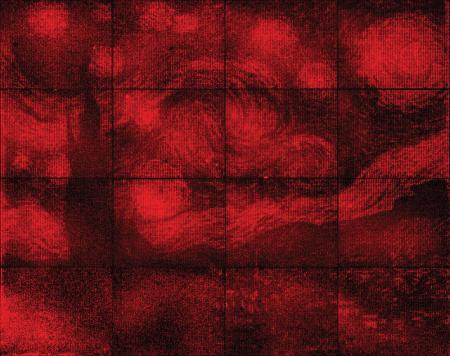

This glowing reproduction of “The Starry Night” contains 65,536 pixels and is the width of a dime across.

Credit: Ashwin Gopinath/Caltech

It may take you a few seconds (it did me) but it’s possible to see Van Gogh’s Starry Night in this image. A July 12, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily reveals more,

Using folded DNA [deoxyribonucleic acid] to precisely place glowing molecules within microscopic light resonators, researchers at Caltech have created one of the world’s smallest reproductions of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night.

A July 12, 2016 Caltech news release (also on EurekAlert) by Richard Perkins, which originated the news item, provides more information about the image, DNA origami, and this latest research on coupling light emitters to photonic crystal cavities (Note: Links have been removed),

The monochrome image—just the width of a dime across—was a proof-of-concept project that demonstrated, for the first time, how the precision placement of DNA origami can be used to build chip-based devices like computer circuits at smaller scales than ever before.

DNA origami, developed 10 years ago by Caltech’s Paul Rothemund (BS ’94), is a technique that allows researchers to fold a long strand of DNA into any desired shape. The folded DNA then acts as a scaffold onto which researchers can attach and organize all kinds of nanometer-scale components, from fluorescent molecules to electrically conductive carbon nanotubes to drugs.

“Think of it a bit like the pegboards people use to organize tools in their garages, only in this case, the pegboard assembles itself from DNA strands and the tools likewise find their own positions,” says Rothemund, research professor of bioengineering, computing and mathematical sciences, and computation and neural systems. “It all happens in a test tube without human intervention, which is important because all of the parts are too small to manipulate efficiently, and we want to make billions of devices.”

The process has the potential to influence a variety of applications from drug delivery to the construction of nanoscale computers. But for many applications, organizing nanoscale components to create devices on DNA pegboards is not enough; the devices have to be wired together into larger circuits and need to have a way of communicating with larger-scale devices.

One early approach was to make electrodes first, and then scatter devices randomly on a surface, with the expectation that at least a few would land where desired, a method Rothemund describes as “spray and pray.”

In 2009, Rothemund and colleagues at IBM Research first described a technique through which DNA origami can be positioned at precise locations on surfaces using electron-beam lithography to etch sticky binding sites that have the same shape as the origami. For example, triangular sticky patches bind triangularly folded DNA.

Over the last seven years, Rothemund and Ashwin Gopinath, senior postdoctoral scholar in bioengineering at Caltech, have refined and extended this technique so that DNA shapes can be precisely positioned on almost any surface used in the manufacture of computer chips. In the Nature paper, they report the first application of the technique—using DNA origami to install fluorescent molecules into microscopic light sources.

“It’s like using DNA origami to screw molecular light bulbs into microscopic lamps,” Rothemund says.

In this case, the lamps are microfabricated structures called photonic crystal cavities (PCCs), which are tuned to resonate at a particular wavelength of light, much like a tuning fork vibrates with a particular pitch. Created within a thin glass-like membrane, a PCC takes the form of a bacterium-shaped defect within an otherwise perfect honeycomb of holes.

“Depending on the exact size and spacing of the holes, a particular wavelength of light reflects off the edge of the cavity and gets trapped inside,” says Gopinath, the lead author of the study. He built PCCs that are tuned to resonate at around 660 nanometers, the wavelength corresponding to a deep shade of the color red. Fluorescent molecules tuned to glow at a similar wavelength light up the lamps—provided they stick to exactly the right place within the PCC.

“A fluorescent molecule tuned to the same color as a PCC actually glows more brightly inside the cavity, but the strength of this coupling effect depends strongly on the molecule’s position within the cavity. A few tens of nanometers is the difference between the molecule glowing brightly, or not at all,” Gopinath says.

By moving DNA origami through the PCCs in 20-nanometer steps, the researchers found that they could map out a checkerboard pattern of hot and cold spots, where the molecular light bulbs either glowed weakly or strongly. As a result, they were able to use DNA origami to position fluorescent molecules to make lamps of varying intensity. Similar structures have been proposed to power quantum computers and for use in other optical applications that require many tiny light sources integrated together on a single chip.

“All previous work coupling light emitters to PCCs only successfully created a handful of working lamps, owing to the extraordinary difficulty of reproducibly controlling the number and position of emitters in a cavity,” Gopinath says. To prove their new technology, the researchers decided to scale-up and provide a visually compelling demonstration. By creating PCCs with different numbers of binding sites, Gopinath was able to reliably install any number from zero to seven DNA origami, allowing him to digitally control the brightness of each lamp. He treated each lamp as a pixel with one of eight different intensities, and produced an array of 65,536 of the PCC pixels (a 256 x 256 pixel grid) to create a reproduction of Van Gogh’s “The Starry Night.”

Now that the team can reliably combine molecules with PCCs, they are working to improve the light emitters. Currently, the fluorescent molecules last about 45 seconds before reacting with oxygen and “burning out,” and they emit a few shades of red rather than a single pure color. Solving both these problems will help with applications such as quantum computers.

“Aside from applications, there’s a lot of fundamental science to be done,” Gopinath says.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Engineering and mapping nanocavity emission via precision placement of DNA origami by Ashwin Gopinath, Evan Miyazono, Andrei Faraon, & Paul W. K. Rothemund. Nature (2016) doi:10.1038/nature18287 Published online 11 July 2016

This paper is behind a paywall.