German scientists have observed a phenomenon (light-matter interaction) that exists for attoseconds. (For anyone unfamiliar with that scale, micro = a millionth, nano = a billionth, pico = a trillionth, femto = a quadrillionth, and atto = a quintillionth.) A May 31, 2016 news item on Nanowerk announces the work (Note: A link has been removed),

Physicists of the Laboratory for Attosecond Physics at the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics and the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität Munich in collaboration with scientists from the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg have observed a light-matter phenomenon in nano-optics, which lasts only attoseconds (“Attosecond nanoscale near-field sampling”).

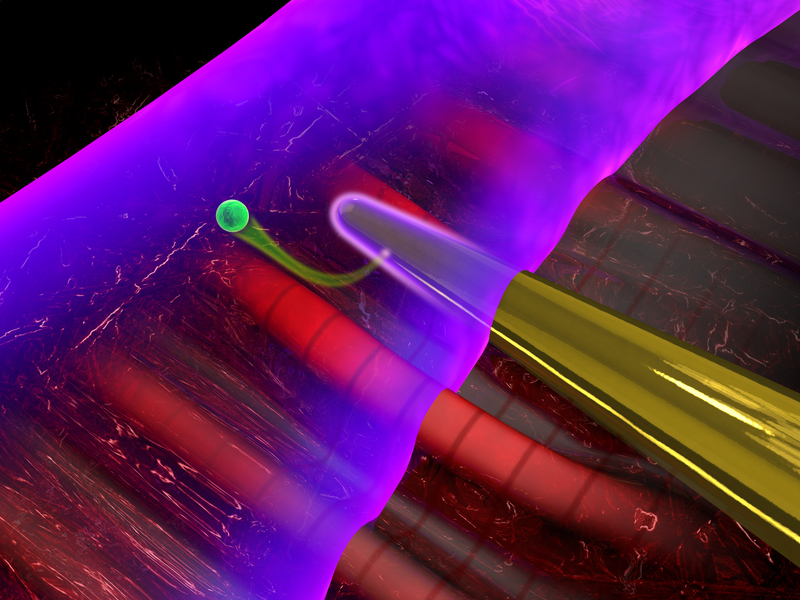

Here’s an illustration of the work,

When laser light interacts with a nanoneedle (yellow), electromagnetic near-fields are formed at its surface. A second laser pulse (purple) emits an electron (green) from the needle, permitting to characterize the near-fields.

Image: Christian Hackenberger

A May 31, 2016 Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics press release (also on EurekAlert) by Thorsten Naeser, which originated the news item, describes the phenomenon and the work in more detail,

The interaction between light and matter is of key importance in nature, the most prominent example being photosynthesis. Light-matter interactions have also been used extensively in technology, and will continue to be important in electronics of the future. A technology that could transfer and save data encoded on light waves would be 100.000-times faster than current systems. A light-matter interaction which could pave the way to such light-driven electronics has been investigated by scientists from the Laboratory for Attosecond Physics (LAP) at the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität (LMU) and the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics (MPQ), in collaboration with colleagues from the Chair for Laser Physics at the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg. The researchers sent intense laser pulses onto a tiny nanowire made of gold. The ultrashort laser pulses excited vibrations of the freely moving electrons in the metal. This resulted in electromagnetic ‘near-fields’ at the surface of the wire. The near-fields oscillated with a shift of a few hundred attoseconds with respect to the exciting laser field (one attosecond is a billionth of a billionth of a second). This shift was measured using attosecond light pulses which the scientists subsequently sent onto the nanowire.

When light illuminates metals, it can result in curious things in the microcosm at the surface. The electromagnetic field of the light excites vibrations of the electrons in the metal. This interaction causes the formation of ‘near-fields’ – electromagnetic fields localized close to the surface of the metal.

How near-fields behave under the influence of light has now been investigated by an international team of physicists at the Laboratory for Attosecond Physics of the Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität and the Max Planck Institute of Quantum Optics in close collaboration with scientists of the Chair for Laser Physics at the Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg.

The researchers sent strong infrared laser pulses onto a gold nanowire. These laser pulses are so short that they are composed of only a few oscillations of the light field. When the light illuminated the nanowire it excited collective vibrations of the conducting electrons surrounding the gold atoms. Through these electron motions, near-fields were created at the surface of the wire.

The physicists wanted to study the timing of the near-fields with respect to the light fields. To do this they sent a second light pulse with an extremely short duration of just a couple of hundred attoseconds onto the nanostructure shortly after the first light pulse. The second flash released individual electrons from the nanowire. When these electrons reached the surface, they were accelerated by the near-fields and detected. Analysis of the electrons showed that the near-fields were oscillating with a time shift of about 250 attoseconds with respect to the incident light, and that they were leading in their vibrations. In other words: the near-field vibrations reached their maximum amplitude 250 attoseconds earlier than the vibrations of the light field.

“Fields and surface waves at nanostructures are of central importance for the development of lightwave-electronics. With the demonstrated technique they can now be sharply resolved.”, explained Prof. Matthias Kling, the leader of the team carrying out the experiments in Munich.

The experiments pave the way towards more complex studies of light-matter interaction in metals that are of interest in nano-optics and the light-driven electronics of the future. Such electronics would work at the frequencies of light. Light oscillates a million billion times per second, i.e. with petahertz frequencies – about 100.000 times faster than electronics available at the moment. The ultimate limit of data processing could be reached.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Attosecond nanoscale near-field sampling by B. Förg, J. Schötz, F. Süßmann, M. Förster, M. Krüger, B. Ahn, W. A. Okell, K. Wintersperger, S. Zherebtsov, A. Guggenmos, V. Pervak, A. Kessel, S. A. Trushin, A. M. Azzeer, M. I. Stockman, D. Kim, F. Krausz, P. Hommelhoff, & M. F. Kling. Nature Communications 7, Article number: 11717 doi:10.1038/ncomms11717 Published 31 May 2016

This paper is open access.