I have two news bits both of them concerned with magnets.

Patent for magnets that can be made without rare earths

I’m starting with the patent news first since this is (as the company notes in its news release) a “Landmark Patent Issued for Technology Critically Needed to Combat Chinese Monopoly.”

For those who don’t know, China supplies most of the rare earths used in computers, smart phones, and other devices. On general principles, having a single supplier dominate production of and access to a necessary material for devices that most of us rely on can raise tensions. Plus, you can’t mine for resources forever.

This December 19, 2023 Nanocrystal Technology LP news release heralds an exciting development (for the impatient, further down the page I have highlighted the salient sections),

Nanotechnology Discovery by 2023 Nobel Prize Winner Became Launch Pad to Create Permanent Magnets without Rare Earths from China

NEW YORK, NY, UNITED STATES, December 19, 2023 /EINPresswire.com/ — Integrated Nano-Magnetics Corp, a wholly owned subsidiary of Nanocrystal Technology LP, was awarded a patent for technology built upon a fundamental nanoscience discovery made by Aleksey Yekimov, its former Chief Scientific Officer.

This patent will enable the creation of strong permanent magnets which are critically needed for both industrial and military applications but cannot be manufactured without certain “rare earth” elements available mostly from China.

At a glittering awards ceremony held in Stockholm on December10, 2023, three scientists, Aleksey Yekimov, Louis Brus (Professor at Columbia University) and Moungi Bawendi (Professor at MIT) were honored with the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their discovery of the “quantum dot” which is now fueling practical applications in tuning the colors of LEDs, increasing the resolution of TV screens, and improving MRI imaging.

As stated by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, “Quantum dots are … bringing the greatest benefits to humankind. Researchers believe that in the future they could contribute to flexible electronics, tiny sensors, thinner solar cells, and encrypted quantum communications – so we have just started exploring the potential of these tiny particles.”

Aleksey Yekimov worked for over 19 years until his retirement as Chief Scientific Officer of Nanocrystals Technology LP, an R & D company in New York founded by two Indian-American entrepreneurs, Rameshwar Bhargava and Rajan Pillai.

Yekimov, who was born in Russia, had already received the highest scientific honors for his work before he immigrated to USA in 1999. Yekimov was greatly intrigued by Nanocrystal Technology’s research project and chose to join the company as its Chief Scientific Officer.

During its early years, the company worked on efficient light generation by doping host nanoparticles about the same size as a quantum dot with an additional impurity atom. Bhargava came up with the novel idea of incorporating a single impurity atom, a dopant, into a quantum dot sized host, and thus achieve an extraordinary change in the host material’s properties such as inducing strong permanent magnetism in weak, readily available paramagnetic materials. To get a sense of the scale at which nanotechnology works, and as vividly illustrated by the Nobel Foundation, the difference in size between a quantum dot and a soccer ball is about the same as the difference between a soccer ball and planet Earth.

Currently, strong permanent magnets are manufactured from “rare earths” available mostly in China which has established a near monopoly on the supply of rare-earth based strong permanent magnets. Permanent magnets are a fundamental building block for electro-mechanical devices such as motors found in all automobiles including electric vehicles, trucks and tractors, military tanks, wind turbines, aircraft engines, missiles, etc. They are also required for the efficient functioning of audio equipment such as speakers and cell phones as well as certain magnetic storage media.

The existing market for permanent magnets is $28 billion and is projected to reach $50 billion by 2030 in view of the huge increase in usage of electric vehicles. China’s overwhelming dominance in this field has become a matter of great concern to governments of all Western and other industrialized nations. As the Wall St. Journal put it, China’s now has a “stranglehold” on the economies and security of other countries.

The possibility of making permanent magnets without the use of any rare earths mined in China has intrigued leading physicists and chemists for nearly 30 years. On December 19, 2023, a U.S. patent with the title ‘’Strong Non Rare Earth Permanent Magnets from Double Doped Magnetic Nanoparticles” was granted to Integrated Nano-Magnetics Corp. [emphasis mine] Referring to this major accomplishment Bhargava said, “The pioneering work done by Yekimov, Brus and Bawendi has provided the foundation for us to make other discoveries in nanotechnology which will be of great benefit to the world.”

I was not able to find any company websites. The best I could find is a Nanocrystals Technology LinkedIn webpage and some limited corporate data for Integrated Nano-Magnetics on opencorporates.com.

Twisted magnets and brain-inspired computing

This research offers a pathway to neuromorphic (brainlike) computing with chiral (or twisted) magnets, which, as best as I understand it, do not require rare earths. From a November13, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily,

A form of brain-inspired computing that exploits the intrinsic physical properties of a material to dramatically reduce energy use is now a step closer to reality, thanks to a new study led by UCL [University College London] and Imperial College London [ICL] researchers.

In the new study, published in the journal Nature Materials, an international team of researchers used chiral (twisted) magnets as their computational medium and found that, by applying an external magnetic field and changing temperature, the physical properties of these materials could be adapted to suit different machine-learning tasks.

…

A November 9, 2023 UCL press release (also on EurekAlert but published November 13, 2023), which originated the news item, fill s in a few more details about the research,

Dr Oscar Lee (London Centre for Nanotechnology at UCL and UCL Department of Electronic & Electrical Engineering), the lead author of the paper, said: “This work brings us a step closer to realising the full potential of physical reservoirs to create computers that not only require significantly less energy, but also adapt their computational properties to perform optimally across various tasks, just like our brains.

“The next step is to identify materials and device architectures that are commercially viable and scalable.”

Traditional computing consumes large amounts of electricity. This is partly because it has separate units for data storage and processing, meaning information has to be shuffled constantly between the two, wasting energy and producing heat. This is particularly a problem for machine learning, which requires vast datasets for processing. Training one large AI model can generate hundreds of tonnes of carbon dioxide.

Physical reservoir computing is one of several neuromorphic (or brain inspired) approaches that aims to remove the need for distinct memory and processing units, facilitating more efficient ways to process data. In addition to being a more sustainable alternative to conventional computing, physical reservoir computing could be integrated into existing circuitry to provide additional capabilities that are also energy efficient.

In the study, involving researchers in Japan and Germany, the team used a vector network analyser to determine the energy absorption of chiral magnets at different magnetic field strengths and temperatures ranging from -269 °C to room temperature.

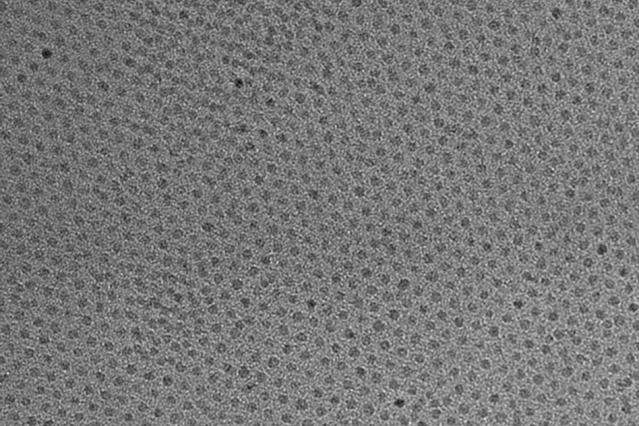

They found that different magnetic phases of chiral magnets excelled at different types of computing task. The skyrmion phase, where magnetised particles are swirling in a vortex-like pattern, had a potent memory capacity apt for forecasting tasks. The conical phase, meanwhile, had little memory, but its non-linearity was ideal for transformation tasks and classification – for instance, identifying if an animal is a cat or dog.

Co-author Dr Jack Gartside, of Imperial College London, said: “Our collaborators at UCL in the group of Professor Hidekazu Kurebayashi recently identified a promising set of materials for powering unconventional computing. These materials are special as they can support an especially rich and varied range of magnetic textures. Working with the lead author Dr Oscar Lee, the Imperial College London group [led by Dr Gartside, Kilian Stenning and Professor Will Branford] designed a neuromorphic computing architecture to leverage the complex material properties to match the demands of a diverse set of challenging tasks. This gave great results, and showed how reconfiguring physical phases can directly tailor neuromorphic computing performance.”

The work also involved researchers at the University of Tokyo and Technische Universität München and was supported by the Leverhulme Trust, Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC), Imperial College London President’s Excellence Fund for Frontier Research, Royal Academy of Engineering, the Japan Science and Technology Agency, Katsu Research Encouragement Award, Asahi Glass Foundation, and the DFG (German Research Foundation).

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Task-adaptive physical reservoir computing by Oscar Lee, Tianyi Wei, Kilian D. Stenning, Jack C. Gartside, Dan Prestwood, Shinichiro Seki, Aisha Aqeel, Kosuke Karube, Naoya Kanazawa, Yasujiro Taguchi, Christian Back, Yoshinori Tokura, Will R. Branford & Hidekazu Kurebayashi. Nature Materials volume 23, pages 79–87 (2024) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-023-01698-8 Published online: 13 November 2023 Issue Date: January 2024

This paper is open access.