These are two entirely different types of research but taken together they help build a picture about how the cells in our bodies function.

Cells and light

An April 30, 2018 news item on phys.org describes work on controlling biology with light,

Over the past five years, University of Chicago chemist Bozhi Tian has been figuring out how to control biology with light.

A longterm science goal is devices to serve as the interface between researcher and body—both as a way to understand how cells talk among each other and within themselves, and eventually, as a treatment for brain or nervous system disorders [emphasis mine] by stimulating nerves to fire or limbs to move. Silicon—a versatile, biocompatible material used in both solar panels and surgical implants—is a natural choice.

In a paper published April 30 in Nature Biomedical Engineering, Tian’s team laid out a system of design principles for working with silicon to control biology at three levels—from individual organelles inside cells to tissues to entire limbs. The group has demonstrated each in cells or mice models, including the first time anyone has used light to control behavior without genetic modification.

“We want this to serve as a map, where you can decide which problem you would like to study and immediately find the right material and method to address it,” said Tian, an assistant professor in the Department of Chemistry.

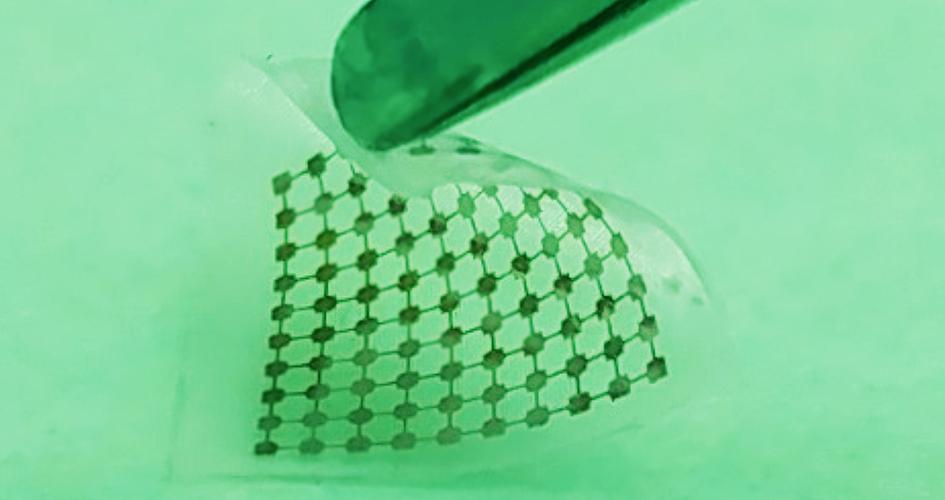

Researchers built this thin layer of silicon lace to modulate neural signals when activated by light. Courtesy of Yuanwen Jiang and Bozhi Tian

An April 30, 2018 University of Chicago news release by Louise Lerner, which originated the news item, describes the work in greater detail,

The scientists’ map lays out best methods to craft silicon devices depending on both the intended task and the scale—ranging from inside a cell to a whole animal.

For example, to affect individual brain cells, silicon can be crafted to respond to light by emitting a tiny ionic current, which encourages neurons to fire. But in order to stimulate limbs, scientists need a system whose signals can travel farther and are stronger—such as a gold-coated silicon material in which light triggers a chemical reaction.

The mechanical properties of the implant are important, too. Say researchers would like to work with a larger piece of the brain, like the cortex, to control motor movement. The brain is a soft, squishy substance, so they’ll need a material that’s similarly soft and flexible, but can bind tightly against the surface. They’d want thin and lacy silicon, say the design principles.

The team favors this method because it doesn’t require genetic modification or a power supply wired in, since the silicon can be fashioned into what are essentially tiny solar panels. (Many other forms of monitoring or interacting with the brain need to have a power supply, and keeping a wire running into a patient is an infection risk.)

They tested the concept in mice and found they could stimulate limb movements by shining light on brain implants. Previous research tested the concept in neurons.

“We don’t have answers to a number of intrinsic questions about biology, such as whether individual mitochondria communicate remotely through bioelectric signals,” said Yuanwen Jiang, the first author on the paper, then a graduate student at UChicago and now a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford. “This set of tools could address such questions as well as pointing the way to potential solutions for nervous system disorders.”

Other UChicago authors were Assoc. Profs. Chin-Tu Chen and Chien-Min Kao, Asst. Prof Xiaoyang, postdoctoral researchers Jaeseok Yi, Yin Fang, Xiang Gao, Jiping Yue, Hsiu-Ming Tsai, Bing Liu and Yin Fang, graduate students Kelliann Koehler, Vishnu Nair, and Edward Sudzilovsky, and undergraduate student George Freyermuth.

Other researchers on the paper hailed from Northwestern University, the University of Illinois at Chicago and Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

The researchers have also made this video illustrating their work,

via Gfycat Tiny silicon nanowires (in blue), activated by light, trigger activity in neurons. (Courtesy Yuanwen Jiang and Bozhi Tian)

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Rational design of silicon structures for optically controlled multiscale biointerfaces by Yuanwen Jiang, Xiaojian Li, Bing Liu, Jaeseok Yi, Yin Fang, Fengyuan Shi, Xiang Gao, Edward Sudzilovsky, Ramya Parameswaran, Kelliann Koehler, Vishnu Nair, Jiping Yue, KuangHua Guo, Yin Fang, Hsiu-Ming Tsai, George Freyermuth, Raymond C. S. Wong, Chien-Min Kao, Chin-Tu Chen, Alan W. Nicholls, Xiaoyang Wu, Gordon M. G. Shepherd, & Bozhi Tian. Nature Biomedical Engineering (2018) doi:10.1038/s41551-018-0230-1 Published: 30 April 2018

This paper is behind a paywall.

Mathematics and how living cells ‘think’

This May 2, 2018 Queensland University of Technology (QUT; Australia) press release is also on EurekAlert,

How does the ‘brain’ of a living cell work, allowing an organism to function and thrive in changing and unfavourable environments?

Queensland University of Technology (QUT) researcher Dr Robyn Araujo has developed new mathematics to solve a longstanding mystery of how the incredibly complex biological networks within cells can adapt and reset themselves after exposure to a new stimulus.

Her findings, published in Nature Communications, provide a new level of understanding of cellular communication and cellular ‘cognition’, and have potential application in a variety of areas, including new targeted cancer therapies and drug resistance.

Dr Araujo, a lecturer in applied and computational mathematics in QUT’s Science and Engineering Faculty, said that while we know a great deal about gene sequences, we have had extremely limited insight into how the proteins encoded by these genes work together as an integrated network – until now.

“Proteins form unfathomably complex networks of chemical reactions that allow cells to communicate and to ‘think’ – essentially giving the cell a ‘cognitive’ ability, or a ‘brain’,” she said. “It has been a longstanding mystery in science how this cellular ‘brain’ works.

“We could never hope to measure the full complexity of cellular networks – the networks are simply too large and interconnected and their component proteins are too variable.

“But mathematics provides a tool that allows us to explore how these networks might be constructed in order to perform as they do.

“My research is giving us a new way to look at unravelling network complexity in nature.”

Dr Araujo’s work has focused on the widely observed function called perfect adaptation – the ability of a network to reset itself after it has been exposed to a new stimulus.

“An example of perfect adaptation is our sense of smell,” she said. “When exposed to an odour we will smell it initially but after a while it seems to us that the odour has disappeared, even though the chemical, the stimulus, is still present.

“Our sense of smell has exhibited perfect adaptation. This process allows it to remain sensitive to further changes in our environment so that we can detect both very feint and very strong odours.

“This kind of adaptation is essentially what takes place inside living cells all the time. Cells are exposed to signals – hormones, growth factors, and other chemicals – and their proteins will tend to react and respond initially, but then settle down to pre-stimulus levels of activity even though the stimulus is still there.

“I studied all the possible ways a network can be constructed and found that to be capable of this perfect adaptation in a robust way, a network has to satisfy an extremely rigid set of mathematical principles. There are a surprisingly limited number of ways a network could be constructed to perform perfect adaptation.

“Essentially we are now discovering the needles in the haystack in terms of the network constructions that can actually exist in nature.

“It is early days, but this opens the door to being able to modify cell networks with drugs and do it in a more robust and rigorous way. Cancer therapy is a potential area of application, and insights into how proteins work at a cellular level is key.”

Dr Araujo said the published study was the result of more than “five years of relentless effort to solve this incredibly deep mathematical problem”. She began research in this field while at George Mason University in Virginia in the US.

Her mentor at the university’s College of Science and co-author of the Nature Communications paper, Professor Lance Liotta, said the “amazing and surprising” outcome of Dr Araujo’s study is applicable to any living organism or biochemical network of any size.

“The study is a wonderful example of how mathematics can have a profound impact on society and Dr Araujo’s results will provide a set of completely fresh approaches for scientists in a variety of fields,” he said.

“For example, in strategies to overcome cancer drug resistance – why do tumours frequently adapt and grow back after treatment?

“It could also help understanding of how our hormone system, our immune defences, perfectly adapt to frequent challenges and keep us well, and it has future implications for creating new hypotheses about drug addiction and brain neuron signalling adaptation.”

Hre’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

The topological requirements for robust perfect adaptation in networks of any size by Robyn P. Araujo & Lance A. Liotta. Nature Communicationsvolume 9, Article number: 1757 (2018) doi:10.1038/s41467-018-04151-6 Published: 01 May 2018

This paper is open access.