Today’s live salmon may sport a battery for monitoring purposes and now scientists have developed one that is significantly more powerful according to a Feb. 17, 2014 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) news release (dated Feb. 18, 2014 on EurekAlert),

Scientists have created a microbattery that packs twice the energy compared to current microbatteries used to monitor the movements of salmon through rivers in the Pacific Northwest and around the world.

The battery, a cylinder just slightly larger than a long grain of rice, is certainly not the world’s smallest battery, as engineers have created batteries far tinier than the width of a human hair. But those smaller batteries don’t hold enough energy to power acoustic fish tags. The new battery is small enough to be injected into an organism and holds much more energy than similar-sized batteries.

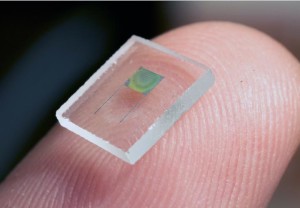

Here’s a photo of the battery as it rests amongst grains of rice,

The microbattery created by Jie Xiao and Daniel Deng and colleagues, amid grains of rice. Courtesy PNNL

The news release goes on to explain why scientists are developing a lighter battery for salmon and how they achieved their goal,

For scientists tracking the movements of salmon, the lighter battery translates to a smaller transmitter which can be inserted into younger, smaller fish. That would allow scientists to track their welfare earlier in the life cycle, oftentimes in the small streams that are crucial to their beginnings. The new battery also can power signals over longer distances, allowing researchers to track fish further from shore or from dams, or deeper in the water.

“The invention of this battery essentially revolutionizes the biotelemetry world and opens up the study of earlier life stages of salmon in ways that have not been possible before,” said M. Brad Eppard, a fisheries biologist with the Portland District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

“For years the chief limiting factor to creating a smaller transmitter has been the battery size. That hurdle has now been overcome,” added Eppard, who manages the Portland District’s fisheries research program.

The Corps and other agencies use the information from tags to chart the welfare of endangered fish and to help determine the optimal manner to operate dams. Three years ago the Corps turned to Z. Daniel Deng, a PNNL engineer, to create a smaller transmitter, one small enough to be injected, instead of surgically implanted, into fish. Injection is much less invasive and stressful for the fish, and it’s a faster and less costly process.

“This was a major challenge which really consumed us these last three years,” said Deng. “There’s nothing like this available commercially, that can be injected. Either the batteries are too big, or they don’t last long enough to be useful. That’s why we had to design our own.”

Deng turned to materials science expert Jie Xiao to create the new battery design.

To pack more energy into a small area, Xiao’s team improved upon the “jellyroll” technique commonly used to make larger household cylindrical batteries. Xiao’s team laid down layers of the battery materials one on top of the other in a process known as lamination, then rolled them up together, similar to how a jellyroll is created. The layers include a separating material sandwiched by a cathode made of carbon fluoride and an anode made of lithium.

The technique allowed her team to increase the area of the electrodes without increasing their thickness or the overall size of the battery. The increased area addresses one of the chief problems when making such a small battery — keeping the impedance, which is a lot like resistance, from getting too high. High impedance occurs when so many electrons are packed into a small place that they don’t flow easily or quickly along the routes required in a battery, instead getting in each other’s way. The smaller the battery, the bigger the problem.

Using the jellyroll technique allowed Xiao’s team to create a larger area for the electrons to interact, reducing impedance so much that the capacity of the material is about double that of traditional microbatteries used in acoustic fish tags.

“It’s a bit like flattening wads of Play-Doh, one layer at a time, and then rolling them up together, like a jelly roll,” says Xiao. “This allows you to pack more of your active materials into a small space without increasing the resistance.”

The new battery is a little more than half the weight of batteries currently used in acoustic fish tags — just 70 milligrams, compared to about 135 milligrams — and measures six millimeters long by three millimeters wide. The battery has an energy density of about 240 watt hours per kilogram, compared to around 100 for commercially available silver oxide button microbatteries.

The battery holds enough energy to send out an acoustic signal strong enough to be useful for fish-tracking studies even in noisy environments such as near large dams. The battery can power a 744-microsecond signal sent every three seconds for about three weeks, or about every five seconds for a month. It’s the smallest battery the researchers know of with enough energy capacity to maintain that level of signaling.

The batteries also work better in cold water where salmon often live, sending clearer signals at low temperatures compared to current batteries. That’s because their active ingredients are lithium and carbon fluoride, a chemistry that is promising for other applications but has not been common for microbatteries.

Last summer in Xiao’s laboratory, scientists Samuel Cartmell and Terence Lozano made by hand more than 1,000 of the rice-sized batteries. It’s a painstaking process, cutting and forming tiny snippets of sophisticated materials, putting them through a flattening device that resembles a pasta maker, binding them together, and rolling them by hand into tiny capsules. Their skilled hands rival those of surgeons, working not with tissue but with sensitive electronic materials.

A PNNL team led by Deng surgically implanted 700 of the tags into salmon in a field trial in the Snake River last summer. Preliminary results show that the tags performed extremely well. The results of that study and more details about the smaller, enhanced fish tags equipped with the new microbattery will come out in a forthcoming publication. Battelle, which operates PNNL, has applied for a patent on the technology.

I notice that while the second paragraph of the news release (in the first excerpt) says the battery is injectable, the final paragraph (in the second excerpt) says the team “surgically implanted” the tags with their new batteries into the salmon.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the newly published article in Scientific Reports,

Micro-battery Development for Juvenile Salmon Acoustic Telemetry System Applications by Honghao Chen, Samuel Cartmell, Qiang Wang, Terence Lozano, Z. Daniel Deng, Huidong Li, Xilin Chen, Yong Yuan, Mark E. Gross, Thomas J. Carlson, & Jie Xiao. Scientific Reports 4, Article number: 3790 doi:10.1038/srep03790 Published 21 January 2014

This paper is open access.

* I changed the headline from ‘Injectable batteries for live salmon made more powerful’ to ‘Injectable and more powerful batteries for live salmon’ to better reflect the information in the news release. Feb. 19, 2014 at 11:43 am PST.

ETA Feb. 20, 2014: Dexter Johnson has weighed in on this very engaging and practical piece of research in a Feb. 19, 2014 posting on his Nanoclast blog (on the IEEE [Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers]) website (Note: Links have been removed),

There’s no denying that building the world’s smallest battery is a notable achievement. But while they may lay the groundwork for future battery technologies, today such microbatteries are mostly laboratory curiosities.

Developing a battery that’s no bigger than a grain of rice—and that’s actually useful in the real world—is quite another kind of achievement. Researchers at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) have done just that, creating a battery based on graphene that has successfully been used in monitoring the movements of salmon through rivers.

The microbattery is being heralded as a breakthrough in biotelemetry and should give researchers never before insights into the movements and the early stages of life of the fish.

The battery is partly made from a fluorinated graphene that was described last year …