENCY AND BLOCKCHAIN? IF SO, WHAT MIGHT THAT

IMPACT BE?

I am not very familiar with these topics, however, co-author Taleana

Huff has provided some thoughts:

Taleana Huff (downloaded from https://ca.linkedin.com/in/taleana-huff]

“The memory, as we’ve designed it, might not have too much of an

impact in and of itself. Cryptocurrencies fall into two categories.

Proof of Work and Proof of Stake. Proof of Work relies on raw

computational power to solve a difficult math problem. If you solve it,

you get rewarded with a small amount of that coin. The problem is that

it can take a lot of power and energy for your computer to crunch

through that problem. Faster access to memory alone could perhaps

streamline small parts of this slightly, but it would be very slight.

Proof of Stake is already quite power efficient and wouldn’t really

have a drastic advantage from better faster computers.

Now, atomic-scale circuitry built using these new lithographic

techniques that we’ve developed, which could perform computations at

significantly lower energy costs, would be huge for Proof of Work coins.

One of the things holding bitcoin back, for example, is that mining it

is now consuming power on the order of the annual energy consumption

required by small countries. A more efficient way to mine while still

taking the same amount of time to solve the problem would make bitcoin

much more attractive as a currency.”

Thank you to Roshan Achal and Taleana Huff for helping me to further explore the implications of their work with Dr. Wolkow.

Comments

As usual, after receiving the replies I have more questions but these people have other things to do so I’ll content myself with noting that there is something extraordinary in the fact that we can imagine a near future where atomic scale manufacturing is possible and where as Achal says, ” … storage methods would have to be developed to move beyond atomic-scale [emphasis mine] storage”. In decades past it was the stuff of science fiction or of theorists who didn’t have the tools to turn the idea into a reality. With Wolkow’s, Achal’s, Hauff’s, and their colleagues’ work, atomic scale manufacturing is attainable in the foreseeable future.

Hopefully we’ll be wiser than we have been in the past in how we deploy these new manufacturing techniques. Of course, before we need the wisdom, scientists, as Achal notes, need to find a new way to communicate between the macroscale and the nanoscale.

As for Huff’s comments about cryptocurrencies and cyptocurrency and blockchain technology, I stumbled across this very recent research, from a July 31, 2018 Elsevier press release (also on EurekAlert),

A study [behind a paywall] published in Energy Research & Social Science warns that failure to lower the energy use by Bitcoin and similar Blockchain designs may prevent nations from reaching their climate change mitigation obligations under the Paris Agreement.

The study, authored by Jon Truby, PhD, Assistant Professor, Director of the Centre for Law & Development, College of Law, Qatar University, Doha, Qatar, evaluates the financial and legal options available to lawmakers to moderate blockchain-related energy consumption and foster a sustainable and innovative technology sector. Based on this rigorous review and analysis of the technologies, ownership models, and jurisdictional case law and practices, the article recommends an approach that imposes new taxes, charges, or restrictions to reduce demand by users, miners, and miner manufacturers who employ polluting technologies, and offers incentives that encourage developers to create less energy-intensive/carbon-neutral Blockchain.

“Digital currency mining is the first major industry developed from Blockchain, because its transactions alone consume more electricity than entire nations,” said Dr. Truby. “It needs to be directed towards sustainability if it is to realize its potential advantages.

“Many developers have taken no account of the environmental impact of their designs, so we must encourage them to adopt consensus protocols that do not result in high emissions. Taking no action means we are subsidizing high energy-consuming technology and causing future Blockchain developers to follow the same harmful path. We need to de-socialize the environmental costs involved while continuing to encourage progress of this important technology to unlock its potential economic, environmental, and social benefits,” explained Dr. Truby.

As a digital ledger that is accessible to, and trusted by all participants, Blockchain technology decentralizes and transforms the exchange of assets through peer-to-peer verification and payments. Blockchain technology has been advocated as being capable of delivering environmental and social benefits under the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals. However, Bitcoin’s system has been built in a way that is reminiscent of physical mining of natural resources – costs and efforts rise as the system reaches the ultimate resource limit and the mining of new resources requires increasing hardware resources, which consume huge amounts of electricity.

Putting this into perspective, Dr. Truby said, “the processes involved in a single Bitcoin transaction could provide electricity to a British home for a month – with the environmental costs socialized for private benefit.

“Bitcoin is here to stay, and so, future models must be designed without reliance on energy consumption so disproportionate on their economic or social benefits.”

The study evaluates various Blockchain technologies by their carbon footprints and recommends how to tax or restrict Blockchain types at different phases of production and use to discourage polluting versions and encourage cleaner alternatives. It also analyzes the legal measures that can be introduced to encourage technology innovators to develop low-emissions Blockchain designs. The specific recommendations include imposing levies to prevent path-dependent inertia from constraining innovation:

- Registration fees collected by brokers from digital coin buyers.

- “Bitcoin Sin Tax” surcharge on digital currency ownership.

- Green taxes and restrictions on machinery purchases/imports (e.g. Bitcoin mining machines).

- Smart contract transaction charges.

According to Dr. Truby, these findings may lead to new taxes, charges or restrictions, but could also lead to financial rewards for innovators developing carbon-neutral Blockchain.

The press release doesn’t fully reflect Dr. Truby’s thoughtfulness or the incentives he has suggested. it’s not all surcharges, taxes, and fees constitute encouragement. Here’s a sample from the conclusion,

The possibilities of Blockchain are endless and incentivisation can help solve various climate change issues, such as through the development of digital currencies to fund climate finance programmes. This type of public-private finance initiative is envisioned in the Paris Agreement, and fiscal tools can incentivize innovators to design financially rewarding Blockchain technology that also achieves environmental goals. Bitcoin, for example, has various utilitarian intentions in its White Paper, which may or may not turn out to be as envisioned, but it would not have been such a success without investors seeking remarkable returns. Embracing such technology, and promoting a shift in behaviour with such fiscal tools, can turn the industry itself towards achieving innovative solutions for environmental goals.

I realize Wolkow, et. al, are not focused on cryptocurrency and blockchain technology per se but as Huff notes in her reply, “… new lithographic techniques that we’ve developed, which could perform computations at significantly lower energy costs, would be huge for Proof of Work coins.”

Whether or not there are implications for cryptocurrencies, energy needs, climate change, etc., it’s the kind of innovative work being done by scientists at the University of Alberta which may have implications in fields far beyond the researchers’ original intentions such as more efficient computation and data storage.

ETA Aug. 6, 2018: Dexter Johnson weighed in with an August 3, 2018 posting on his Nanoclast blog (on the IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers] website),

Researchers at the University of Alberta in Canada have developed a new approach to rewritable data storage technology by using a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) to remove and replace hydrogen atoms from the surface of a silicon wafer. If this approach realizes its potential, it could lead to a data storage technology capable of storing 1,000 times more data than today’s hard drives, up to 138 terabytes per square inch.

As a bit of background, Gerd Binnig and Heinrich Rohrer developed the first STM in 1986 for which they later received the Nobel Prize in physics. In the over 30 years since an STM first imaged an atom by exploiting a phenomenon known as tunneling—which causes electrons to jump from the surface atoms of a material to the tip of an ultrasharp electrode suspended a few angstroms above—the technology has become the backbone of so-called nanotechnology.

In addition to imaging the world on the atomic scale for the last thirty years, STMs have been experimented with as a potential data storage device. Last year, we reported on how IBM (where Binnig and Rohrer first developed the STM) used an STM in combination with an iron atom to serve as an electron-spin resonance sensor to read the magnetic pole of holmium atoms. The north and south poles of the holmium atoms served as the 0 and 1 of digital logic.

The Canadian researchers have taken a somewhat different approach to making an STM into a data storage device by automating a known technique that uses the ultrasharp tip of the STM to apply a voltage pulse above an atom to remove individual hydrogen atoms from the surface of a silicon wafer. Once the atom has been removed, there is a vacancy on the surface. These vacancies can be patterned on the surface to create devices and memories.

If you have the time, I recommend reading Dexter’s posting as he provides clear explanations, additional insight into the work, and more historical detail.