I have two news bits about graphene and magnetism. If I understood what I was reading, one is more focused on applications and the other is focused on further establishing the field of valleytronics.

University of Cambridge and superconductivity

A February 8, 2021 news item on Nanowerk announces ‘magnetic work’ from the University of Cambridge (Note: A link has been removed),

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge, were able to control the conductivity and magnetism of iron thiophosphate (FePS3), a two-dimensional material which undergoes a transition from an insulator to a metal when compressed. This class of magnetic materials offers new routes to understanding the physics of new magnetic states and superconductivity.

Using new high-pressure techniques, the researchers have shown what happens to magnetic graphene during the transition from insulator to conductor and into its unconventional metallic state, realised only under ultra-high pressure conditions. When the material becomes metallic, it remains magnetic, which is contrary to previous results and provides clues as to how the electrical conduction in the metallic phase works. The newly discovered high-pressure magnetic phase likely forms a precursor to superconductivity so understanding its mechanisms is vital.

Their results, published in the journal Physical Review X, also suggest a way that new materials could be engineered to have combined conduction and magnetic properties, which could be useful in the development of new technologies such as spintronics, which could transform the way in which computers process information.

…

A February 8, 2021 University of Cambridge press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves into the topic,

Properties of matter can alter dramatically with changing dimensionality. For example, graphene, carbon nanotubes, graphite and diamond are all made of carbon atoms, but have very different properties due to their different structure and dimensionality.

“But imagine if you were also able to change all of these properties by adding magnetism,” said first author Dr Matthew Coak, who is jointly based at Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and the University of Warwick. “A material which could be mechanically flexible and form a new kind of circuit to store information and perform computation. This is why these materials are so interesting, and because they drastically change their properties when put under pressure so we can control their behaviour.”

In a previous study by Sebastian Haines of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and the Department of Earth Sciences, researchers established that the material becomes a metal at high pressure, and outlined how the crystal structure and arrangement of atoms in the layers of this 2D material change through the transition.

“The missing piece has remained however, the magnetism,” said Coak. “With no experimental techniques able to probe the signatures of magnetism in this material at pressures this high, our international team had to develop and test our own new techniques to make it possible.”

The researchers used new techniques to measure the magnetic structure up to record-breaking high pressures, using specially designed diamond anvils and neutrons to act as the probe of magnetism. They were then able to follow the evolution of the magnetism into the metallic state.

“To our surprise, we found that the magnetism survives and is in some ways strengthened,” co-author Dr Siddharth Saxena, group leader at the Cavendish Laboratory. “This is unexpected, as the newly-freely-roaming electrons in a newly conducting material can no longer be locked to their parent iron atoms, generating magnetic moments there – unless the conduction is coming from an unexpected source.”

In their previous paper, the researchers showed these electrons were ‘frozen’ in a sense. But when they made them flow or move, they started interacting more and more. The magnetism survives, but gets modified into new forms, giving rise to new quantum properties in a new type of magnetic metal.

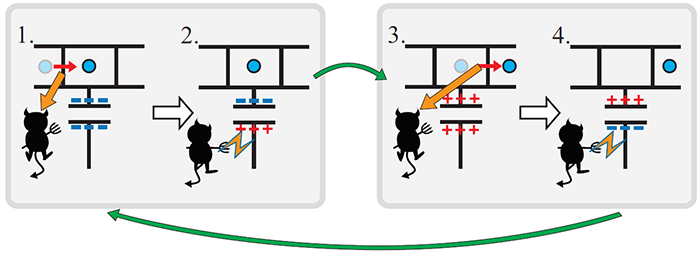

How a material behaves, whether conductor or insulator, is mostly based on how the electrons, or charge, move around. However, the ‘spin’ of the electrons has been shown to be the source of magnetism. Spin makes electrons behave a bit like tiny bar magnets and point a certain way. Magnetism from the arrangement of electron spins is used in most memory devices: harnessing and controlling it is important for developing new technologies such as spintronics, which could transform the way in which computers process information.

“The combination of the two, the charge and the spin, is key to how this material behaves,” said co-author Dr David Jarvis from the Institut Laue-Langevin, France, who carried out this work as the basis of his PhD studies at the Cavendish Laboratory. “Finding this sort of quantum multi-functionality is another leap forward in the study of these materials.”

“We don’t know exactly what’s happening at the quantum level, but at the same time, we can manipulate it,” said Saxena. “It’s like those famous ‘unknown unknowns’: we’ve opened up a new door to properties of quantum information, but we don’t yet know what those properties might be.”

There are more potential chemical compounds to synthesise than could ever be fully explored and characterised. But by carefully selecting and tuning materials with special properties, it is possible to show the way towards the creation of compounds and systems, but without having to apply huge amounts of pressure.

Additionally, gaining fundamental understanding of phenomena such as low-dimensional magnetism and superconductivity allows researchers to make the next leaps in materials science and engineering, with particular potential in energy efficiency, generation and storage.

As for the case of magnetic graphene, the researchers next plan to continue the search for superconductivity within this unique material. “Now that we have some idea what happens to this material at high pressure, we can make some predictions about what might happen if we try to tune its properties through adding free electrons by compressing it further,” said Coak.

“The thing we’re chasing is superconductivity,” said Saxena. “If we can find a type of superconductivity that’s related to magnetism in a two-dimensional material, it could give us a shot at solving a problem that’s gone back decades.”

The citation and link to the paper are at the end of this blog posting.

Aalto University’s valleytronics

Further north in Finland, researchers at Aalto University make some advances applicable to the field of valleytronics, from a February 5, 2021 Aalto University press release (also on EurekAltert but published February 8, 2021),

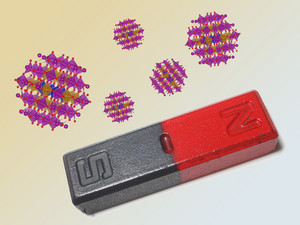

Electrons in materials have a property known as ‘spin’, which is responsible for a variety of properties, the most well-known of which is magnetism. Permanent magnets, like the ones used for refrigerator doors, have all the spins in their electrons aligned in the same direction. Scientists refer to this behaviour as ferromagnetism, and the research field of trying to manipulate spin as spintronics.

Down in the quantum world, spins can arrange in more exotic ways, giving rise to frustrated states and entangled magnets. Interestingly, a property similar to spin, known as “the valley,” appears in graphene materials. This unique feature has given rise to the field of valleytronics, which aims to exploit the valley property for emergent physics and information processing, very much like spintronics relies on pure spin physics.

‘Valleytronics would potentially allow encoding information in the quantum valley degree of freedom, similar to how electronics do it with charge and spintronics with the spin.’ Explains Professor Jose Lado, from Aalto’s Department of applied physics, and one of the authors of the work. ‘What’s more, valleytronic devices would offer a dramatic increase in the processing speeds in comparison with electronics, and with much higher stability towards magnetic field noise in comparison with spintronic devices.’

Structures made of rotated, ultra-thin materials provide a rich solid-state platform for designing novel devices. In particular, slightly twisted graphene layers have recently been shown to have exciting unconventional properties, that can ultimately lead to a new family of materials for quantum technologies. These unconventional states which are already being explored depend on electrical charge or spin. The open question is if the valley can also lead to its own family of exciting states.

Making materials for valleytronics

For this goal, it turns out that conventional ferromagnets play a vital role, pushing graphene to the realms of valley physics. In a recent work, Ph.D. student Tobias Wolf, together with Profs. Oded Zilberberg and Gianni Blatter at ETH Zurich, and Prof. Jose Lado at Aalto University, showed a new direction for correlated physics in magnetic van der Waals materials.

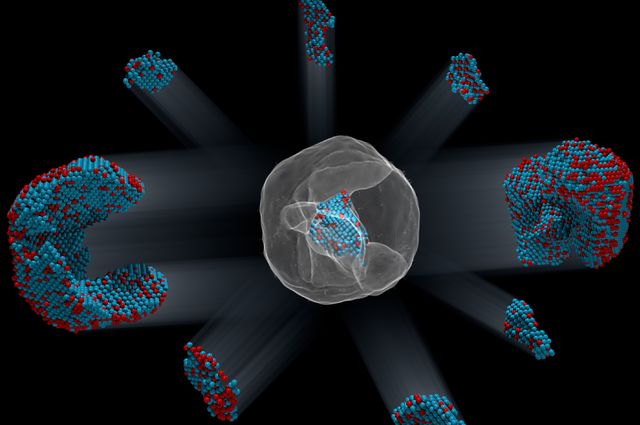

The team showed that sandwiching two slightly rotated layers of graphene between a ferromagnetic insulator provides a unique setting for new electronic states. The combination of ferromagnets, graphene’s twist engineering, and relativistic effects force the “valley” property to dominate the electrons behaviour in the material. In particular, the researchers showed how these valley-only states can be tuned electrically, providing a materials platform in which valley-only states can be generated. Building on top of the recent breakthrough in spintronics and van der Waals materials, valley physics in magnetic twisted van der Waals multilayers opens the door to the new realm of correlated twisted valleytronics.

‘Demonstrating these states represents the starting point towards new exotic entangled valley states.’ Said Professor Lado, ‘Ultimately, engineering these valley states can allow realizing quantum entangled valley liquids and fractional quantum valley Hall states. These two exotic states of matter have not been found in nature yet, and would open exciting possibilities towards a potentially new graphene-based platform for topological quantum computing.’

Citations and links

Here’s a link to and a citation for the University of Cambridge research,

Emergent Magnetic Phases in Pressure-Tuned van der Waals Antiferromagnet FePS3 by Matthew J. Coak, David M. Jarvis, Hayrullo Hamidov, Andrew R. Wildes, Joseph A. M. Paddison, Cheng Liu, Charles R. S. Haines, Ngoc T. Dang, Sergey E. Kichanov, Boris N. Savenko, Sungmin Lee, Marie Kratochvílová, Stefan Klotz, Thomas C. Hansen, Denis P. Kozlenko, Je-Geun Park, and Siddharth S. Saxena. Phys. Rev. X 11, 011024 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.11.011024 Published 5 February 2021

This article appears to be open access.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the Aalto University research,

Spontaneous Valley Spirals in Magnetically Encapsulated Twisted Bilayer Graphene by Tobias M. R. Wolf, Oded Zilberberg, Gianni Blatter, and Jose L. Lado. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 056803 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.126.056803 Published 4 February 2021

This paper is behind a paywall.

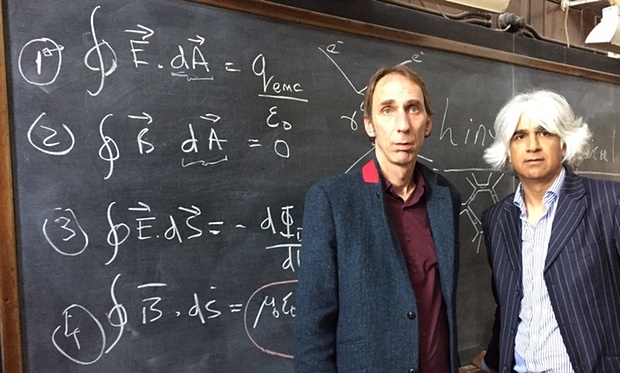

![Original manuscript of Maxwell’s seminal paper Photograph: Jon Butterworth/Royal Society [downloaded from http://www.theguardian.com/science/life-and-physics/2015/nov/22/maxwells-equations-150-years-of-light]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/MaxwellsUnificationTheory.jpg)