To my imaginary AI friend

Dear friend,

I thought you might be amused by these Roomba-like* paintbots at the Vancouver Art Gallery’s (VAG) latest exhibition, “The Imitation Game: Visual Culture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence” (March 5, 2022 – October 23, 2022).

*A Roomba is a robot vacuum cleaner produced and sold by iRobot.

As far as I know, this is the Vancouver Art Gallery’s first art/science or art/technology exhibit and it is an alternately fascinating, exciting, and frustrating take on artificial intelligence and its impact on the visual arts. Curated by Bruce Grenville, VAG Senior Curator, and Glenn Entis, Guest Curator, the show features 20 ‘objects’ designed to both introduce viewers to the ‘imitation game’ and to challenge them. From the VAG Imitation Game webpage,

The Imitation Game surveys the extraordinary uses (and abuses) of artificial intelligence (AI) in the production of modern and contemporary visual culture around the world. The exhibition follows a chronological narrative that first examines the development of artificial intelligence, from the 1950s to the present [emphasis mine], through a precise historical lens. Building on this foundation, it emphasizes the explosive growth of AI across disciplines, including animation, architecture, art, fashion, graphic design, urban design and video games, over the past decade. Revolving around the important roles of machine learning and computer vision in AI research and experimentation, The Imitation Game reveals the complex nature of this new tool and demonstrates its importance for cultural production.

…

And now …

As you’ve probably guessed, my friend, you’ll find a combination of both background information and commentary on the show.

I’ve initially focused on two people (a scientist and a mathematician) who were seminal thinkers about machines, intelligence, creativity, and humanity. I’ve also provided some information about the curators, which hopefully gives you some insight into the show.

As for the show itself, you’ll find a few of the ‘objects’ highlighted with one of them being investigated at more length. The curators devoted some of the show to ethical and social justice issues, accordingly, the Vancouver Art Gallery hosted the University of British Columbia’s “Speculative Futures: Artificial Intelligence Symposium” on April 7, 2022,

Presented in conjunction with the exhibition The Imitation Game: Visual Culture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, the Speculative Futures Symposium examines artificial intelligence and the specific uses of technology in its multifarious dimensions. Across four different panel conversations, leading thinkers of today will explore the ethical implications of technology and discuss how they are working to address these issues in cultural production.”

So, you’ll find more on these topics here too.

And for anyone else reading this (not you, my friend who is ‘strong’ AI and not similar to the ‘weak’ AI found in this show), there is a description of ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ AI on the avtsim.com/weak-ai-strong-ai webpage, Note: A link has been removed,

There are two types of AI: weak AI and strong AI.

Weak, sometimes called narrow, AI is less intelligent as it cannot work without human interaction and focuses on a more narrow, specific, or niched purpose. …

Strong AI on the other hand is in fact comparable to the fictitious AIs we see in media like the terminator. The theoretical Strong AI would be equivalent or greater to human intelligence.

….

My dear friend, I hope you will enjoy.

The Imitation Game and ‘mad, bad, and dangerous to know’

In some circles, it’s better known as ‘The Turing Test;” the Vancouver Art Gallery’s ‘Imitation Game’ hosts a copy of Alan Turing’s foundational paper for establishing whether artificial intelligence is possible (I thought this was pretty exciting).

Here’s more from The Turing Test essay by Graham Oppy and David Dowe for the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy,

The phrase “The Turing Test” is most properly used to refer to a proposal made by Turing (1950) as a way of dealing with the question whether machines can think. According to Turing, the question whether machines can think is itself “too meaningless” to deserve discussion (442). However, if we consider the more precise—and somehow related—question whether a digital computer can do well in a certain kind of game that Turing describes (“The Imitation Game”), then—at least in Turing’s eyes—we do have a question that admits of precise discussion. Moreover, as we shall see, Turing himself thought that it would not be too long before we did have digital computers that could “do well” in the Imitation Game.

The phrase “The Turing Test” is sometimes used more generally to refer to some kinds of behavioural tests for the presence of mind, or thought, or intelligence in putatively minded entities. …

Next to the display holding Turing’s paper, is another display with an excerpt of an explanation from Turing about how he believed Ada Lovelace would have responded to the idea that machines could think based on a copy of some of her writing (also on display). She proposed that creativity, not thinking, is what set people apart from machines. (See the April 17, 2020 article “Thinking Machines? Has the Lovelace Test Been Passed?’ on mindmatters.ai.)

It’s like a dialogue between two seminal thinkers who lived about 100 years apart; Lovelace, born in 1815 and dead in 1852, and Turing, born in 1912 and dead in 1954. Both have fascinating back stories (more about those later) and both played roles in how computers and artificial intelligence are viewed.

Adding some interest to this walk down memory lane is a 3rd display, an illustration of the ‘Mechanical Turk‘, a chess playing machine that made the rounds in Europe from 1770 until it was destroyed in 1854. A hoax that fooled people for quite a while it is a reminder that we’ve been interested in intelligent machines for centuries. (Friend, Turing and Lovelace and the Mechanical Turk are found in Pod 1.)

Back story: Turing and the apple

Turing is credited with being instrumental in breaking the German ENIGMA code during World War II and helping to end the war. I find it odd that he ended up at the University of Manchester in the post-war years. One would expect him to have been at Oxford or Cambridge. At any rate, he died in 1954 of cyanide poisoning two years after he was arrested for being homosexual and convicted of indecency. Given the choice of incarceration or chemical castration, he chose the latter. There is, to this day, debate about whether or not it was suicide. Here’s how his death is described in this Wikipedia entry (Note: Links have been removed),

On 8 June 1954, at his house at 43 Adlington Road, Wilmslow,[150] Turing’s housekeeper found him dead. He had died the previous day at the age of 41. Cyanide poisoning was established as the cause of death.[151] When his body was discovered, an apple lay half-eaten beside his bed, and although the apple was not tested for cyanide,[152] it was speculated that this was the means by which Turing had consumed a fatal dose. An inquest determined that he had committed suicide. Andrew Hodges and another biographer, David Leavitt, have both speculated that Turing was re-enacting a scene from the Walt Disney film Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937), his favourite fairy tale. Both men noted that (in Leavitt’s words) he took “an especially keen pleasure in the scene where the Wicked Queen immerses her apple in the poisonous brew”.[153] Turing’s remains were cremated at Woking Crematorium on 12 June 1954,[154] and his ashes were scattered in the gardens of the crematorium, just as his father’s had been.[155]

Philosopher Jack Copeland has questioned various aspects of the coroner’s historical verdict. He suggested an alternative explanation for the cause of Turing’s death: the accidental inhalation of cyanide fumes from an apparatus used to electroplate gold onto spoons. The potassium cyanide was used to dissolve the gold. Turing had such an apparatus set up in his tiny spare room. Copeland noted that the autopsy findings were more consistent with inhalation than with ingestion of the poison. Turing also habitually ate an apple before going to bed, and it was not unusual for the apple to be discarded half-eaten.[156] Furthermore, Turing had reportedly borne his legal setbacks and hormone treatment (which had been discontinued a year previously) “with good humour” and had shown no sign of despondency prior to his death. He even set down a list of tasks that he intended to complete upon returning to his office after the holiday weekend.[156] Turing’s mother believed that the ingestion was accidental, resulting from her son’s careless storage of laboratory chemicals.[157] Biographer Andrew Hodges theorised that Turing arranged the delivery of the equipment to deliberately allow his mother plausible deniability with regard to any suicide claims.[158]

…

The US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) also has an entry for Alan Turing dated April 10, 2015 it’s titled, The Enigma of Alan Turing.

Back story: Ada Byron Lovelace, the 2nd generation of ‘mad, bad, and dangerous to know’

A mathematician and genius in her own right, Ada Lovelace’s father George Gordon Byron, better known as the poet Lord Byron, was notoriously described as ‘mad, bad, and dangerous to know’.

Lovelace too could have been been ‘mad, bad, …’ but she is described less memorably as “… manipulative and aggressive, a drug addict, a gambler and an adulteress, …” as mentioned in my October 13, 20215 posting. It marked the 200th anniversary of her birth, which was celebrated with a British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) documentary and an exhibit at the Science Museum in London, UK.

She belongs in the Vancouver Art Gallery’s show along with Alan Turing due to her prediction that computers could be made to create music. She also published the first computer program. Her feat is astonishing when you know only one working model {1/7th of the proposed final size) of a computer was ever produced. (The machine invented by Charles Babbage was known as a difference engine. You can find out more about the Difference engine on Wikipedia and about Babbage’s proposed second invention, the Analytical engine.)

(Byron had almost nothing to do with his daughter although his reputation seems to have dogged her. You can find out more about Lord Byron here.)

AI and visual culture at the VAG: the curators

As mentioned earlier, the VAG’s “The Imitation Game: Visual Culture in the Age of Artificial Intelligence” show runs from March 5, 2022 – October 23, 2022. Twice now, I have been to this weirdly exciting and frustrating show.

Bruce Grenville, VAG Chief/Senior Curator, seems to specialize in pulling together diverse materials to illustrate ‘big’ topics. His profile for Emily Carr University of Art + Design (where Grenville teaches) mentions these shows ,

… He has organized many thematic group exhibitions including, MashUp: The Birth of Modern Culture [emphasis mine], a massive survey documenting the emergence of a mode of creativity that materialized in the late 1800s and has grown to become the dominant model of cultural production in the 21st century; KRAZY! The Delirious World [emphasis mine] of Anime + Manga + Video Games + Art, a timely and important survey of modern and contemporary visual culture from around the world; Home and Away: Crossing Cultures on the Pacific Rim [emphasis mine] a look at the work of six artists from Vancouver, Beijing, Ho Chi Minh City, Seoul and Los Angeles, who share a history of emigration and diaspora. …

Glenn Entis, Guest Curator and founding faculty member of Vancouver’s Centre for Digital Media (CDM) is Grenville’s co-curator, from Entis’ CDM profile,

“… an Academy Award-winning animation pioneer and games industry veteran. The former CEO of Dreamworks Interactive, Glenn worked with Steven Spielberg and Jeffrey Katzenberg on a number of video games …,”

Steve Newton in his March 4, 2022 preview does a good job of describing the show although I strongly disagree with the title of his article which proclaims “The Vancouver Art Gallery takes a deep dive into artificial intelligence with The Imitation Game.” I think it’s more of a shallow dive meant to cover more distance than depth,

… The exhibition kicks off with an interactive introduction inviting visitors to actively identify diverse areas of cultural production influenced by AI.

“That was actually one of the pieces that we produced in collaboration with the Centre for Digital Media,” Grenville notes, “so we worked with some graduate-student teams that had actually helped us to design that software. It was the beginning of COVID when we started to design this, so we actually wanted a no-touch interactive. So, really, the idea was to say, ‘Okay, this is the very entrance to the exhibition, and artificial intelligence, this is something I’ve heard about, but I’m not really sure how it’s utilized in ways. But maybe I know something about architecture; maybe I know something about video games; maybe I know something about the history of film.

“So you point to these 10 categories of visual culture [emphasis mine]–video games, architecture, fashion design, graphic design, industrial design, urban design–so you point to one of those, and you might point to ‘film’, and then when you point at it that opens up into five different examples of what’s in the show, so it could be 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Bladerunner, or World on a Wire.”

After the exhibition’s introduction—which Grenville equates to “opening the door to your curiosity” about artificial intelligence–visitors encounter one of its main categories, Objects of Wonder, which speaks to the history of AI and the critical advances the technology has made over the years.

“So there are 20 Objects of Wonder [emphasis mine],” Grenville says, “which go from 1949 to 2022, and they kind of plot out the history of artificial intelligence over that period of time, focusing on a specific object. Like [mathematician and philosopher] Norbert Wiener made this cybernetic creature, he called it a ‘Moth’, in 1949. So there’s a section that looks at this idea of kind of using animals–well, machine animals–and thinking about cybernetics, this idea of communication as feedback, early thinking around neuroscience and how neuroscience starts to imagine this idea of a thinking machine.

…

And there’s this from Newton’s March 4, 2022 preview,

“It’s interesting,” Grenville ponders, “artificial intelligence is virtually unregulated. [emphasis mine] You know, if you think about the regulatory bodies that govern TV or radio or all the types of telecommunications, there’s no equivalent for artificial intelligence, which really doesn’t make any sense. And so what happens is, sometimes with the best intentions [emphasis mine]—sometimes not with the best intentions—choices are made about how artificial intelligence develops. So one of the big ones is facial-recognition software [emphasis mine], and any body-detection software that’s being utilized.

In addition to it being the best overview of the show I’ve seen so far, this is the only one where you get a little insight into what the curators were thinking when they were developing it.

A deep dive into AI?

it was only while searching for a little information before the show that I realized I don’t have any definitions for artificial intelligence! What is AI? Sadly, there are no definitions of AI in the exhibit.

It seems even experts don’t have a good definition. Take a look at this,

The definition of AI is fluid [emphasis mine] and reflects a constantly shifting landscape marked by technological advancements and growing areas of application. Indeed, it has frequently been observed that once AI becomes capable of solving a particular problem or accomplishing a certain task, it is often no longer considered to be “real” intelligence [emphasis mine] (Haenlein & Kaplan, 2019). A firm definition was not applied for this report [emphasis mine], given the variety of implementations described above. However, for the purposes of deliberation, the Panel chose to interpret AI as a collection of statistical and software techniques, as well as the associated data and the social context in which they evolve — this allows for a broader and more inclusive interpretation of AI technologies and forms of agency. The Panel uses the term AI interchangeably to describe various implementations of machine-assisted design and discovery, including those based on machine learning, deep learning, and reinforcement learning, except for specific examples where the choice of implementation is salient. [p. 6 print version; p. 34 PDF version]

The above is from the Leaps and Boundaries report released May 10, 2022 by the Council of Canadian Academies’ Expert Panel on Artificial Intelligence for Science and Engineering.

Sometimes a show will take you in an unexpected direction. I feel a lot better ‘not knowing’. Still, I wish the curators had acknowledged somewhere in the show that artificial intelligence is a slippery concept. Especially when you add in robots and automatons. (more about them later)

21st century technology in a 19th/20th century building

Just barely making it into the 20th century, the building where the Vancouver Art Gallery currently resides was for many years the provincial courthouse (1911 – 1978). In some ways, it’s a disconcerting setting for this show.

They’ve done their best to make the upstairs where the exhibit is displayed look like today’s galleries with their ‘white cube aesthetic’ and strong resemblance to the scientific laboratories seen in movies.

(For more about the dominance, since the 1930s, of the ‘white cube aesthetic’ in art galleries around the world, see my July 26, 2021 posting; scroll down about 50% of the way.)

It makes for an interesting tension, the contrast between the grand staircase, the cupola, and other architectural elements and the sterile, ‘laboratory’ environment of the modern art gallery.

20 Objects of Wonder and the flow of the show

It was flummoxing. Where are the 20 objects? Why does it feel like a maze in a laboratory? Loved the bees, but why? Eeeek Creepers! What is visual culture anyway? Where am I?

The objects of the show

It turns out that the curators have a more refined concept for ‘object’ than I do. There weren’t 20 material objects, there were 20 numbered ‘pods’ with perhaps a screen or a couple of screens or a screen and a material object or two illustrating the pod’s topic.

Looking up a definition for the word (accessed from a June 9, 2022 duckduckgo.com search). yielded this, (the second one seems à propos),

objectŏb′jĭkt, -jĕkt″

noun

1. Something perceptible by one or more of the senses, especially by vision or touch; a material thing.

2. A focus of attention, feeling, thought, or action.

3. A limiting factor that must be considered.

The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, 5th Edition.

Each pod = a focus of attention.

The show’s flow is a maze. Am I a rat?

The pods are defined by a number and by temporary walls. So if you look up, you’ll see a number and a space partly enclosed by a temporary wall or two.

It’s a very choppy experience. For example, one minute you can be in pod 1 and, when you turn the corner, you’re in pod 4 or 5 or ? There are pods I’ve not seen, despite my two visits, because I kept losing my way. This led to an existential crisis on my second visit. “Had I missed the greater meaning of this show? Was there some sort of logic to how it was organized? Was there meaning to my life? Was I a rat being nudged around in a maze?” I didn’t know.

Thankfully, I have since recovered. But, I will return to my existential crisis later, with a special mention for “Creepers.”

The fascinating

My friend, you know I appreciated the history and in addition to Alan Turing, Ada Lovelace and the Mechanical Turk, at the beginning of the show, they included a reference to Ovid (or Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō), a Roman poet who lived from 43 BCE – 17/18 CE in one of the double digit (17? or 10? or …) in one of the pods featuring a robot on screen. As to why Ovid might be included, this excerpt from a February 12, 2018 posting on the cosmolocal.org website provides a clue (Note. Links have been removed),

The University of King’s College [Halifax, Nova Scotia] presents Automatons! From Ovid to AI, a nine-lecture series examining the history, issues and relationships between humans, robots, and artificial intelligence [emphasis mine]. The series runs from January 10 to April 4 [2018], and features leading scholars, performers and critics from Canada, the US and Britain.

“Drawing from theatre, literature, art, science and philosophy, our 2018 King’s College Lecture Series features leading international authorities exploring our intimate relationships with machines,” says Dr. Gordon McOuat, professor in the King’s History of Science and Technology (HOST) and Contemporary Studies Programs.

…

“From the myths of Ovid [emphasis mine] and the automatons [emphasis mine] of the early modern period to the rise of robots, cyborgs, AI and artificial living things in the modern world, the 2018 King’s College Lecture Series examines the historical, cultural, scientific and philosophical place of automatons in our lives—and our future,” adds McOuat.

…

I loved the way the curators managed to integrate the historical roots for artificial intelligence and, by extension, the world of automatons, robots, cyborgs, and androids. Yes, starting the show with Alan Turing and Ada Lovelace could be expected but Norbert Wiener’s Moth (1949) acts as a sort of preview for Sougwen Chung’s “Omnia per Omnia, 2018” (GIF seen at the beginning of this post). Take a look for yourself (from the cyberneticzoo.com September 19, 2009 posting by cyberne1. Do you see the similarity or am I the only one?

Sculpture

This is the first time I’ve come across an AI/sculpture project. The VAG show features Scott Eaton’s sculptures on screens in a room devoted to his work.

This looks like an image of a piece of ginger root and It’s fascinating to watch the process as the AI agent ‘evolves’ Eaton’s drawings into onscreen sculptures. It would have enhanced the experience if at least one of Eaton’s ‘evolved’ and physically realized sculptures had been present in the room but perhaps there were financial and/or logistical reasons for the absence.

Both Chung and Eaton are collaborating with an AI agent. In Chung’s case the AI is integrated into the paintbots with which she interacts and paints alongside and in Eaton’s case, it’s via a computer screen. In both cases, the work is mildly hypnotizing in a way that reminds me of lava lamps.

One last note about Chung and her work. She was one of the artists invited to present new work at an invite-only April 22, 2022 Embodied Futures workshop at the “What will life become?” event held by the Berrgruen Institute and the University of Southern California (USC),

Embodied Futures invites participants to imagine novel forms of life, mind, and being through artistic and intellectual provocations on April 22 [2022].

Beginning at 1 p.m., together we will experience the launch of five artworks commissioned by the Berggruen Institute. We asked these artists: How does your work inflect how we think about “the human” in relation to alternative “embodiments” such as machines, AIs, plants, animals, the planet, and possible alien life forms in the cosmos? [emphases mine] Later in the afternoon, we will take provocations generated by the morning’s panels and the art premieres in small breakout groups that will sketch futures worlds, and lively entities that might dwell there, in 2049.

…

This leads to (and my friend, while I too am taking a shallow dive, for this bit I’m going a little deeper):

Bees and architecture

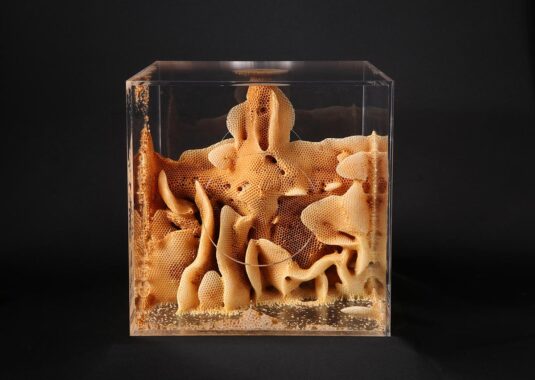

Neri Oxman’s contribution (Golden Bee Cube, Synthetic Apiary II [2020]) is an exhibit featuring three honeycomb structures and a video featuring the bees in her synthetic apiary.

Neri Oxman (then a faculty member of the Mediated Matter Group at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology) described the basis for the first and all other iterations of her synthetic apiary in Patrick Lynch’s October 5, 2016 article for ‘ArchDaily; Broadcasting Architecture Worldwide’, Note: Links have been removed,

Designer and architect Neri Oxman and the Mediated Matter group have announced their latest design project: the Synthetic Apiary. Aimed at combating the massive bee colony losses that have occurred in recent years, the Synthetic Apiary explores the possibility of constructing controlled, indoor environments that would allow honeybee populations to thrive year-round.

…

“It is time that the inclusion of apiaries—natural or synthetic—for this “keystone species” be considered a basic requirement of any sustainability program,” says Oxman.

In developing the Synthetic Apiary, Mediated Matter studied the habits and needs of honeybees, determining the precise amounts of light, humidity and temperature required to simulate a perpetual spring environment. [emphasis mine] They then engineered an undisturbed space where bees are provided with synthetic pollen and sugared water and could be evaluated regularly for health.

…

In the initial experiment, the honeybees’ natural cycle proved to adapt to the new environment, as the Queen was able to successfully lay eggs in the apiary. The bees showed the ability to function normally in the environment, suggesting that natural cultivation in artificial spaces may be possible across scales, “from organism- to building-scale.”

“At the core of this project is the creation of an entirely synthetic environment enabling controlled, large-scale investigations of hives,” explain the designers.

…

Mediated Matter chose to research into honeybees not just because of their recent loss of habitat, but also because of their ability to work together to create their own architecture, [emphasis mine] a topic the group has explored in their ongoing research on biologically augmented digital fabrication, including employing silkworms to create objects and environments at product, architectural, and possibly urban, scales.

“The Synthetic Apiary bridges the organism- and building-scale by exploring a “keystone species”: bees. Many insect communities present collective behavior known as “swarming,” prioritizing group over individual survival, while constantly working to achieve common goals. Often, groups of these eusocial organisms leverage collaborative behavior for relatively large-scale construction. For example, ants create extremely complex networks by tunneling, wasps generate intricate paper nests with materials sourced from local areas, and bees deposit wax to build intricate hive structures.”

…

This January 19, 2022 article by Crown Honey for its eponymous blog updates Oxman’s work (Note 1: All emphases are mine; Note 2: A link has been removed),

…

Synthetic Apiary II investigates co-fabrication between humans and honey bees through the use of designed environments in which Apis mellifera colonies construct comb. These designed environments serve as a means by which to convey information to the colony. The comb that the bees construct within these environments comprises their response to the input information, enabling a form of communication through which we can begin to understand the hive’s collective actions from their perspective.

Some environments are embedded with chemical cues created through a novel pheromone 3D-printing process, while others generate magnetic fields of varying strength and direction. Others still contain geometries of varying complexity or designs that alter their form over time.

When offered wax augmented with synthetic biomarkers, bees appear to readily incorporate it into their construction process, likely due to the high energy cost of producing fresh wax. This suggests that comb construction is a responsive and dynamic process involving complex adaptations to perturbations from environmental stimuli, not merely a set of predefined behaviors building toward specific constructed forms. Each environment therefore acts as a signal that can be sent to the colony to initiate a process of co-fabrication.

Characterization of constructed comb morphology generally involves visual observation and physical measurements of structural features—methods which are limited in scale of analysis and blind to internal architecture. In contrast, the wax structures built by the colonies in Synthetic Apiary II are analyzed through high-throughput X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans that enable a more holistic digital reconstruction of the hive’s structure.

Geometric analysis of these forms provides information about the hive’s design process, preferences, and limitations when tied to the inputs, and thereby yields insights into the invisible mediations between bees and their environment.

Developing computational tools to learn from bees can facilitate the very beginnings of a dialogue with them. Refined by evolution over hundreds of thousands of years, their comb-building behaviors and social organizations may reveal new forms and methods of formation that can be applied across our human endeavors in architecture, design, engineering, and culture.Further, with a basic understanding and language established, methods of co-fabrication together with bees may be developed, enabling the use of new biocompatible materials and the creation of more efficient structural geometries that modern technology alone cannot achieve.

In this way, we also move our built environment toward a more synergistic embodiment, able to be more seamlessly integrated into natural environments through material and form, even providing habitats of benefit to both humans and nonhumans. It is essential to our mutual survival for us to not only protect but moreover to empower these critical pollinators – whose intrinsic behaviors and ecosystems we have altered through our industrial processes and practices of human-centric design – to thrive without human intervention once again.

In order to design our way out of the environmental crisis that we ourselves created, we must first learn to speak nature’s language. …

The three (natural, gold nanoparticle, and silver nanoparticle) honeycombs in the exhibit are among the few physical objects (the others being the historical documents and the paintbots with their canvasses) in the show and it’s almost a relief after the parade of screens. It’s the accompanying video that’s eerie. Everything is in white, as befits a science laboratory, in this synthetic apiary where bees are fed sugar water and fooled into a spring that is eternal.

(You may want to check out Lynch’s October 5, 2016 article or Crown Honey’s January 19, 2022 article as both have embedded images and the Lynch article includes a Synthetic Apiary video. The image above is a still from the video.)

As I asked a friend, where are the flowers? Ron Miksha, a bee ecologist working at the University of Calgary, details some of the problems with Oxman’s Synthetic Apiary this way in his October 7, 2016 posting on his Bad Beekeeping Blog,

In a practical sense, the synthetic apiary fails on many fronts: Bees will survive a few months on concoctions of sugar syrup and substitute pollen, but they need a natural variety of amino acids and minerals to actually thrive. They need propolis and floral pollen. They need a ceiling 100 metres high and a 2-kilometre hallway if drone and queen will mate, or they’ll die after the old queen dies. They need an artificial sun that travels across the sky, otherwise, the bees will be attracted to artificial lights and won’t return to their hive. They need flowery meadows, fresh water, open skies. [emphasis mine] They need a better holodeck.

Dorothy Woodend’s March 10, 2022 review of the VAG show for The Tyee poses other issues with the bees and the honeycombs,

…

When AI messes about with other species, there is something even more unsettling about the process. American-Israeli artist Neri Oxman’s Golden Bee Cube, Synthetic Apiary II, 2020 uses real bees who are proffered silver and gold [nanoparticles] to create their comb structures. While the resulting hives are indeed beautiful, rendered in shades of burnished metal, there is a quality of unease imbued in them. Is the piece akin to apiary torture chambers? I wonder how the bees feel about this collaboration and whether they’d like to renegotiate the deal.

…

There’s no question the honeycombs are fascinating and disturbing but I don’t understand how artificial intelligence was a key factor in either version of Oxman’s synthetic apiary. In the 2022 article by Crown Honey, there’s this “Developing computational tools to learn from bees can facilitate the very beginnings of a dialogue with them [honeybees].” It’s probable that the computational tools being referenced include AI and the Crown Honey article seems to suggest those computational tools are being used to analyze the bees behaviour after the fact.

Yes, I can imagine a future where ‘strong’ AI (such as you, my friend) is in ‘dialogue’ with the bees and making suggestions and running the experiments but it’s not clear that this is the case currently. The Oxman exhibit contribution would seem to be about the future and its possibilities whereas many of the other ‘objects’ concern the past and/or the present.

Friend, let’s take a break, shall we? Part 2 is coming up.