If you’re hoping for a Rumpelstiltskin reference (there is more about the fairy tale at the end of this posting) and despite the press release’s headline, you won’t find it in this August 10, 2020 news item on Nanowerk,

When nanocellulose is combined with various types of metal nanoparticles, materials are formed with many new and exciting properties. They may be antibacterial, change colour under pressure, or convert light to heat.

“To put it simply, we make gold from nanocellulose”, says Daniel Aili, associate professor in the Division of Biophysics and Bioengineering at the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Biology at Linköping University.

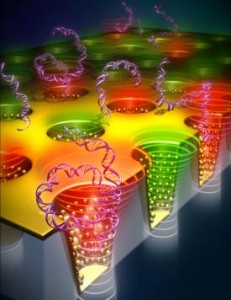

The research group, led by Daniel Aili, has used a biosynthetic nanocellulose produced by bacteria and originally developed for wound care. The scientists have subsequently decorated the cellulose with metal nanoparticles, principally silver and gold. The particles, no larger than a few billionths of a metre, are first tailored to give them the properties desired, and then combined with the nanocellulose.

An August 10, 2020 Linköping University press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item,expands on a few details about the work (sob … without mentioning Rumpelstiltskin),

“Nanocellulose consists of thin threads of cellulose, with a diameter approximately one thousandth of the diameter of a human hair. The threads act as a three-dimensional scaffold for the metal particles. When the particles attach themselves to the cellulose, a material that consists of a network of particles and cellulose forms”, Daniel Aili explains.

The researchers can determine with high precision how many particles will attach, and their identities. They can also mix particles of different metals and with different shapes – spherical, elliptical and triangular.

In the first part of a scientific article published in Advanced Functional Materials, the group describes the process and explains why it works as it does. The second part focusses on several areas of application.

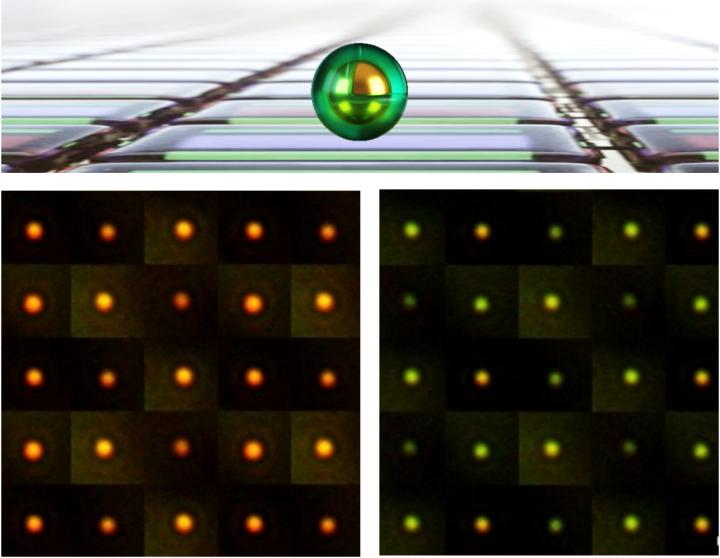

One exciting phenomenon is the way in which the properties of the material change when pressure is applied. Optical phenomena arise when the particles approach each other and interact, and the material changes colour. As the pressure increases, the material eventually appears to be gold.

“We saw that the material changed colour when we picked it up in tweezers, and at first we couldn’t understand why”, says Daniel Aili.

The scientists have named the phenomenon “the mechanoplasmonic effect”, and it has turned out to be very useful. A closely related application is in sensors, since it is possible to read the sensor with the naked eye. An example: If a protein sticks to the material, it no longer changes colour when placed under pressure. If the protein is a marker for a particular disease, the failure to change colour can be used in diagnosis. If the material changes colour, the marker protein is not present.

Another interesting phenomenon is displayed by a variant of the material that absorbs light from a much broader spectrum visible light and generates heat. This property can be used for both energy-based applications and in medicine.

“Our method makes it possible to manufacture composites of nanocellulose and metal nanoparticles that are soft and biocompatible materials for optical, catalytic, electrical and biomedical applications. Since the material is self-assembling, we can produce complex materials with completely new well-defined properties,” Daniel Aili concludes.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Self‐Assembly of Mechanoplasmonic Bacterial Cellulose–Metal Nanoparticle Composites by Olof Eskilson, Stefan B. Lindström, Borja Sepulveda, Mohammad M. Shahjamali, Pau Güell‐Grau, Petter Sivlér, Mårten Skog, Christopher Aronsson, Emma M. Björk, Niklas Nyberg, Hazem Khalaf, Torbjörn Bengtsson, Jeemol James, Marica B. Ericson, Erik Martinsson, Robert Selegård, Daniel Aili. Advanced Functional Materials DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adfm.202004766 First published: 09 August 2020

This paper is open access.

As for Rumpelstiltskin, there’s this abut the story’s origins and its cross-cultural occurrence, from its Wikipedia entry,

“Rumpelstiltskin” (/ˌrʌmpəlˈstɪltskɪn/ RUMP-əl-STILT-skin[1]) is a fairy tale popularly associated with Germany (where it is known as Rumpelstilzchen). The tale was one collected by the Brothers Grimm in the 1812 edition of Children’s and Household Tales. According to researchers at Durham University and the NOVA University Lisbon, the story originated around 4,000 years ago.[2][3] However, many biases led some to take the results of this study with caution.[4]

…

The same story pattern appears in numerous other cultures: Tom Tit Tot in England (from English Fairy Tales, 1890, by Joseph Jacobs); The Lazy Beauty and her Aunts in Ireland (from The Fireside Stories of Ireland, 1870 by Patrick Kennedy); Whuppity Stoorie in Scotland (from Robert Chambers’s Popular Rhymes of Scotland, 1826); Gilitrutt in Iceland; جعيدان (Joaidane “He who talks too much”) in Arabic; Хламушка (Khlamushka “Junker”) in Russia; Rumplcimprcampr, Rampelník or Martin Zvonek in the Czech Republic; Martinko Klingáč in Slovakia; “Cvilidreta” in Croatia; Ruidoquedito (“Little noise”) in South America; Pancimanci in Hungary (from A Csodafurulya, 1955, by Emil Kolozsvári Grandpierre, based on the 19th century folktale collection by László Arany); Daiku to Oniroku (大工と鬼六 “A carpenter and the ogre”) in Japan and Myrmidon in France.

An earlier literary variant in French was penned by Mme. L’Héritier, titled Ricdin-Ricdon.[5] A version of it exists in the compilation Le Cabinet des Fées, Vol. XII. pp. 125-131.

The Cornish tale of Duffy and the Devil plays out an essentially similar plot featuring a “devil” named Terry-top.

All these tales are Aarne–Thompson type 500, “The Name of the Helper”.[6]

…

Should you be curious about the story as told by the Brothers Grimm, here’s the beginning to get you started (from the grimmstories.com Rumpelstiltskin webpage),

There was once a miller who was poor, but he had one beautiful daughter. It happened one day that he came to speak with the king, and, to give himself consequence, he told him that he had a daughter who could spin gold out of straw. The king said to the miller: “That is an art that pleases me well; if thy daughter is as clever as you say, bring her to my castle to-morrow, that I may put her to the proof.”

When the girl was brought to him, he led her into a room that was quite full of straw, and gave her a wheel and spindle, and said: “Now set to work, and if by the early morning thou hast not spun this straw to gold thou shalt die.” And he shut the door himself, and left her there alone. And so the poor miller’s daughter was left there sitting, and could not think what to do for her life: she had no notion how to set to work to spin gold from straw, and her distress grew so great that she began to weep. Then all at once the door opened, and in came a little man, who said: “Good evening, miller’s daughter; why are you crying?”

…

Enjoy! BTW, should you care to, you can find three other postings here tagged with ‘Rumpelstiltskin’. I think turning dross into gold is a popular theme in applied science.

![[downloaded from http://www.netatmo.com/en-US/product/june]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/June_PhotovoltaicBraceletBrooch-300x109.jpg)