Thank you to Nagoya University (Japan) for making this image available.

From a June 28, 2021 Nagoya University press release (also on EurekAlert),

A group of researchers at Nagoya University, Japan, have developed a new method for quickly and efficiently synthesizing nanographenes, a type of nanocarbon with great potential as a next generation material.

Nanographenes are the part structures of graphene, which is a sheet of carbon atoms around 3 nanometers thick with particular potential for use in semiconductor development, having electron mobility several hundred times better than current generation materials. Graphene was first isolated in 2004, a discovery which received the 2010 Nobel Prize in physics, making it a very new material which is currently the subject of a great deal of research.

With magnetic and electric characteristics beyond those of graphene, nanographenes are equally of interest to scientists in the nanocarbon research field. The biggest obstacle, albeit an exciting one, faced by researchers is the sheer number of potential nanographenes. The number of potentially possible nanographene structures increases with the number of benzene rings (6 atoms of carbon in a hexagonal formation) to make them. For example, even a relatively small 10 benzene ring nanographene may have up to 16,000 variants. As each nanographene has different physical characteristics, the key to applied nanographene research is to identify the relationship between the structure and characteristics of as many nanographenes as possible.

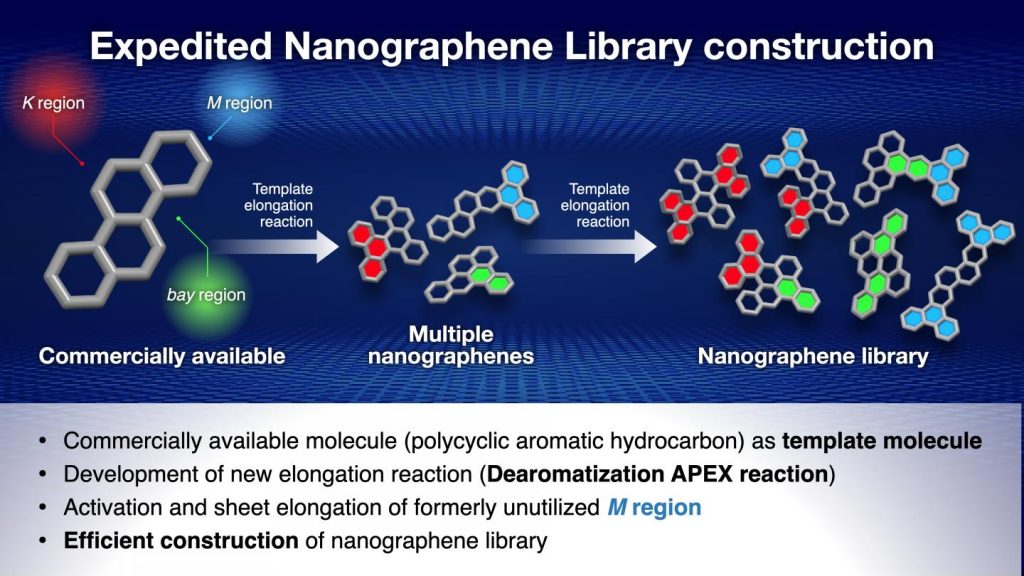

Thus, scientists’ task is to create a nanographene library, containing data on the properties of as many nanographenes as possible. However, the current method of nanographene synthesis, known as a coupling reaction, is a multi-step process which produces one single nanographene. Thus, to create a 100-nanographene library, 100 separate coupling reactions would have to be carried out. Even this would be a significant undertaking, rendering the construction of a truly comprehensive nanographene library practically impossible.

To solve this problem, the Nagoya University research group, led by Professor Kenichiro Itami, have been working on the APEX reaction, a reaction which uses polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons as templates to synthesize nanographenes. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons have three areas of their structure – known as the K region, M region and bay region – which can be elongated in an APEX reaction, producing three nanographenes. These nanographenes can then be further elongated in a second reaction, meaning that a large number of nanographenes can be synthesized from a single polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon template molecule.

With Professor Itami’s group having already developed the K region APEX reaction, and another group of scientists having done so for the bay region, they turned their attention to the M region. They activated the M region using the 1950 Nobel Prize winning Diels-Alder reaction, and succeeded in carrying out an elongation reaction on the activated M region, thus rendering all three possible sites on the polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons capable of synthesizing nanographenes.

The researchers were able to produce 13 nanographenes with three APEX reactions, with most of these being previously unseen structures, thus proving both the efficiency and usefulness of this new method.

This exciting new piece of research and its potential to accelerate the creation of nanographene libraries is a step towards the development of the next generation of materials, which have the potential to revolutionize semiconductors and solar energy and improve lives all around the world.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Diversity-oriented synthesis of nanographenes enabled by dearomative annulative π-extension by Wataru Matsuoka, Hideto Ito, David Sarlah & Kenichiro Itami. Nature Communications volume 12, Article number: 3940 (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-24261-y Published 24 June 2021

This paper is open access.