An April 30, 2021 news item on Nanowerk announced research from a joint team at Northwestern University (located in Chicago, Illinois, US) and University of Hong Kong of researchers in the field of neuromorphic (brainlike) computing,

Researchers have developed a brain-like computing device that is capable of learning by association.

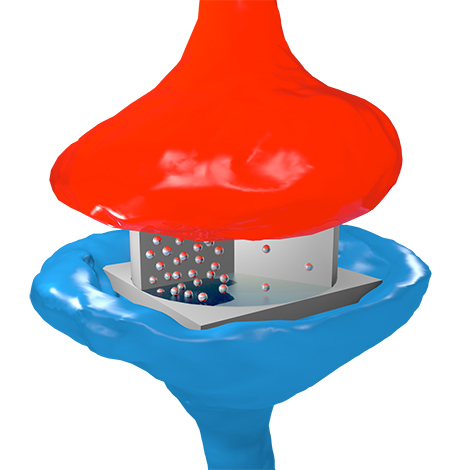

Similar to how famed physiologist Ivan Pavlov conditioned dogs to associate a bell with food, researchers at Northwestern University and the University of Hong Kong successfully conditioned their circuit to associate light with pressure.

…

The device’s secret lies within its novel organic, electrochemical “synaptic transistors,” which simultaneously process and store information just like the human brain. The researchers demonstrated that the transistor can mimic the short-term and long-term plasticity of synapses in the human brain, building on memories to learn over time.

With its brain-like ability, the novel transistor and circuit could potentially overcome the limitations of traditional computing, including their energy-sapping hardware and limited ability to perform multiple tasks at the same time. The brain-like device also has higher fault tolerance, continuing to operate smoothly even when some components fail.

“Although the modern computer is outstanding, the human brain can easily outperform it in some complex and unstructured tasks, such as pattern recognition, motor control and multisensory integration,” said Northwestern’s Jonathan Rivnay, a senior author of the study. “This is thanks to the plasticity of the synapse, which is the basic building block of the brain’s computational power. These synapses enable the brain to work in a highly parallel, fault tolerant and energy-efficient manner. In our work, we demonstrate an organic, plastic transistor that mimics key functions of a biological synapse.”

Rivnay is an assistant professor of biomedical engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering. He co-led the study with Paddy Chan, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at the University of Hong Kong. Xudong Ji, a postdoctoral researcher in Rivnay’s group, is the paper’s first author.

An April 30, 2021 Northwestern University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, includes a good explanation about brainlike computing and information about how synaptic transistors work along with some suggestions for future applications,

Conventional, digital computing systems have separate processing and storage units, causing data-intensive tasks to consume large amounts of energy. Inspired by the combined computing and storage process in the human brain, researchers, in recent years, have sought to develop computers that operate more like the human brain, with arrays of devices that function like a network of neurons.

“The way our current computer systems work is that memory and logic are physically separated,” Ji said. “You perform computation and send that information to a memory unit. Then every time you want to retrieve that information, you have to recall it. If we can bring those two separate functions together, we can save space and save on energy costs.”

Currently, the memory resistor, or “memristor,” is the most well-developed technology that can perform combined processing and memory function, but memristors suffer from energy-costly switching and less biocompatibility. These drawbacks led researchers to the synaptic transistor — especially the organic electrochemical synaptic transistor, which operates with low voltages, continuously tunable memory and high compatibility for biological applications. Still, challenges exist.

“Even high-performing organic electrochemical synaptic transistors require the write operation to be decoupled from the read operation,” Rivnay said. “So if you want to retain memory, you have to disconnect it from the write process, which can further complicate integration into circuits or systems.”

How the synaptic transistor works

To overcome these challenges, the Northwestern and University of Hong Kong team optimized a conductive, plastic material within the organic, electrochemical transistor that can trap ions. In the brain, a synapse is a structure through which a neuron can transmit signals to another neuron, using small molecules called neurotransmitters. In the synaptic transistor, ions behave similarly to neurotransmitters, sending signals between terminals to form an artificial synapse. By retaining stored data from trapped ions, the transistor remembers previous activities, developing long-term plasticity.

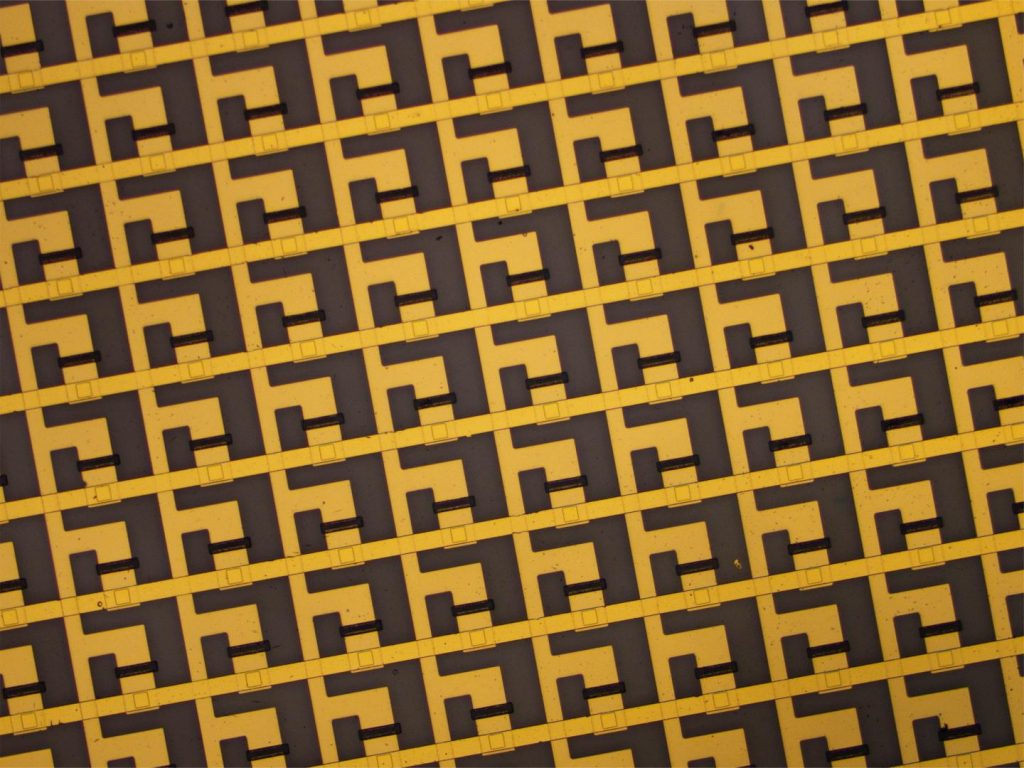

The researchers demonstrated their device’s synaptic behavior by connecting single synaptic transistors into a neuromorphic circuit to simulate associative learning. They integrated pressure and light sensors into the circuit and trained the circuit to associate the two unrelated physical inputs (pressure and light) with one another.

Perhaps the most famous example of associative learning is Pavlov’s dog, which naturally drooled when it encountered food. After conditioning the dog to associate a bell ring with food, the dog also began drooling when it heard the sound of a bell. For the neuromorphic circuit, the researchers activated a voltage by applying pressure with a finger press. To condition the circuit to associate light with pressure, the researchers first applied pulsed light from an LED lightbulb and then immediately applied pressure. In this scenario, the pressure is the food and the light is the bell. The device’s corresponding sensors detected both inputs.

After one training cycle, the circuit made an initial connection between light and pressure. After five training cycles, the circuit significantly associated light with pressure. Light, alone, was able to trigger a signal, or “unconditioned response.”

Future applications

Because the synaptic circuit is made of soft polymers, like a plastic, it can be readily fabricated on flexible sheets and easily integrated into soft, wearable electronics, smart robotics and implantable devices that directly interface with living tissue and even the brain [emphasis mine].

“While our application is a proof of concept, our proposed circuit can be further extended to include more sensory inputs and integrated with other electronics to enable on-site, low-power computation,” Rivnay said. “Because it is compatible with biological environments, the device can directly interface with living tissue, which is critical for next-generation bioelectronics.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Mimicking associative learning using an ion-trapping non-volatile synaptic organic electrochemical transistor by Xudong Ji, Bryan D. Paulsen, Gary K. K. Chik, Ruiheng Wu, Yuyang Yin, Paddy K. L. Chan & Jonathan Rivnay . Nature Communications volume 12, Article number: 2480 (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22680-5 Published: 30 April 2021

This paper is open access.

“… devices that directly interface with living tissue and even the brain,” would I be the only one thinking about cyborgs?