A Feb. 8, 2014 news item on Nanowerk features a US Government Accountability Office (GAO) publication announcement (Note: A link has been removed),

In a new report on nanotechnology manufacturing (or nanomanufacturing) released yesterday (“Nanomanufacturing: Emergence and Implications for U.S. Competitiveness, the Environment, and Human Health”; pdf), the U.S. Government Accountability Office finds flaws in America’s approach to many things nano.

At a July 2013 forum, participants from industry, government, and academia discussed the future of nanomanufacturing; investments in nanotechnology R&D and challenges to U.S. competitiveness; ways to enhance U.S. competitiveness; and EHS concerns.

A summary and a PDF version of the report, published Jan. 31, 2014, can be found here on the GAO’s GAO-14-181SP (report’s document number) webpage. From the summary,

The forum’s participants described nanomanufacturing as a future megatrend that will potentially match or surpass the digital revolution’s effect on society and the economy. They anticipated further scientific breakthroughs that will fuel new engineering developments; continued movement into the manufacturing sector; and more intense international competition.

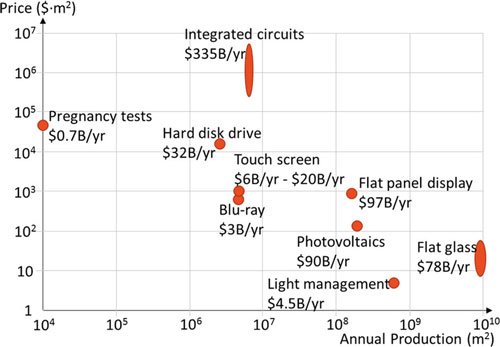

Although limited data on international investments made comparisons difficult, participants viewed the U.S. as likely leading in nanotechnology research and development (R&D) today. At the same time, they identified several challenges to U.S. competitiveness in nanomanufacturing, such as inadequate U.S. participation and leadership in international standard setting; the lack of a national vision for a U.S. nanomanufacturing capability; some competitor nations’ aggressive actions and potential investments; and funding or investment gaps in the United States (illustrated in the figure, below), which may hamper U.S. innovators’ attempts to transition nanotechnology from R&D to full-scale manufacturing.

![[downloaded from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-181SP]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/US_GAO_nanomanufacturing-300x120.png)

[downloaded from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-181SP]

I read through (skimmed) this 125pp (PDF version; 119 pp. print version) report and allthough it’s not obvious in the portion I’ve excerpted from the summary or in the following sections, the participants did seem to feel that the US national nanotechnology effort was in relatively good shape overall but with some shortcomings that may become significant in the near future.

First, government investment illustrates the importance the US has placed on its nanotechnology efforts (excerpted from p. 11 PDF; p. 5 print),

Focusing on U.S. public investment since 2001, the overall growth in the funding of nanotechnology has been substantial, as indicated by the funding of the federal interagency National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI), with a cumulative investment of about $18 billion for fiscal years 2001 through 20133. Adding the request for fiscal year 2014 brings the total to almost $20 billion. However, the amounts budgeted in recent years have not shown an increasing trend.

Next, the participants in the July 2013 forum focused on four innovations in four different industry sectors as a means of describing the overall situation (excerpted from p. 16 PDF; p. 10 print):

Semiconductors (Electronics and semiconductors)

Battery-powered vehicles (Energy and power)

Nano-based concrete (Materials and chemical industries)

Nanotherapeutics (Pharmaceuticals, biomedical, and biotechnology)

There was some talk about nanotechnology as a potentially disruptive technology,

Nanomanufacturing could eventually bring disruptive innovation and the creation of new jobs—at least for the nations that are able to compete globally. According to the model suggested by Christensen (2012a; 2012b), which was cited by a forum participant, the widespread disruption of existing industries (and their supply chains) can occur together with the generation of broader markets, which can lead to net job creation, primarily for nations that bring the disruptive technology to market. The Ford automobile plant (with its dramatic changes in the efficient assembly of vehicles) again provides an historical example: mass – produced automobiles made cheaply enough—through economies of scale—were sold to vast numbers of consumers, replacing horse and buggy transportation and creating jobs to (1) manufacture large numbers of cars and develop the supply chain; (2) retail new cars; and (3) service them. The introduction of minicomputers and then personal computers in the 1980s and 1990s provides another historical example; the smaller computers disrupted the dominant mainframe computing industry (Christensen et al. 2000). Personal computers were provided to millions of homes, and an analyst in the Bureau of Labor Statistics (Freeman 1996) documented the creation of jobs in related areas such as selling home computers and software. According to Christensen (2012b), “[A]lmost all net growth in jobs in America has been created by companies that were empowering—companies that made complicated things affordable and accessible so that more people could own them and use them.”14 As a counterpoint, a recent report analyzing manufacturing today (Manyika et al. 2012, 4) claims that manufacturing “cannot be expected to create mass employment in advanced economies on the scale that it did decades ago.”

Interestingly, there is no mention in any part of the report of the darker sides of a disruptive technology. After all, there were people who were very, very upset over the advent of computers. For example, a student (I was teaching a course on marketing communication) once informed me that she and her colleagues used to regularly clear bullets from the computerized equipment they were sending up to the camps (memory fails as to whether these were mining or logging camps) in northern British Columbia in the early days of the industry’s computerization.

Getting back to the report, I wasn’t expecting to see that one of the perceived problems is the US failure to participate in setting standards (excerpted from p. 23 PDF; p. 17 print),

Lack of sufficient U.S. participation in setting standards for nanotechnology or nanomanufacturing. Some participants discussed a possible need for a stronger role for the United States in setting commercial standards for nanomanufactured goods (including defining basic terminology in order to sell products in global markets).17

The participants discussed the ‘Valley of Death’ and the ‘Missing Middle’ (excerpted from pp. 31-2 PDF; pp. 25-6 print)

Forum participants said that middle-stage funding, investment, and support gaps occur for not only technology innovation but also manufacturing innovation. They described the Valley of Death (that is, the potential lack of funding or investment that may characterize the middle stages in the development of a technology or new product) and the Missing Middle (that is, a similar lack of adequate support for the middle stages of developing a manufacturing process or approach), as explained below.

The Valley of Death refers to a gap in funding or investment that can occur after research on a new technology and its initial development—for example, when the technology moves beyond tests in a controlled laboratory setting.22 In the medical area, participants said the problem of inadequate funding /investment may be exacerbated by requirements for clinical trials. To illustrate, one participant said that $10 million to $20 million is needed to bring a new medical treatment into clinical trials, but “support from [a major pharmaceutical company] typically is not forthcoming until Phase II clinical trials,” resulting in a Valley of Death for some U.S. medical innovations. Another participant mentioned an instance where a costly trial was required for an apparently low risk medical device—and this participant tied high costs of this type to potential difficulties that medical innovators might have obtaining venture capital. A funding /investment gap at this stage can prevent further development of a technology.

The term Missing Middle has been used to refer to the lack of funding/investment that can occur with respect to manufacturing innovation—that is, maturing manufacturing capabilities and processes to produce technologies at scale, as illustrated in figure 8.23 Here, another important lack of support may be the absence of what one participant called an “industrial commons” to sustain innovation within a manufacturing sector.24 Logically, successful transitioning across the middle stages of manufacturing development is a prerequisite to achieving successful new approaches to manufacturing at scale.

There was discussion of the international scene with regard to the ‘Valley of Death’ and the ‘Missing Middle’ (excerpted from pp. 41-2 PDF; pp. 35-6 print)

Participants said that the Valley of Death and Missing Middle funding and investment gaps, which are of concern in the United States, do not apply to the same extent in some other countries—for example, China and Russia—or are being addressed. One participant said that other countries in which these gaps have occurred “have zeroed in [on them] with a laser beam.” Another participant summed up his view of the situation with the statement: “Government investments in establishing technology platforms, technology transfer, and commercialization are higher in other countries than in the United States.” He further stated that those making higher investments include China, Russia, and the European Union.

Multiple participants referred to the European Commission’s upcoming Horizon 2020 program, which will have major funding extending over 7 years. In addition to providing major funding for fundamental research, the Horizon 2020 website states that the program will help to:

“…bridge the gap between research and the market by, for example, helping innovative enterprises to develop their technological breakthroughs into viable products with real commercial potential. This market-driven approach will include creating partnerships with the private sector and Member States to bring together the resources needed.”

A key program within Horizon 2020 consists of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT), which as illustrated in the “Knowledge Triangle” shown figure 11, below, emphasizes the nexus of business, research, and higher education. The 2014-2020 budget for this portion of Horizon 2020 is 2.7 billion euros (or close to $3.7 billion in U.S. dollars as of January 2014).

As is often the case with technology and science, participants mentioned intellectual property (IP) (excerpted from pp. 43-44 PDF; pp. 37-8 print),

Several participants discussed threats to IP associated with global competition.43 One participant described persistent attempts by other countries (or by certain elements in other countries) to breach information systems at his nanomanufacturing company. Another described an IP challenge pertaining to research at U.S. universities, as follows:

•due to a culture of openness, especially among students, ideas and research are “leaking out” of universities prior to the initial researchers having patented or fully pursued them;

•there are many foreign students at U.S. universities; and

•there is a current lack of awareness about “leakage” and of university policies or training to counter it.

Additionally, one of our earlier interviewees said that one country targeted. Specific research projects at U.S. universities—and then required its own citizen-students to apply for admission to each targeted U.S. university and seek work on the targeted project.

Taken together with other factors, this situation can result in an overall failure to protect IP and undermine U.S. research competitiveness. (Although a culture of openness and the presence of foreign students are generally considered strengths of the U.S. system, in this context such factors could represent a challenge to capturing the full value of U.S. investments.)

I would have liked to have seen a more critical response to the discussion about IP issues given the well-documented concerns regarding IP and its depressing affect on competitiveness as per my June 28, 2012 posting titled: Billions lost to patent trolls; US White House asks for comments on intellectual property (IP) enforcement; and more on IP, my Oct. 10, 2012 posting titled: UN’s International Telecommunications Union holds patent summit in Geneva on Oct. 10, 2012, and my Oct. 31, 2011 posting titled: Patents as weapons and obstacles, amongst many, many others here.

This is a very readable report and it answered a few questions for me about the state of nanomanufacturing.

ETA Feb. 10, 2014 at 2:45 pm PDT, The Economist magazine has a Feb. 7, 2014 online article about this new report from the US.

ETA April 2, 2014: There’s an April 1, 2014 posting about this report on the Foresight Institute blog titled, US government report highlights flaws in US nanotechnology effort.

![[downloaded from http://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-14-181SP]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/US_GAO_nanomanufacturing-300x120.png)