What a gorgeous image!

The compound eye of a fly inspired Stanford researchers to create a compound solar cell consisting of perovskite microcells encapsulated in a hexagon-shaped scaffold. (Image credit: Thomas Shahan/Creative Commons)

An August 31, 2017 news item on Nanowerk describes research into solar cells being performed at Stanford University (Note: A link has been removed),

Packing tiny solar cells together, like micro-lenses in the compound eye of an insect, could pave the way to a new generation of advanced photovoltaics, say Stanford University scientists.

In a new study, the Stanford team used the insect-inspired design to protect a fragile photovoltaic material called perovskite from deteriorating when exposed to heat, moisture or mechanical stress. The results are published in the journal Energy & Environmental Science (“Scaffold-reinforced perovskite compound solar cells”).

An August 31, 2017 Stanford University news release (also on EurekAlert) by Mark Schwartz, which originated the news item,

“Perovskites are promising, low-cost materials that convert sunlight to electricity as efficiently as conventional solar cells made of silicon,” said Reinhold Dauskardt, a professor of materials science and engineering and senior author of the study. “The problem is that perovskites are extremely unstable and mechanically fragile. They would barely survive the manufacturing process, let alone be durable long term in the environment.”

Most solar devices, like rooftop panels, use a flat, or planar, design. But that approach doesn’t work well with perovskite solar cells.

“Perovskites are the most fragile materials ever tested in the history of our lab,” said graduate student Nicholas Rolston, a co-lead author of the E&ES study. “This fragility is related to the brittle, salt-like crystal structure of perovskite, which has mechanical properties similar to table salt.”

Eye of the fly

To address the durability challenge, the Stanford team turned to nature.

“We were inspired by the compound eye of the fly, which consists of hundreds of tiny segmented eyes,” Dauskardt explained. “It has a beautiful honeycomb shape with built-in redundancy: If you lose one segment, hundreds of others will operate. Each segment is very fragile, but it’s shielded by a scaffold wall around it.”

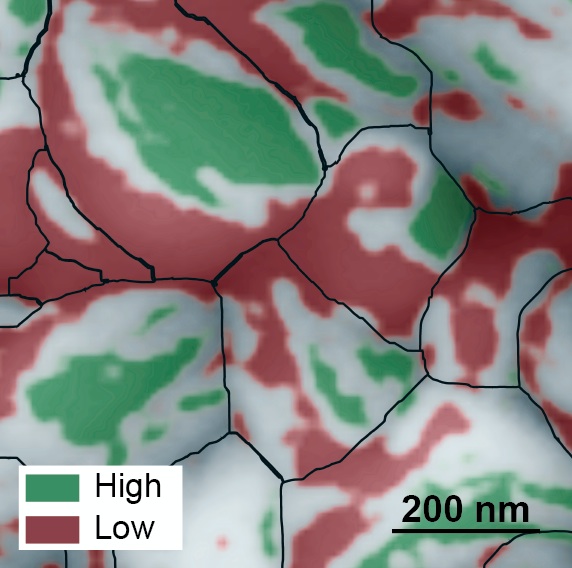

Scaffolds in a compound solar cell filled with perovskite after fracture testing. (Image credit: Dauskardt Lab/Stanford University)

Using the compound eye as a model, the researchers created a compound solar cell consisting of a vast honeycomb of perovskite microcells, each encapsulated in a hexagon-shaped scaffold just 0.02 inches (500 microns) wide.

“The scaffold is made of an inexpensive epoxy resin widely used in the microelectronics industry,” Rolston said. “It’s resilient to mechanical stresses and thus far more resistant to fracture.”

Tests conducted during the study revealed that the scaffolding had little effect on how efficiently perovskite converted light into electricity.

“We got nearly the same power-conversion efficiencies out of each little perovskite cell that we would get from a planar solar cell,” Dauskardt said. “So we achieved a huge increase in fracture resistance with no penalty for efficiency.”

Durability

But could the new device withstand the kind of heat and humidity that conventional rooftop solar panels endure?

To find out, the researchers exposed encapsulated perovskite cells to temperatures of 185 F (85 C) and 85 percent relative humidity for six weeks. Despite these extreme conditions, the cells continued to generate electricity at relatively high rates of efficiency.

Dauskardt and his colleagues have filed a provisional patent for the new technology. To improve efficiency, they are studying new ways to scatter light from the scaffold into the perovskite core of each cell.

“We are very excited about these results,” he said. “It’s a new way of thinking about designing solar cells. These scaffold cells also look really cool, so there are some interesting aesthetic possibilities for real-world applications.”

Researchers have also made this image available,

Caption: A compound solar cell illuminated from a light source below. Hexagonal scaffolds are visible in the regions coated by a silver electrode. The new solar cell design could help scientists overcome a major roadblock to the development of perovskite photovoltaics. Credit: Dauskardt Lab/Stanford University

Not quite as weirdly beautiful as the insect eyes.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Scaffold-reinforced perovskite compound solar cells by Brian L. Watson, Nicholas Rolston, Adam D. Printz, and Reinhold H. Dauskardt. Energy & Environmental Science 2017 DOI: 10.1039/C7EE02185B first published on 23 Aug 2017

This paper is behind a paywall.