An April 17, 2023 news item on Nanowerk announced research into a graphene cardiac implant/tattoo,

Researchers led by Northwestern University and the University of Texas at Austin (UT) have developed the first cardiac implant made from graphene, a two-dimensional super material with ultra-strong, lightweight and conductive properties.

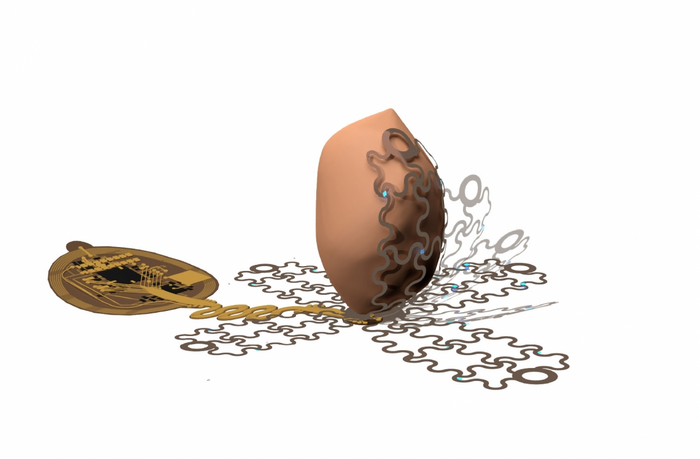

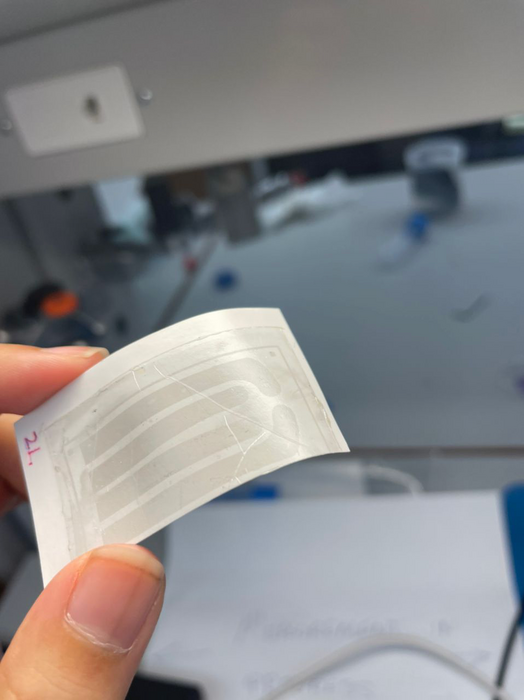

Similar in appearance to a child’s temporary tattoo, the new graphene “tattoo” implant is thinner than a single strand of hair yet still functions like a classical pacemaker. But unlike current pacemakers and implanted defibrillators, which require hard, rigid materials that are mechanically incompatible with the body, the new device softly melds to the heart to simultaneously sense and treat irregular heartbeats. The implant is thin and flexible enough to conform to the heart’s delicate contours as well as stretchy and strong enough to withstand the dynamic motions of a beating heart.

…

An April 17, 2023 Northwestern University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail about the research, graphene, and the difficulties of monitoring a beating heart, Note: Links have been removed,

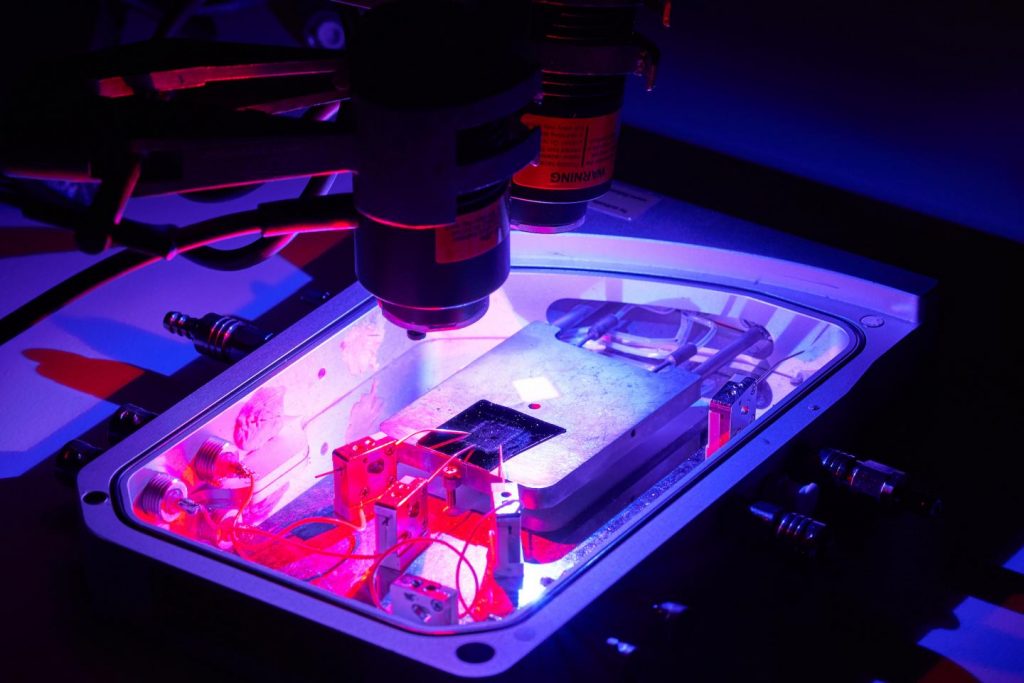

After implanting the device into a rat model, the researchers demonstrated that the graphene tattoo could successfully sense irregular heart rhythms and then deliver electrical stimulation through a series of pulses without constraining or altering the heart’s natural motions. Even better: The technology also is optically transparent, allowing the researchers to use an external source of optical light to record and stimulate the heart through the device.

The study will be published on Thursday (April 20 [2023]) in the journal Advanced Materials. It marks the thinnest known cardiac implant to date.

“One of the challenges for current pacemakers and defibrillators is that they are difficult to affix onto the surface of the heart,” said Northwestern’s Igor Efimov, the study’s senior author. “Defibrillator electrodes, for example, are essentially coils made of very thick wires. These wires are not flexible, and they break. Rigid interfaces with soft tissues, like the heart, can cause various complications. By contrast, our soft, flexible device is not only unobtrusive but also intimately and seamlessly conforms directly onto the heart to deliver more precise measurements.”

An experimental cardiologist, Efimov is a professor of biomedical engineering at Northwestern’s McCormick School of Engineering and professor of medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. He co-led the study with Dmitry Kireev, a research associate at UT. Zexu Lin, a Ph.D. candidate in Efimov’s laboratory, is the paper’s first author.

Miracle material

Known as cardiac arrhythmias, heart rhythm disorders occur when the heart beats either too quickly or too slowly. While some cases of arrhythmia are not serious, many cases can lead to heart failure, stroke and even sudden death. In fact, complications related to arrythmia claim about 300,000 lives annually in the United States. Physicians commonly treat arrhythmia with implantable pacemakers and defibrillators that detect abnormal heartbeats and then correct rhythm with electrical stimulation. While these devices are lifesaving, their rigid nature may constrain the heart’s natural motions, injure soft tissues, cause temporary discomfort and induce complications, such as painful swelling, perforations, blood clots, infection and more.

With these challenges in mind, Efimov and his team sought to develop a bio-compatible device ideal for conforming to soft, dynamic tissues. After reviewing multiple materials, the researchers settled on graphene, an atomically thin form of carbon. With its ultra-strong, lightweight structure and superior conductivity, graphene has potential for many applications in high-performance electronics, high-strength materials and energy devices.

“For bio-compatibility reasons, graphene is particularly attractive,” Efimov said. “Carbon is the basis of life, so it’s a safe material that is already used in different clinical applications. It also is flexible and soft, which works well as an interface between electronics and a soft, mechanically active organ.”

Hitting a beating target

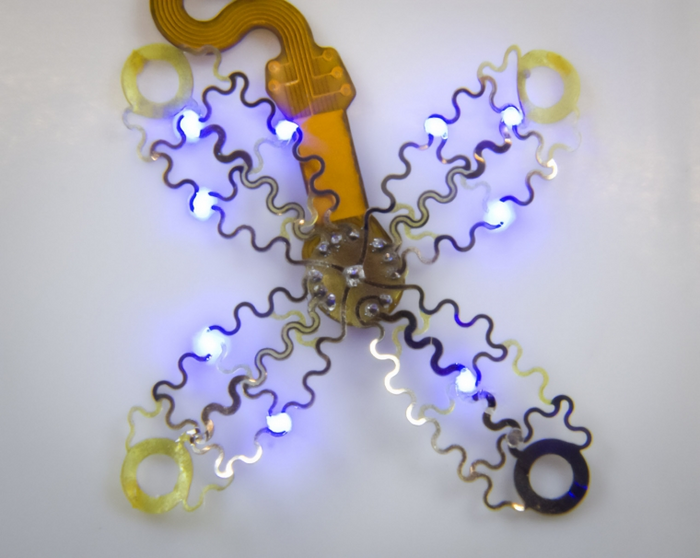

At UT, study co-authors Dimitry Kireev and Deji Akinwande were already developing graphene electronic tattoos (GETs) with sensing capabilities. Flexible and weightless, their team’s e-tattoos adhere to the skin to continuously monitor the body’s vital signs, including blood pressure and the electrical activity of the brain, heart and muscles.

But, while the e-tattoos work well on the skin’s surface, Efimov’s team needed to investigate new methods to use these devices inside the body — directly onto the surface of the heart.

“It’s a completely different application scheme,” Efimov said. “Skin is relatively dry and easily accessible. Obviously, the heart is inside the chest, so it’s difficult to access and in a wet environment.”

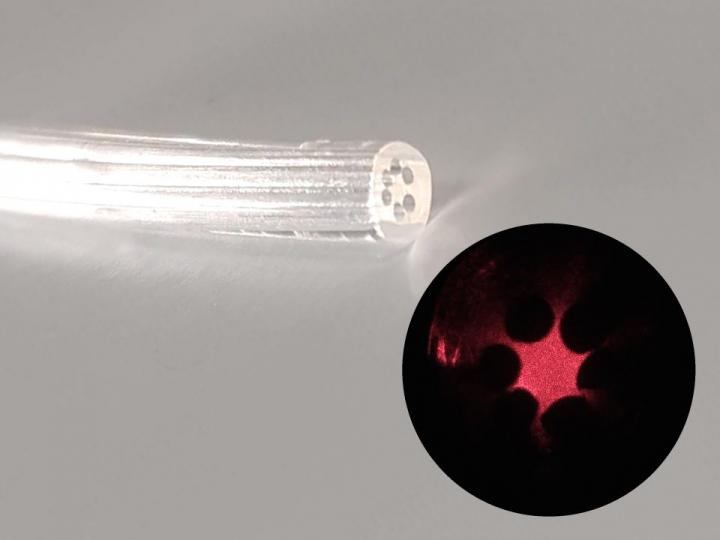

The researchers developed an entirely new technique to encase the graphene tattoo and adhere it to the surface of a beating heart. First, they encapsulated the graphene inside a flexible, elastic silicone membrane — with a hole punched in it to give access to the interior graphene electrode. Then, they gently placed gold tape (with a thickness of 10 microns) onto the encapsulating layer to serve as an electrical interconnect between the graphene and the external electronics used to measure and stimulate the heart. Finally, they placed it onto the heart. The entire thickness of all layers together measures about 100 microns in total.

The resulting device was stable for 60 days on an actively beating heart at body temperature, which is comparable to the duration of temporary pacemakers used as bridges to permanent pacemakers or rhythm management after surgery or other therapies.

Optical opportunities

Leveraging the device’s transparent nature, Efimov and his team performed optocardiography — using light to track and modulate heart rhythm — in the animal study. Not only does this offer a new way to diagnose and treat heart ailments, the approach also opens new possibilities for optogenetics, a method to control and monitor single cells with light.

While electrical stimulation can correct a heart’s abnormal rhythm, optical stimulation is more precise. With light, researchers can track specific enzymes as well as interrogate specific heart, muscle or nerve cells.

“We can essentially combine electrical and optical functions into one biointerface,” Efimov said. “Because graphene is optically transparent, we can actually read through it, which gives us a much higher density of readout.”

…

The University of Texas at Austin issued an April 18, 2023 news release and as you would expect the focus is on their researchers, Note 1: I’ve removed many but not all of the redundancies between the two news releases; Note 2: A link has been removed,

A new cardiac implant made from graphene, a two-dimensional super material with ultra-strong, lightweight and conductive properties, functions like a classic pacemaker with some major improvements.

A team led by researchers from The University of Texas at Austin and Northwestern University developed the implantable derivative from wearable graphene-based electronic tattoo, or e-tattoo – graphene biointerface. The device, detailed in the journal Advanced Materials, marks the thinnest known cardiac implant to date.

“It’s very exciting to take our e-tattoo technology and use it as an implantable device inside the body,” said Dmitry Kireev, a postdoctoral research associate in the lab of professor Deji Akinwande’s lab at UT Austin who co-led the research. “The fact that is much more compatible with the human body, lightweight, and transparent, makes this a more natural solution for people dealing with heart problems.”

…

Hitting a beating target

At UT Austin, Akinwande and his team had been developing e-tattoos using graphene for several years, with a variety of functions, including monitoring body signals. Flexible and weightless, their team’s e-tattoos adhere to the skin to continuously monitor the body’s vital signs, including blood pressure and the electrical activity of the brain, heart and muscles.

But, while the e-tattoos work well on the skin’s surface, the researchers needed to find new ways to deploy these devices inside the body — directly onto the surface of the heart.

“The conditions inside the body are very different compared to affixing a device to the skin, so we had to re-imagine how we package our e-tattoo technology,” said Akinwande, a professor in the Chandra Family Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering.

The researchers developed an entirely new technique to encase the graphene tattoo and adhere it to the surface of a beating heart. …

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Graphene Biointerface for Cardiac Arrhythmia Diagnosis and Treatment by Zexu Lin, Dmitry Kireev, Ning Liu, Shubham Gupta, Jessica LaPiano, Sofian N. Obaid, Zhiyuan Chen, Deji Akinwande, Igor R. Efimov. Advanced Materials Volume 35, Issue 22 June 1, 2023 2212190 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1002/adma.202212190 First published online: 25 March 2023

This paper is open access.