An April 18, 2018 news item on phys.org highlights an exciting graphene development at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT),

MIT engineers have developed a continuous manufacturing process that produces long strips of high-quality graphene.

The team’s results are the first demonstration of an industrial, scalable method for manufacturing high-quality graphene that is tailored for use in membranes that filter a variety of molecules, including salts, larger ions, proteins, or nanoparticles. Such membranes should be useful for desalination, biological separation, and other applications.

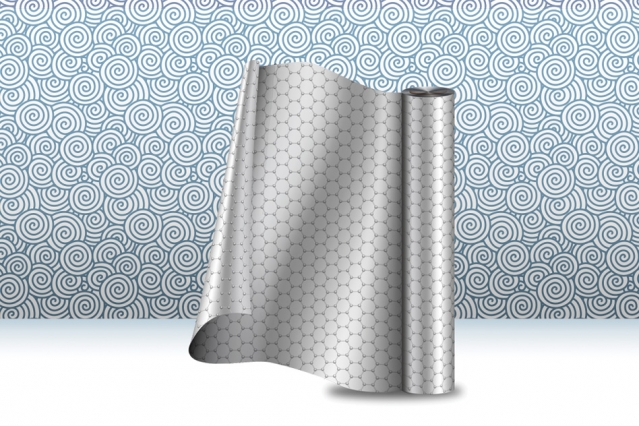

A new manufacturing process produces strips of graphene, at large scale, for use in membrane technologies and other applications. Image: Christine Daniloff, MIT

An April 17, 2018 MIT news release (also on EurekAlert) by Jennifer Chu, which originated the news item,. provides more detail,

“For several years, researchers have thought of graphene as a potential route to ultrathin membranes,” says John Hart, associate professor of mechanical engineering and director of the Laboratory for Manufacturing and Productivity at MIT. “We believe this is the first study that has tailored the manufacturing of graphene toward membrane applications, which require the graphene to be seamless, cover the substrate fully, and be of high quality.”

Hart is the senior author on the paper, which appears online in the journal Applied Materials and Interfaces. The study includes first author Piran Kidambi, a former MIT postdoc who is now an assistant professor at Vanderbilt University; MIT graduate students Dhanushkodi Mariappan and Nicholas Dee; Sui Zhang of the National University of Singapore; Andrey Vyatskikh, a former student at the Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology who is now at Caltech; and Rohit Karnik, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at MIT.

Growing graphene

For many researchers, graphene is ideal for use in filtration membranes. A single sheet of graphene resembles atomically thin chicken wire and is composed of carbon atoms joined in a pattern that makes the material extremely tough and impervious to even the smallest atom, helium.

Researchers, including Karnik’s group, have developed techniques to fabricate graphene membranes and precisely riddle them with tiny holes, or nanopores, the size of which can be tailored to filter out specific molecules. For the most part, scientists synthesize graphene through a process called chemical vapor deposition, in which they first heat a sample of copper foil and then deposit onto it a combination of carbon and other gases.

Graphene-based membranes have mostly been made in small batches in the laboratory, where researchers can carefully control the material’s growth conditions. However, Hart and his colleagues believe that if graphene membranes are ever to be used commercially they will have to be produced in large quantities, at high rates, and with reliable performance.

“We know that for industrialization, it would need to be a continuous process,” Hart says. “You would never be able to make enough by making just pieces. And membranes that are used commercially need to be fairly big – some so big that you would have to send a poster-wide sheet of foil into a furnace to make a membrane.”

A factory roll-out

The researchers set out to build an end-to-end, start-to-finish manufacturing process to make membrane-quality graphene.

The team’s setup combines a roll-to-roll approach – a common industrial approach for continuous processing of thin foils – with the common graphene-fabrication technique of chemical vapor deposition, to manufacture high-quality graphene in large quantities and at a high rate. The system consists of two spools, connected by a conveyor belt that runs through a small furnace. The first spool unfurls a long strip of copper foil, less than 1 centimeter wide. When it enters the furnace, the foil is fed through first one tube and then another, in a “split-zone” design.

While the foil rolls through the first tube, it heats up to a certain ideal temperature, at which point it is ready to roll through the second tube, where the scientists pump in a specified ratio of methane and hydrogen gas, which are deposited onto the heated foil to produce graphene.

“Graphene starts forming in little islands, and then those islands grow together to form a continuous sheet,” Hart says. “By the time it’s out of the oven, the graphene should be fully covering the foil in one layer, kind of like a continuous bed of pizza.”

As the graphene exits the furnace, it’s rolled onto the second spool. The researchers found that they were able to feed the foil continuously through the system, producing high-quality graphene at a rate of 5 centimers per minute. Their longest run lasted almost four hours, during which they produced about 10 meters of continuous graphene.

“If this were in a factory, it would be running 24-7,” Hart says. “You would have big spools of foil feeding through, like a printing press.”

Flexible design

Once the researchers produced graphene using their roll-to-roll method, they unwound the foil from the second spool and cut small samples out. They cast the samples with a polymer mesh, or support, using a method developed by scientists at Harvard University, and subsequently etched away the underlying copper.

“If you don’t support graphene adequately, it will just curl up on itself,” Kidambi says. “So you etch copper out from underneath and have graphene directly supported by a porous polymer – which is basically a membrane.”

The polymer covering contains holes that are larger than graphene’s pores, which Hart says act as microscopic “drumheads,” keeping the graphene sturdy and its tiny pores open.

The researchers performed diffusion tests with the graphene membranes, flowing a solution of water, salts, and other molecules across each membrane. They found that overall, the membranes were able to withstand the flow while filtering out molecules. Their performance was comparable to graphene membranes made using conventional, small-batch approaches.

The team also ran the process at different speeds, with different ratios of methane and hydrogen gas, and characterized the quality of the resulting graphene after each run. They drew up plots to show the relationship between graphene’s quality and the speed and gas ratios of the manufacturing process. Kidambi says that if other designers can build similar setups, they can use the team’s plots to identify the settings they would need to produce a certain quality of graphene.

“The system gives you a great degree of flexibility in terms of what you’d like to tune graphene for, all the way from electronic to membrane applications,” Kidambi says.

Looking forward, Hart says he would like to find ways to include polymer casting and other steps that currently are performed by hand, in the roll-to-roll system.

“In the end-to-end process, we would need to integrate more operations into the manufacturing line,” Hart says. “For now, we’ve demonstrated that this process can be scaled up, and we hope this increases confidence and interest in graphene-based membrane technologies, and provides a pathway to commercialization.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A Scalable Route to Nanoporous Large-Area Atomically Thin Graphene Membranes by Roll-to-Roll Chemical Vapor Deposition and Polymer Support Casting by Piran R. Kidambi, Dhanushkodi D. Mariappan, Nicholas T. Dee, Andrey Vyatskikh, Sui Zhang, Rohit Karnik, and A. John Hart. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces, 2018, 10 (12), pp 10369–10378 DOI: 10.1021/acsami.8b00846 Publication Date (Web): March 19, 2018

Copyright © 2018 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

Finally, there is a video of the ‘graphene spooling out’ process,