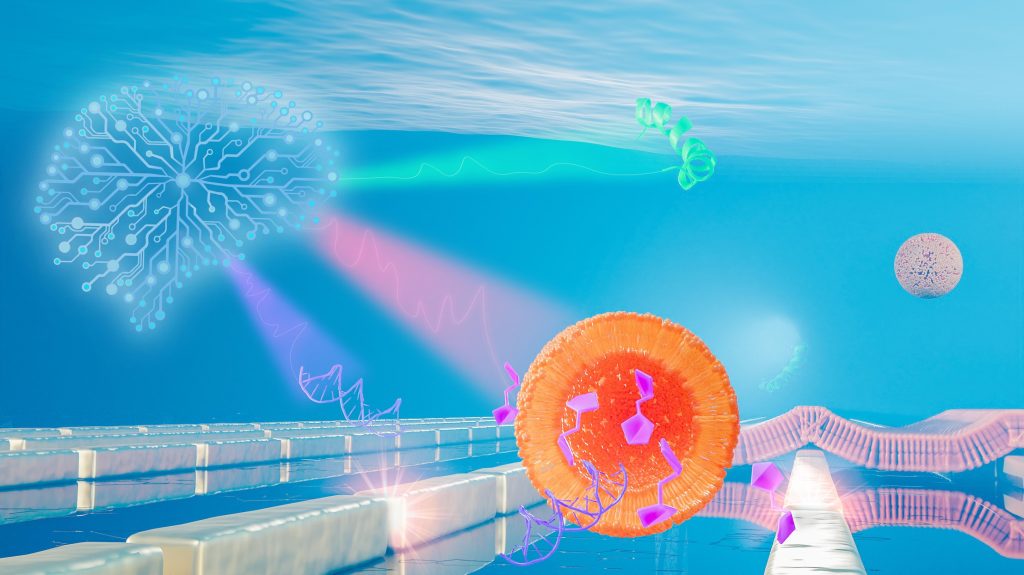

If you look at the big orange dot (representing the nanosensors?), you’ll see those purplish/fuschia objects resemble musical notes (biological molecules?). I think that brainlike object to the left and in light blue is the artificial intelligence (AI) component. (If anyone wants to correct my guesses or identify the bits I can’t, please feel free to add to the Comments for this blog.)

Getting back to my topic, keep the ‘musical notes’ in mind as you read about some of the latest research from l’École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) in an April 7, 2021 news item on Nanowerk,

The tiny world of biomolecules is rich in fascinating interactions between a plethora of different agents such as intricate nanomachines (proteins), shape-shifting vessels (lipid complexes), chains of vital information (DNA) and energy fuel (carbohydrates). Yet the ways in which biomolecules meet and interact to define the symphony of life is exceedingly complex.

Scientists at the Bionanophotonic Systems Laboratory in EPFL’s School of Engineering have now developed a new biosensor that can be used to observe all major biomolecule classes of the nanoworld without disturbing them. Their innovative technique uses nanotechnology, metasurfaces, infrared light and artificial intelligence.

To each molecule its own melody

In this nano-sized symphony, perfect orchestration makes physiological wonders such as vision and taste possible, while slight dissonances can amplify into horrendous cacophonies leading to pathologies such as cancer and neurodegeneration.

…

An April 7, 2021 EPFL press release, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

“Tuning into this tiny world and being able to differentiate between proteins, lipids, nucleic acids and carbohydrates without disturbing their interactions is of fundamental importance for understanding life processes and disease mechanisms,” says Hatice Altug, the head of the Bionanophotonic Systems Laboratory.

Light, and more specifically infrared light, is at the core of the biosensor developed by Altug’s team. Humans cannot see infrared light, which is beyond the visible light spectrum that ranges from blue to red. However, we can feel it in the form of heat in our bodies, as our molecules vibrate under the infrared light excitation.

Molecules consist of atoms bonded to each other and – depending on the mass of the atoms and the arrangement and stiffness of their bonds – vibrate at specific frequencies. This is similar to the strings on a musical instrument that vibrate at specific frequencies depending on their length. These resonant frequencies are molecule-specific, and they mostly occur in the infrared frequency range of the electromagnetic spectrum.

“If you imagine audio frequencies instead of infrared frequencies, it’s as if each molecule has its own characteristic melody,” says Aurélian John-Herpin, a doctoral assistant at Altug’s lab and the first author of the publication. “However, tuning into these melodies is very challenging because without amplification, they are mere whispers in a sea of sounds. To make matters worse, their melodies can present very similar motifs making it hard to tell them apart.”

Metasurfaces and artificial intelligence

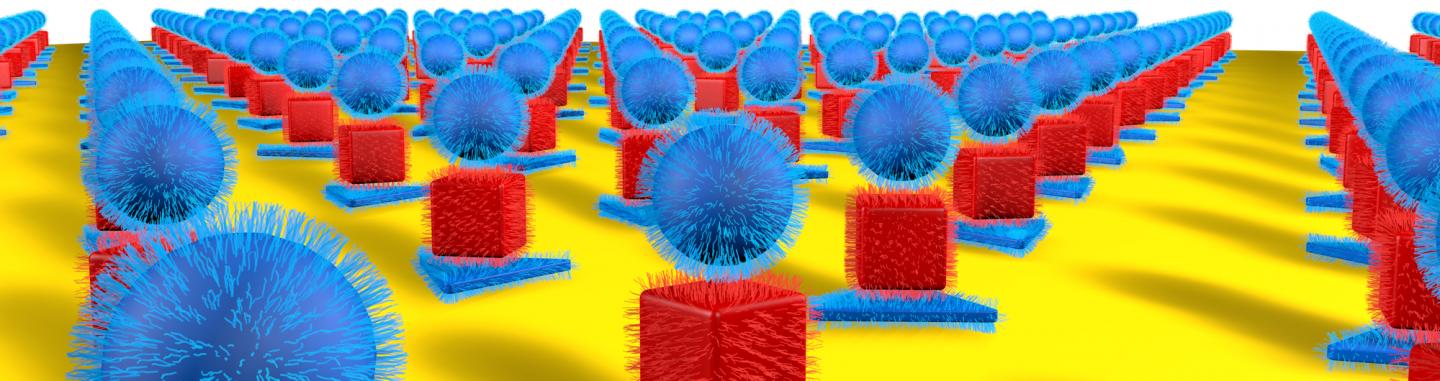

The scientists solved these two issues using metasurfaces and AI. Metasurfaces are man-made materials with outstanding light manipulation capabilities at the nano scale, thereby enabling functions beyond what is otherwise seen in nature. Here, their precisely engineered meta-atoms made out of gold nanorods act like amplifiers of light-matter interactions by tapping into the plasmonic excitations resulting from the collective oscillations of free electrons in metals. “In our analogy, these enhanced interactions make the whispered molecule melodies more audible,” says John-Herpin.

AI is a powerful tool that can be fed with more data than humans can handle in the same amount of time and that can quickly develop the ability to recognize complex patterns from the data. John-Herpin explains, “AI can be imagined as a complete beginner musician who listens to the different amplified melodies and develops a perfect ear after just a few minutes and can tell the melodies apart, even when they are played together – like in an orchestra featuring many instruments simultaneously.”

The first biosensor of its kind

When the scientists’ infrared metasurfaces are augmented with AI, the new sensor can be used to analyze biological assays featuring multiple analytes simultaneously from the major biomolecule classes and resolving their dynamic interactions.

“We looked in particular at lipid vesicle-based nanoparticles and monitored their breakage through the insertion of a toxin peptide and the subsequent release of vesicle cargos of nucleotides and carbohydrates, as well as the formation of supported lipid bilayer patches on the metasurface,” says Altug.

This pioneering AI-powered, metasurface-based biosensor will open up exciting perspectives for studying and unraveling inherently complex biological processes, such as intercellular communication via exosomesand the interaction of nucleic acids and carbohydrates with proteins in gene regulation and neurodegeneration.

“We imagine that our technology will have applications in the fields of biology, bioanalytics and pharmacology – from fundamental research and disease diagnostics to drug development,” says Altug.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Infrared Metasurface Augmented by Deep Learning for Monitoring Dynamics between All Major Classes of Biomolecules by Aurelian John‐Herpin, Deepthy Kavungal. Lea von Mücke, Hatice Altug. Advanced Materials Volume 33, Issue 14 April 8, 2021 2006054 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202006054 First published: 22 February 2021

This paper is open access.