For the same reason some people like ‘Christmas in July’ events, I like to occasionally feature a nonseasonal story. Especially since the area where I live is going through an unseasonal cold snap and will be followed shortly by anomalously hot temperatures. So, more or less fittingly, an April 10, 2023 news item announces a new fabric,

Three engineers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst have invented a fabric that concludes the 80-year quest to make a synthetic textile modeled on Polar bear fur. The results, published recently in the journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, are already being developed into commercially available products. [ACS is American Chemical Society.]

…

Nice to see a properly drawn polar bear. Back to the research, an April 10, 2023 University of Massachusetts Amherst news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides a brief history of the research and a few technical details about the current work, Note: Links have been removed,

Polar bears live in some of the harshest conditions on earth, shrugging off Arctic temperatures as low as -50 Fahrenheit. While the bears have many adaptations that allow them to thrive when the temperature plummets, since the 1940s scientists have focused on one in particular: their fur. How, the scientific community has asked, does a polar bear’s fur keep them warm?

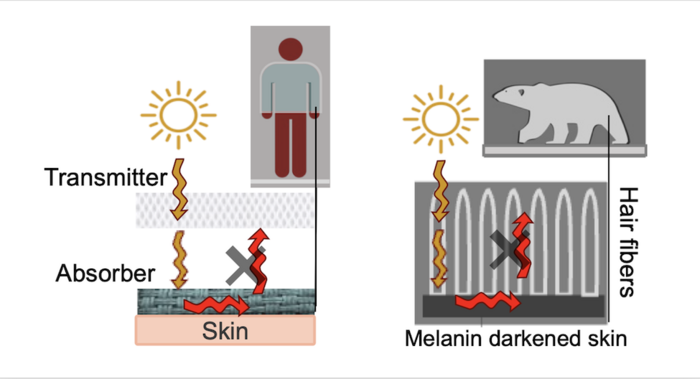

Typically, we think that the way to stay warm is to insulate ourselves from the weather. But there’s another way: One of the major discoveries of the last few decades is that many polar animals actively use the sunlight to maintain their temperature, and polar bear fur is a well-known case in point.

Scientists have known for decades that part of the bears’ secret is their white fur. One might think that black fur would be better at absorbing heat, but it turns out that the polar bears’ fur is extremely effective at transmitting solar radiation toward the bears’ skin.

“But the fur is only half the equation,” says the paper’s senior author, Trisha L. Andrew, associate professor of chemistry and adjunct in chemical engineering at UMass Amherst. “The other half is the polar bears’ black skin.”

As Andrew explains it, polar bear fur is essentially a natural fiberoptic, conducting sunlight down to the bears’ skin, which absorbs the light, heating the bear. But the fur is also exceptionally good at preventing the now-warmed skin from radiating out all that hard-won warmth. When the sun shines, it’s like having a thick blanket that warms itself up, and then traps that warmth next to your skin.

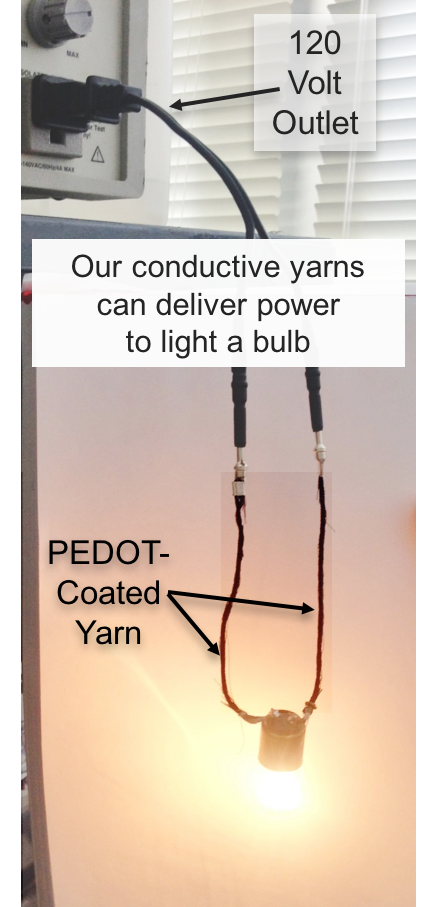

What Andrew and her team have done is to engineer a bilayer fabric whose top layer is composed of threads that, like polar bear fur, conduct visible light down to the lower layer, which is made of nylon and coated with a dark material called PEDOT [Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)]. PEDOT, like the polar bears’ skin, warms efficiently.

So efficiently, in fact, that a jacket made of such material is 30% lighter than the same jacket made of cotton yet will keep you comfortable at temperatures 10 degrees Celsius colder than the cotton jacket could handle, as long as the sun is shining or a room is well lit.

“Space heating consumes huge amounts of energy that is mostly fossil fuel-derived,” says Wesley Viola, the paper’s lead author, who completed his Ph.D. in chemical engineering at UMass and is now at Andrew’s startup, Soliyarn, LLC. “While our textile really shines as outerwear on sunny days, the light-heat trapping structure works efficiently enough to imagine using existing indoor lighting to directly heat the body. By focusing energy resources on the ‘personal climate’ around the body, this approach could be far more sustainable than the status quo.”

The research, which was supported by the National Science Foundation, is already being applied, and Soliyarn has begun production of the PEDOT-coated cloth.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Solar Thermal Textiles for On-Body Radiative Energy Collection Inspired by Polar Animals by Wesley Viola, Peiyao Zhao, and Trisha L. Andrew. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 15, 19393–19402 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.2c23075 Publication Date: April 5, 2023 Copyright © 2023 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.

You can find Soliyarn here.