A May 7, 2020 Purdue University news release (also on EurekAlert) describes a new approach for energy-efficient hardware in support of artificial intelligence (AI) systems,

To just solve a puzzle or play a game, artificial intelligence can require software running on thousands of computers. That could be the energy that three nuclear plants produce in one hour.

A team of engineers has created hardware that can learn skills using a type of AI that currently runs on software platforms. Sharing intelligence features between hardware and software would offset the energy needed for using AI in more advanced applications such as self-driving cars or discovering drugs.

“Software is taking on most of the challenges in AI. If you could incorporate intelligence into the circuit components in addition to what is happening in software, you could do things that simply cannot be done today,” said Shriram Ramanathan, a professor of materials engineering at Purdue University.

AI hardware development is still in early research stages. Researchers have demonstrated AI in pieces of potential hardware, but haven’t yet addressed AI’s large energy demand.

As AI penetrates more of daily life, a heavy reliance on software with massive energy needs is not sustainable, Ramanathan said. If hardware and software could share intelligence features, an area of silicon might be able to achieve more with a given input of energy.

Ramanathan’s team is the first to demonstrate artificial “tree-like” memory in a piece of potential hardware at room temperature. Researchers in the past have only been able to observe this kind of memory in hardware at temperatures that are too low for electronic devices.

The results of this study are published in the journal Nature Communications.

The hardware that Ramanathan’s team developed is made of a so-called quantum material. These materials are known for having properties that cannot be explained by classical physics. Ramanathan’s lab has been working to better understand these materials and how they might be used to solve problems in electronics.

Software uses tree-like memory to organize information into various “branches,” making that information easier to retrieve when learning new skills or tasks.

The strategy is inspired by how the human brain categorizes information and makes decisions.

“Humans memorize things in a tree structure of categories. We memorize ‘apple’ under the category of ‘fruit’ and ‘elephant’ under the category of ‘animal,’ for example,” said Hai-Tian Zhang, a Lillian Gilbreth postdoctoral fellow in Purdue’s College of Engineering. “Mimicking these features in hardware is potentially interesting for brain-inspired computing.”

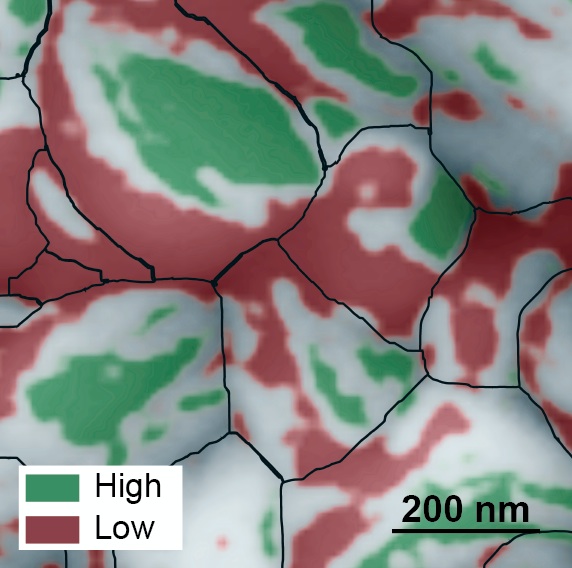

The team introduced a proton to a quantum material called neodymium nickel oxide. They discovered that applying an electric pulse to the material moves around the proton. Each new position of the proton creates a different resistance state, which creates an information storage site called a memory state. Multiple electric pulses create a branch made up of memory states.

“We can build up many thousands of memory states in the material by taking advantage of quantum mechanical effects. The material stays the same. We are simply shuffling around protons,” Ramanathan said.

Through simulations of the properties discovered in this material, the team showed that the material is capable of learning the numbers 0 through 9. The ability to learn numbers is a baseline test of artificial intelligence.

The demonstration of these trees at room temperature in a material is a step toward showing that hardware could offload tasks from software.

“This discovery opens up new frontiers for AI that have been largely ignored because implementing this kind of intelligence into electronic hardware didn’t exist,” Ramanathan said.

The material might also help create a way for humans to more naturally communicate with AI.

“Protons also are natural information transporters in human beings. A device enabled by proton transport may be a key component for eventually achieving direct communication with organisms, such as through a brain implant,” Zhang said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the published study,

Perovskite neural trees by Hai-Tian Zhang, Tae Joon Park, Shriram Ramanathan. Nature Communications volume 11, Article number: 2245 (2020) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-16105-y Published: 07 May 2020

This paper is open access.

![[downloaded from http://www.wiley-vch.de/vch/journals/2002/press/201429press.pdf]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/PerovskiteSolarCell.gif)