Within one day of each other in October 2018, two different teams working on memristors with applications to neuroprosthetics and neuromorphic computing (brainlike computing) announced their results.

Russian team

An October 15, 2018 (?) Lobachevsky University press release (also published on October 15, 2018 on EurekAlert) describes a new approach to memristors,

Biological neurons are coupled unidirectionally through a special junction called a synapse. An electrical signal is transmitted along a neuron after some biochemical reactions initiate a chemical release to activate an adjacent neuron. These junctions are crucial for cognitive functions, such as perception, learning and memory.

A group of researchers from Lobachevsky University in Nizhny Novgorod investigates the dynamics of an individual memristive device when it receives a neuron-like signal as well as the dynamics of a network of analog electronic neurons connected by means of a memristive device. According to Svetlana Gerasimova, junior researcher at the Physics and Technology Research Institute and at the Neurotechnology Department of Lobachevsky University, this system simulates the interaction between synaptically coupled brain neurons while the memristive device imitates a neuron axon.

A memristive device is a physical model of Chua’s [Dr. Leon Chua, University of California at Berkeley; see my May 9, 2008 posting for a brief description Dr. Chua’s theory] memristor, which is an electric circuit element capable of changing its resistance depending on the electric signal received at the input. The device based on a Au/ZrO2(Y)/TiN/Ti structure demonstrates reproducible bipolar switching between the low and high resistance states. Resistive switching is determined by the oxidation and reduction of segments of conducting channels (filaments) in the oxide film when voltage with different polarity is applied to it. In the context of the present work, the ability of a memristive device to change conductivity under the action of pulsed signals makes it an almost ideal electronic analog of a synapse.

Lobachevsky University scientists and engineers supported by the Russian Science Foundation (project No.16-19-00144) have experimentally implemented and theoretically described the synaptic connection of neuron-like generators using the memristive interface and investigated the characteristics of this connection.

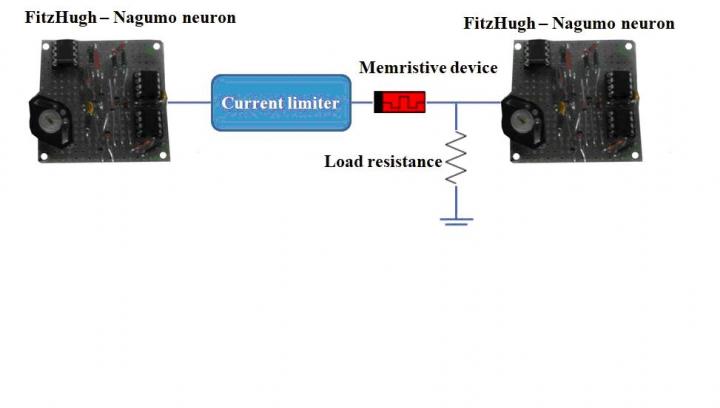

“Each neuron is implemented in the form of a pulse signal generator based on the FitzHugh-Nagumo model. This model provides a qualitative description of the main neurons’ characteristics: the presence of the excitation threshold, the presence of excitable and self-oscillatory regimes with the possibility of a changeover. At the initial time moment, the master generator is in the self-oscillatory mode, the slave generator is in the excitable mode, and the memristive device is used as a synapse. The signal from the master generator is conveyed to the input of the memristive device, the signal from the output of the memristive device is transmitted to the input of the slave generator via the loading resistance. When the memristive device switches from a high resistance to a low resistance state, the connection between the two neuron-like generators is established. The master generator goes into the oscillatory mode and the signals of the generators are synchronized. Different signal modulation mode synchronizations were demonstrated for the Au/ZrO2(Y)/TiN/Ti memristive device,” – says Svetlana Gerasimova.

UNN researchers believe that the next important stage in the development of neuromorphic systems based on memristive devices is to apply such systems in neuroprosthetics. Memristive systems will provide a highly efficient imitation of synaptic connection due to the stochastic nature of the memristive phenomenon and can be used to increase the flexibility of the connections for neuroprosthetic purposes. Lobachevsky University scientists have vast experience in the development of neurohybrid systems. In particular, a series of experiments was performed with the aim of connecting the FitzHugh-Nagumo oscillator with a biological object, a rat brain hippocampal slice. The signal from the electronic neuron generator was transmitted through the optic fiber communication channel to the bipolar electrode which stimulated Schaffer collaterals (axons of pyramidal neurons in the CA3 field) in the hippocampal slices. “We are going to combine our efforts in the design of artificial neuromorphic systems and our experience of working with living cells to improve flexibility of prosthetics,” concludes S. Gerasimova.

The results of this research were presented at the 38th International Conference on Nonlinear Dynamics (Dynamics Days Europe) at Loughborough University (Great Britain).

This diagram illustrates an aspect of the work,

Caption: Schematic of electronic neurons coupling via a memristive device. Credit: Lobachevsky University

US team

The American Institute of Physics (AIP) announced the publication of a ‘memristor paper’ by a team from the University of Southern California (USC) in an October 16, 2018 news item on phys.org,

Just like their biological counterparts, hardware that mimics the neural circuitry of the brain requires building blocks that can adjust how they synapse, with some connections strengthening at the expense of others. One such approach, called memristors, uses current resistance to store this information. New work looks to overcome reliability issues in these devices by scaling memristors to the atomic level.

An October 16, 2018 AIP news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, delves further into the particulars of this particular piece of memristor research,

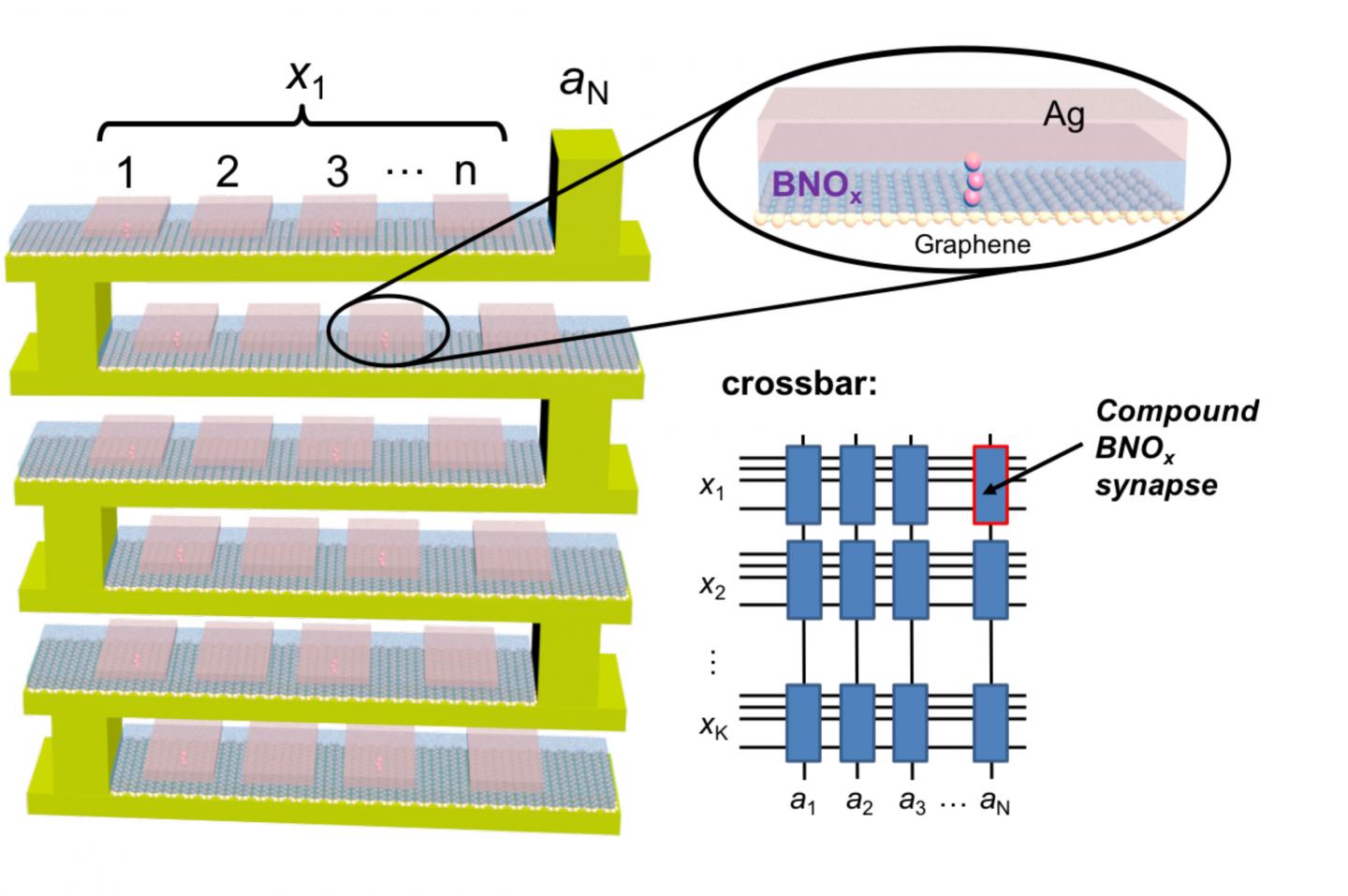

A group of researchers demonstrated a new type of compound synapse that can achieve synaptic weight programming and conduct vector-matrix multiplication with significant advances over the current state of the art. Publishing its work in the Journal of Applied Physics, from AIP Publishing, the group’s compound synapse is constructed with atomically thin boron nitride memristors running in parallel to ensure efficiency and accuracy.

The article appears in a special topic section of the journal devoted to “New Physics and Materials for Neuromorphic Computation,” which highlights new developments in physical and materials science research that hold promise for developing the very large-scale, integrated “neuromorphic” systems of tomorrow that will carry computation beyond the limitations of current semiconductors today.

“There’s a lot of interest in using new types of materials for memristors,” said Ivan Sanchez Esqueda, an author on the paper. “What we’re showing is that filamentary devices can work well for neuromorphic computing applications, when constructed in new clever ways.”

Current memristor technology suffers from a wide variation in how signals are stored and read across devices, both for different types of memristors as well as different runs of the same memristor. To overcome this, the researchers ran several memristors in parallel. The combined output can achieve accuracies up to five times those of conventional devices, an advantage that compounds as devices become more complex.

The choice to go to the subnanometer level, Sanchez said, was born out of an interest to keep all of these parallel memristors energy-efficient. An array of the group’s memristors were found to be 10,000 times more energy-efficient than memristors currently available.

“It turns out if you start to increase the number of devices in parallel, you can see large benefits in accuracy while still conserving power,” Sanchez said. Sanchez said the team next looks to further showcase the potential of the compound synapses by demonstrating their use completing increasingly complex tasks, such as image and pattern recognition.

Here’s an image illustrating the parallel artificial synapses,

Caption: Hardware that mimics the neural circuitry of the brain requires building blocks that can adjust how they synapse. One such approach, called memristors, uses current resistance to store this information. New work looks to overcome reliability issues in these devices by scaling memristors to the atomic level. Researchers demonstrated a new type of compound synapse that can achieve synaptic weight programming and conduct vector-matrix multiplication with significant advances over the current state of the art. They discuss their work in this week’s Journal of Applied Physics. This image shows a conceptual schematic of the 3D implementation of compound synapses constructed with boron nitride oxide (BNOx) binary memristors, and the crossbar array with compound BNOx synapses for neuromorphic computing applications. Credit: Ivan Sanchez Esqueda

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Efficient learning and crossbar operations with atomically-thin 2-D material compound synapses by Ivan Sanchez Esqueda, Huan Zhao and Han Wang. The article will appear in the Journal of Applied Physics Oct. 16, 2018 (DOI: 10.1063/1.5042468).

This paper is behind a paywall.

*Title corrected from ‘Two approaches to memristors featuring’ to ‘Two approaches to memristors’ on May 31, 2019 at 1455 hours PDT.