The National University of Singapore (NUS) and skyrmions are featured in an April 10, 2017 news item on phys.org,

A team of scientists led by Associate Professor Yang Hyunsoo from the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the National University of Singapore’s (NUS) Faculty of Engineering has invented a novel ultra-thin multilayer film which could harness the properties of tiny magnetic whirls, known as skyrmions, as information carriers for storing and processing data on magnetic media.

The nano-sized thin film, which was developed in collaboration with researchers from Brookhaven National Laboratory, Stony Brook University, and Louisiana State University, is a critical step towards the design of data storage devices that use less power and work faster than existing memory technologies. The invention was reported in prestigious scientific journal Nature Communications on 10 March 2017.

An April 10, 2017 NUS press release on EurekAlert, which originated the news item, describes the work in more detail,

Tiny magnetic whirls with huge potential as information carriers

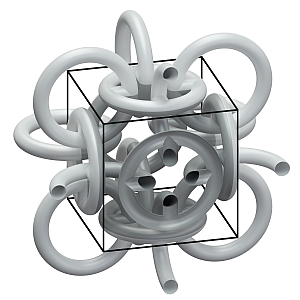

The digital transformation has resulted in ever-increasing demands for better processing and storing of large amounts of data, as well as improvements in hard drive technology. Since their discovery in magnetic materials in 2009, skyrmions, which are tiny swirling magnetic textures only a few nanometres in size, have been extensively studied as possible information carriers in next-generation data storage and logic devices.

Skyrmions have been shown to exist in layered systems, with a heavy metal placed beneath a ferromagnetic material. Due to the interaction between the different materials, an interfacial symmetry breaking interaction, known as the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI), is formed, and this helps to stabilise a skyrmion. However, without an out-of-plane magnetic field present, the stability of the skyrmion is compromised. In addition, due to its tiny size, it is difficult to image the nano-sized materials.

To address these limitations, the researchers worked towards creating stable magnetic skyrmions at room temperature without the need for a biasing magnetic field.

Unique material for data storage

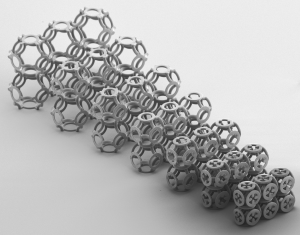

The NUS team, which also comprises Dr Shawn Pollard and Ms Yu Jiawei from the NUS Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, found that a large DMI could be maintained in multilayer films composed of cobalt and palladium, and this is large enough to stabilise skyrmion spin textures.

In order to image the magnetic structure of these films, the NUS researchers, in collaboration with Brookhaven National Laboratory in the United States, employed Lorentz transmission electron microscopy (L-TEM). L-TEM has the ability to image magnetic structures below 10 nanometres, but it has not been used to observe skyrmions in multilayer geometries previously as it was predicted to exhibit zero signal. However, when conducting the experiments, the researchers found that by tilting the films with respect to the electron beam, they found that they could obtain clear contrast consistent with that expected for skyrmions, with sizes below 100 nanometres.

Dr Pollard explained, “It has long been assumed that there is no DMI in a symmetric structure like the one present in our work, hence, there will be no skyrmion. It is really unexpected for us to find both large DMI and skyrmions in the multilayer film we engineered. What’s more, these nanoscale skyrmions persisted even after the removal of an external biasing magnetic field, which are the first of their kind.”

Assoc Prof Yang added, “This experiment not only demonstrates the usefulness of L-TEM in studying these systems, but also opens up a completely new material in which skyrmions can be created. Without the need for a biasing field, the design and implementation of skyrmion based devices are significantly simplified. The small size of the skyrmions, combined with the incredible stability generated here, could be potentially useful for the design of next-generation spintronic devices that are energy efficient and can outperform current memory technologies.”

Next step

Assoc Prof Yang and his team are currently looking at how nanoscale skyrmions interact with each other and with electrical currents, to further the development of skyrmion based electronics.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Observation of stable Néel skyrmions in cobalt/palladium multilayers with Lorentz transmission electron microscopy by Shawn D. Pollard, Joseph A. Garlow, Jiawei Yu, Zhen Wang, Yimei Zhu & Hyunsoo Yang. Nature Communications 8, Article number: 14761 (2017) doi:10.1038/ncomms14761 Published online: 10 March 2017

This is an open access paper.