An April 26, 2022 news item on phys.org caught my eye with its mention of nanocellulose, trees, and electronics,

Electronics can grow on trees thanks to nanocellulose paper semiconductors

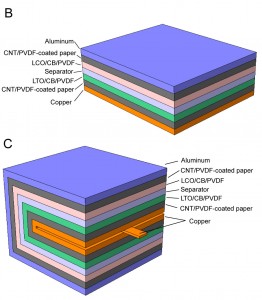

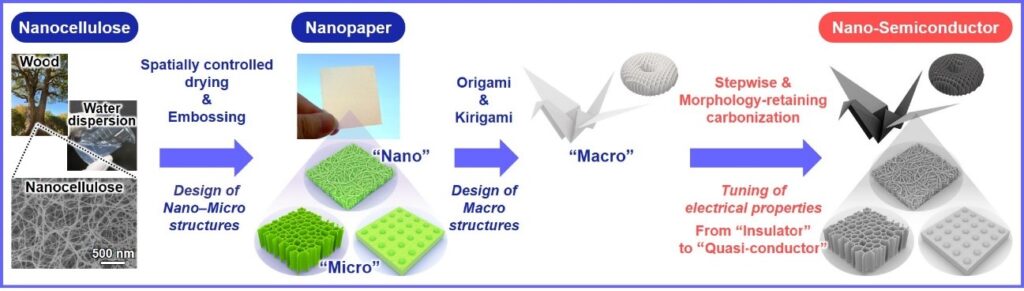

Semiconducting nanomaterials with 3D network structures have high surface areas and a lot of pores that make them excellent for applications involving adsorbing, separating, and sensing. However, simultaneously controlling the electrical properties and creating useful micro- and macro-scale structures, while achieving excellent functionality and end-use versatility, remains challenging. Now, Osaka University researchers, in collaboration with The University of Tokyo, Kyushu University, and Okayama University, have developed a nanocellulose paper semiconductor that provides both nano−micro−macro trans-scale designability of the 3D structures and wide tunability of the electrical properties. Their findings are published in ACS Nano.

Cellulose is a natural and easy to source material derived from wood. Cellulose nanofibers (nanocellulose) can be made into sheets of flexible nanocellulose paper (nanopaper) with dimensions like those of standard A4. Nanopaper does not conduct an electric current; however, heating can introduce conducting properties. Unfortunately, this exposure to heat can also disrupt the nanostructure.

The researchers have therefore devised a treatment process that allows them to heat the nanopaper without damaging the structures of the paper from the nanoscale up to the macroscale.

…

An April 28, 2022 Osaka University news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail about the work

“An important property for the nanopaper semiconductor is tunability because this allows devices to be designed for specific applications,” explains study author Hirotaka Koga. “We applied an iodine treatment that was very effective for protecting the nanostructure of the nanopaper. Combining this with spatially controlled drying meant that the pyrolysis treatment did not substantially alter the designed structures and the selected temperature could be used to control the electrical properties.”

The researchers used origami (paper folding) and kirigami (paper cutting) techniques to provide playful examples of the flexibility of the nanopaper at the macrolevel. A bird and box were folded, shapes including an apple and snowflake were punched out, and more intricate structures were produced by laser cutting. This demonstrated the level of detail possible, as well as the lack of damage caused by the heat treatment.

Examples of successful applications showed nanopaper semiconductor sensors incorporated into wearable devices to detect exhaled moisture breaking through facemasks and moisture on the skin. The nanopaper semiconductor was also used as an electrode in a glucose biofuel cell and the energy generated lit a small bulb.

“The structure maintenance and tunability that we have been able to show is very encouraging for the translation of nanomaterials into practical devices,” says Associate Professor Koga. “We believe that our approach will underpin the next steps in sustainable electronics made entirely from plant materials.”

…

About Osaka University

Osaka University was founded in 1931 as one of the seven imperial universities of Japan and is now one of Japan’s leading comprehensive universities with a broad disciplinary spectrum. This strength is coupled with a singular drive for innovation that extends throughout the scientific process, from fundamental research to the creation of applied technology with positive economic impacts. Its commitment to innovation has been recognized in Japan and around the world, being named Japan’s most innovative university in 2015 (Reuters 2015 Top 100) and one of the most innovative institutions in the world in 2017 (Innovative Universities and the Nature Index Innovation 2017). Now, Osaka University is leveraging its role as a Designated National University Corporation selected by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology to contribute to innovation for human welfare, sustainable development of society, and social transformation.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Nanocellulose Paper Semiconductor with a 3D Network Structure and Its Nano–Micro–Macro Trans-Scale Design by Hirotaka Koga, Kazuki Nagashima, Koichi Suematsu, Tsunaki Takahashi, Luting Zhu, Daiki Fukushima, Yintong Huang, Ryo Nakagawa, Jiangyang Liu, Kojiro Uetani, Masaya Nogi, Takeshi Yanagida, and Yuta Nishina. ACS Nano 2022, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.1c10728 Publication Date:April 26, 2022 © 2022 The Authors. Published by American Chemical Society

The paper appears to be open access.