Institutions from Spain, Germany, and England collaborated on the study announced in this June 23, 2023 news item on Nanowerk, Note: A link has been removed,

For the last 20 years, scientists have been puzzled by how water behaves near carbon surfaces. It may flow much faster than expected from conventional flow theories or form strange arrangements such as square ice.

Now, an international team of researchers from the Max Plank Institute for Polymer Research of Mainz (Germany), the Catalan Institute of Nanoscience and Nanotechnology (ICN2, Spain), and the University of Manchester (England), reports in a study published in Nature Nanotechnology (“Electron cooling in graphene enhanced by plasmon–hydron resonance”) that water can interact directly with the carbon’s electrons: a quantum phenomenon that is very unusual in fluid dynamics.

…

There are two press releases with almost identical text, the June 22, 2023 Max Planck Institute press release with its additional introductory paragraph is below,

Water and carbon make a quantum couple: the flow of water on a carbon surface is governed by an unusual phenomenon dubbed quantum friction. A work published in ‘Nature Nanotechnology’ experimentally demonstrates this phenomenon – which was predicted in a previous theoretical study— at the interface between liquid water and graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms. Advanced ultrafast techniques were used to perform this study. These results could lead to applications in water purification and desalination processes and maybe even to liquid-based computers.

…

A liquid, such as water, is made up of small molecules that randomly move and constantly collide with each other. A solid, in contrast, is made of neatly arranged atoms that bathe in a cloud of electrons. The solid and the liquid worlds are assumed to interact only through collisions of the liquid molecules with the solid’s atoms: the liquid molecules do not “see” the solid’s electrons. Nevertheless, just over a year ago, a paradigm-shifting theoretical study proposed that at the water-carbon interface, the liquid’s molecules and the solid’s electrons push and pull on each other, slowing down the liquid flow: this new effect was called quantum friction. However, the theoretical proposal lacked experimental verification.

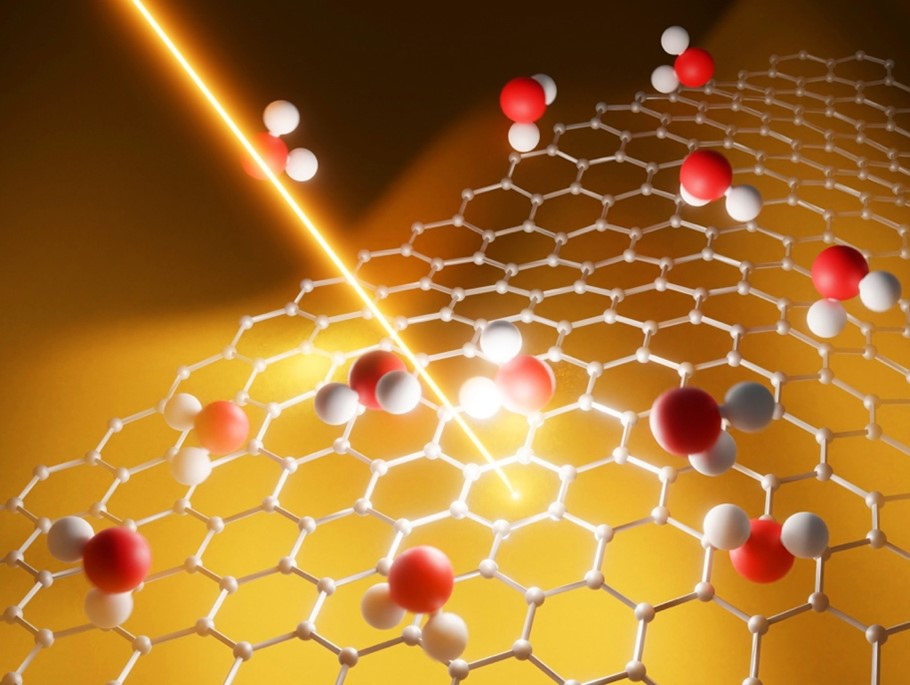

“We have now used lasers to see quantum friction at work,” explains study lead author Dr Nikita Kavokine, a researcher at the Max Planck Institute in Mainz and the Flatiron Institute in New York. The team studied a sample of graphene – a single monolayer of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb pattern. They used ultrashort red laser pulses (with a duration of only a millionth of a billionth of a second) to instantaneously heat up the graphene’s electron cloud. They then monitored its cooling with terahertz laser pulses, which are sensitive to the temperature of the graphene electrons. This technique is called optical pump – terahertz probe (OPTP) spectroscopy.

To their surprise, the electron cloud cooled faster when the graphene was immersed in water, while immersing the graphene in ethanol made no difference to the cooling rate. “This was yet another indication that the water-carbon couple is somehow special, but we still had to understand what exactly was going on,” Kavokine says. A possible explanation was that the hot electrons push and pull on the water molecules to release some of their heat: in other words, they cool through quantum friction. The researchers delved into the theory, and indeed: water-graphene quantum friction could explain the experimental data.

“It’s fascinating to see that the carrier dynamics of graphene keep surprising us with unexpected mechanisms, this time involving solid-liquid interactions with molecules none other than the omnipresent water,” comments Prof Klaas-Jan Tielrooij from ICN2 (Spain) and TU Eindhoven (The Netherlands). What makes water special here is that its vibrations, called hydrons, are in sync with the vibrations of the graphene electrons, called plasmons, so that the graphene-water heat transfer is enhanced through an effect known as resonance.

The experiments thus confirm the basic mechanism of solid-liquid quantum friction. This will have implications for filtration and desalination processes, in which quantum friction could be used to tune the permeation properties of the nanoporous membranes. “Our findings are not only interesting for physicists, but they also hold potential implications for electrocatalysis and photocatalysis at the solid-liquid interface,” says Xiaoqing Yu, PhD student at the Max Planck Institute in Mainz and first author of the work.

The discovery was down to bringing together an experimental system, a measurement tool and a theoretical framework that seldom go hand in hand. The key challenge is now to gain control over the water-electron interaction. “Our dream is to switch quantum friction on and off on demand,” Kavokine says. “This way, we could design smarter water filtration processes, or perhaps even fluid-based computers.”

The almost identical June 26, 2023 University of Manchester press release is here.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Electron cooling in graphene enhanced by plasmon–hydron resonance by Xiaoqing Yu, Alessandro Principi, Klaas-Jan Tielrooij, Mischa Bonn & Nikita Kavokine. Nature Nanotechnology (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41565-023-01421-3 Published: 22 June 2023

This paper is open access.