A January 26, 2023 University of Toronto news release (also found on EurekAlert and here but published on January 30, 2023) by Safa Jinje announced a coating the minimizes the amount of microplastic entering the water when your clothes are washed, Note: Links have been removed,

A team of University of Toronto Engineering researchers, led by Professor Kevin Golovin, have designed a solution to reduce the amount of microplastic fibres that are shed when clothes made of synthetic fabrics are washed.

In a world swamped by fast fashion — an industry that produces a high-volume of cheaply made clothing at an immense cost to the environment — more than two-thirds of clothes are now made of synthetic fabrics.

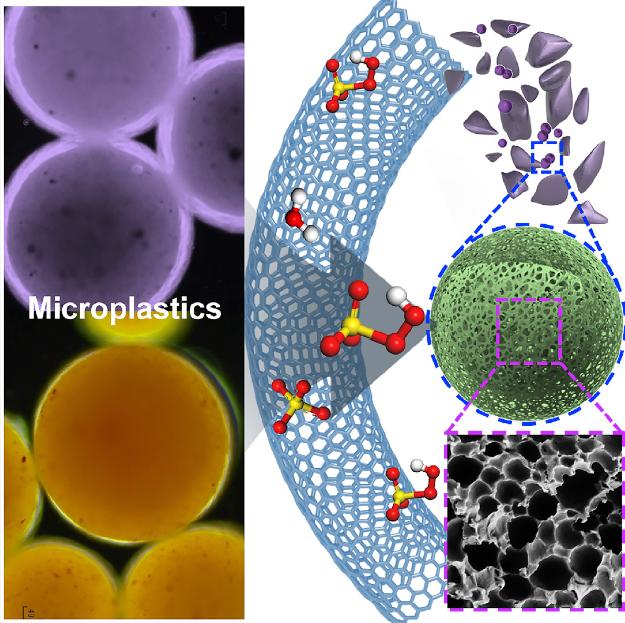

When clothes made from synthetic fabrics, such as nylon, polyester, acrylic and rayon, are washed in washing machines, the friction caused by cleaning cycles produces tiny tears in the fabric. These tears in turn cause microplastic fibres measuring less than 500 micrometres in length to break off and make their way down laundry drains to enter waterways.

Once microplastics end up in oceans and freshwater lakes and rivers, the particles are difficult to remove and will take decades or more to fully break down. The accumulation of this debris in bodies of water can threaten marine life. It can also become part of the human food chain through its presence in food and tap water, with effects on human health that are not yet clear.

Governments around the world have been looking for ways to minimize the pollution that comes from washing synthetic fabrics. One example is washing machine filters, which have emerged as a leading fix to stop microplastic fibres from entering waterways. In Ontario, legislative members have introduced a bill that would require filters in new washing machines in the province.

“And yet, when we look at what governments around the world are doing, there is no trend towards preventing the creation of microplastic fibres in the first place,” says Golovin.

“Our research is pushing in a different direction, where we actually solve the problem rather than putting a Band-Aid on the issue.”

Golovin and his team have created a two-layer coating made of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) brushes, which are linear, single polymer chains grown from a substrate to form a nanoscale surface layer.

Experiments conducted by the team showed that this coating can significantly reduce microfibre shedding of nylon clothing after repeated laundering. The researchers share their findings in a new paper published in Nature Sustainability.

“My lab has been working with this coating on other surfaces, including glass and metals, for a few years now,” says Golovin. “One of the properties we have observed is that it is quite slippery, meaning it has very low friction.”

PDMS is a silicon-based organic polymer that is found in many household products. Its presence in shampoos makes hair shiny and slippery. It is also used as a food additive in oils to prevent liquids from foaming when bottled.

Dr. Sudip Kumar Lahiri, a postdoctoral researcher in Golovin’s lab and lead author of the study, had the idea that if they could reduce the friction that occurs during wash cycles with a PDMS-based fabric finish, then that could stop fibres from rubbing together and breaking off during laundering.

One of the biggest challenges the researchers faced during their study was ensuring the PDMS brushes stayed on the fabric. Lahiri, who is a textile engineer by trade, developed a molecular primer based on his understanding of fabric dyes.

Lahiri reasoned that the type of bonding responsible for keeping dyed apparel colourful after repeated washes could work for the PDMS coating as well.

Neither the primer nor the PDMS brushes work separately to decrease the microplastic-fibre shedding. But together, they created a strong finish that reduced the release of microfibres by more than 90% after nine washes.

“PDMS brushes are environmentally friendly because they are not derived from petroleum like many polymers used today,” says Golovin, who was awarded a Connaught New Researcher award for this work.

“With the addition of Sudip’s primer, our coating is robust enough to remain on the garment and continue to reduce micro-fibre shedding over time.”

Since PDMS is naturally a hydrophobic (water-repellent) material, the researchers are currently working on making the coating hydrophilic, so that coated fabrics will be better able to wick away sweat. The team has also expanded the research to look beyond nylon fabrics, including polyester and synthetic-fabric blends.

“Many textiles are made of multiple types of fibres,” says Golovin. “We are working to formulate the correct polymer architecture so that our coating can durably adhere to all of those fibres simultaneously.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Polydimethylsiloxane-coated textiles with minimized microplastic pollution by Sudip Kumar Lahiri, Zahra Azimi Dijvejin & Kevin Golovin. Nature Sustainability (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-022-01059-4 Published: 26 January 2023

This paper is behind a paywall.