The research comes from Korea’s Institute of Basic Science and was announced in a March 22, 2016 news article by Lee Chi-dong for Yonhap News Agency,

A team of South Korean scientists announced Tuesday [March 22, 2016] that they have developed a wearable device, based on nanotechnology, for more convenient diabetes monitoring and therapy.

The graphene-using “smart patch” has improved the accuracy of blood sugar level measurements as it checks not only glucose in sweat but also temperature and acidity, according to the Institute for Basic Science (IBS) located in Daejeon, some 160 kilometers south of Seoul.

Existing smart patches gauge blood sugar merely in sweat.

Google is working on “smart contact lens” with an ultra-tiny super sensitive glucose sensor for tear fluid. Its accuracy remains a question amid concerns about adverse effects on eye health.

A March 21, 2016 IBS press release on EurekAlert provides more details about the work,

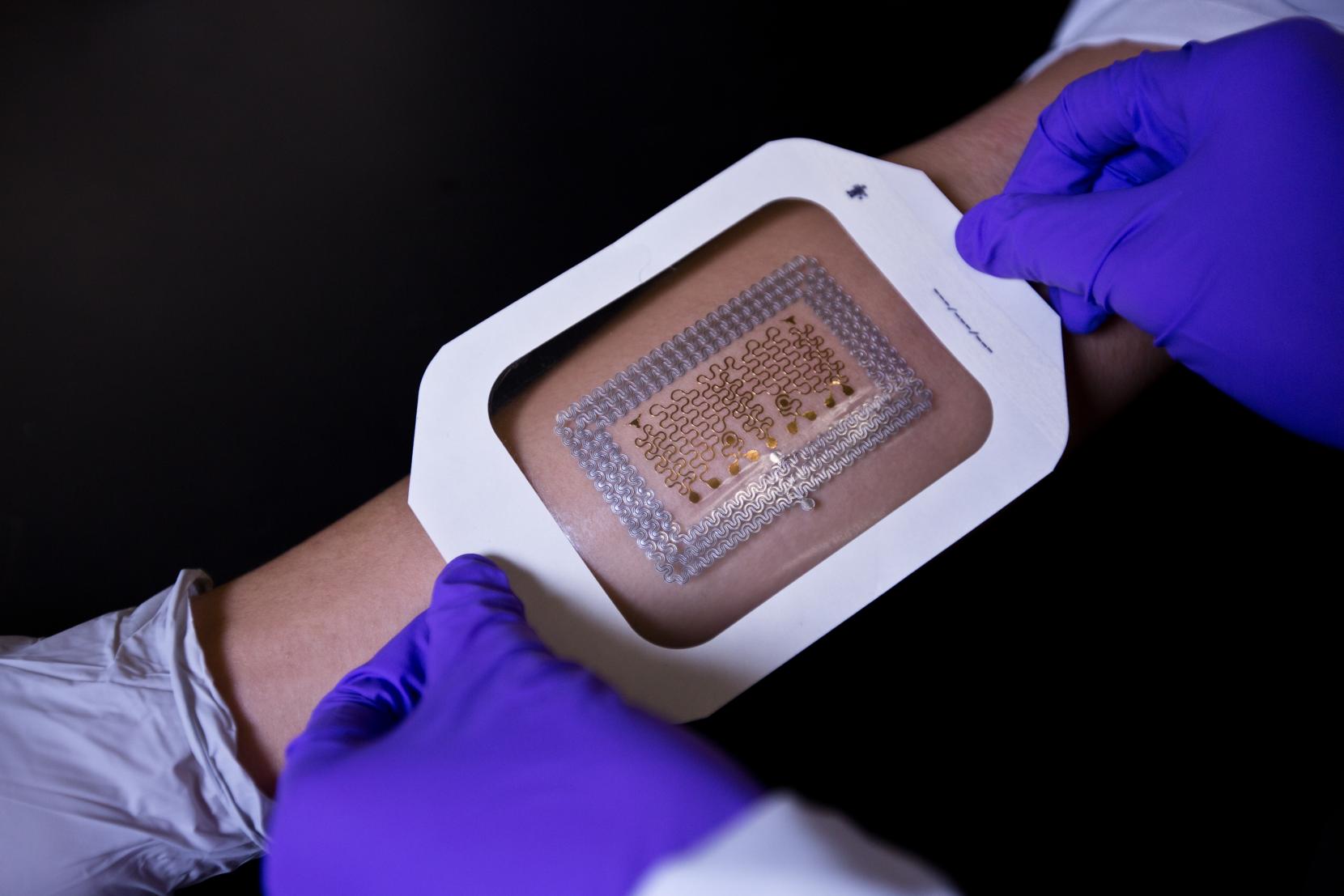

A scientific team from the Center for Nanoparticle Research at IBS has created a wearable GP [graphene]-based patch that allows accurate diabetes monitoring and feedback therapy by using human sweat. The researchers improved the device’s detecting capabilities by integrating electrochemically active and soft functional materials on the hybrid of gold-doped graphene and a serpentine-shape gold mesh. The device’s pH and temperature monitoring functions enable systematic corrections of sweat glucose measurements as the enzyme-based glucose sensor is affected by pH (blood acidity levels) and temperature.

Diabetes and regulating glucose levels

Insulin is produced in the pancreas and regulates the use of glucose, maintaining a balance in blood sugar levels. Diabetes causes an imbalance: insufficient amounts of insulin results in high blood glucose levels, known as hyperglycemia. Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes with no known cure. It affects some 3 million Koreans with the figure increasing due to dietary patterns and an aging society. The current treatments available to diabetics are painful, inconvenient and costly; regular visits to a doctor and home testing kits are needed to record glucose levels. Patients also have to inject uncomfortable insulin shots to regulate glucose levels. There is a significant need for non-invasive, painless, and stress-free monitoring of important markers of diabetes using multifunctional wearable devices. The IBS device facilitates this and thereby reduces the lengthy and expensive cycles of visiting doctors and pharmacies.

Components of the graphene-based wearable device

KIM Dae-Hyeong, a scientist from the Center for Nanoparticle Research, describes the vast array of components: “Our wearable GP-based device is capable of not only sweat-based glucose and pH monitoring but also controlled transcutaneous drug delivery through temperature-responsive microneedles. Precise measurement of sweat glucose concentrations are used to estimate the levels of glucose in the blood of a patient. The device retains its original sensitivity after multiple uses, thereby allowing for multiple treatments. The connection of the device to a portable/ wireless power supply and data transmission unit enables the point-of-care treatment of diabetes.” The professor went on to describe how the device works, “The patch is applied to the skin where sweat-based glucose monitoring begins on sweat generation. The humidity sensor monitors the increase in relative humidity (RH). It takes an average of 15 minutes for the sweat-uptake layer of the patch to collect sweat and reach a RH over 80% at which time glucose and pH measurements are initiated.”

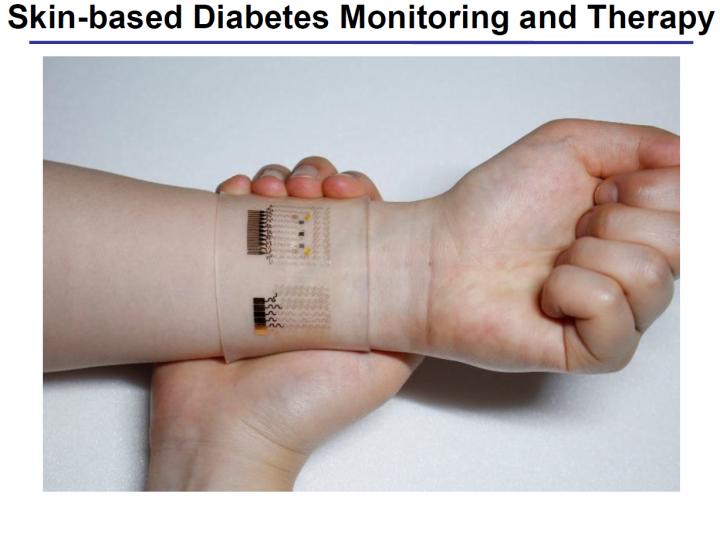

Merits of the device and drug administration

The device shows dramatic advances over current treatment methods by allowing non-invasive treatments. During the team’s research, two healthy males participated in tests to demonstrate the sweat-based glucose sensing of the device. Glucose and pH levels of both subjects were recorded; a statistical analysis confirmed the reliable correlation between sweat glucose data from the diabetes patch and those from commercial glucose tests. If abnormally high levels of glucose are detected, a drug is released into a patient’s bloodstream via drug loaded microneedles. The malleable, semi-transparent skin-like appearance of the GP device provides easy and comfortable contact with human skin, allowing the sensors to remain unaffected by any skin deformations. This enables stable sensing and efficient drug delivery.

The scientific team also demonstrated the therapeutic effects by experimenting on diabetic (db/db) mice. Treatment began by applying the device near the abdomen of the db mouse. Microneedles pierced the skin of the mouse and released Metformin, an insulin regulating drug, into the bloodstream. The group treated with microneedles showed a significant suppression of blood glucose concentrations with respect to control groups. “One can easily replace the used microneedles with new ones. Treatment with Metformin through the skin is more efficient than that through the digestive system because the drug is directly introduced into metabolic circulation through the skin,” commented KIM Dae-Hyeong. He went on: “These advances using nanomaterials and devices provide new opportunities for the treatment of chronic diseases like diabetes.”

The researchers have made an image illustrating their work available,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A graphene-based electrochemical device with thermoresponsive microneedles for diabetes monitoring and therapy by Hyunjae Lee, Tae Kyu Choi, Young Bum Lee, Hye Rim Cho, Roozbeh Ghaffari, Liu Wang, Hyung Jin Choi, Taek Dong Chung, Nanshu Lu, Taeghwan Hyeon, Seung Hong Choi, & Dae-Hyeong Kim. Nature Nanotechnology (2016) doi:10.1038/nnano.2016.38 Published online 21 March 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.