A Jan. 13, 2016 Rice University news release (also on EurekAlert) highlights computational research on hybrid material (graphene-boron nitride),

Developing novel materials from the atoms up goes faster when some of the trial and error is eliminated. A new Rice University and Montreal Polytechnic study aims to do that for graphene and boron nitride hybrids.

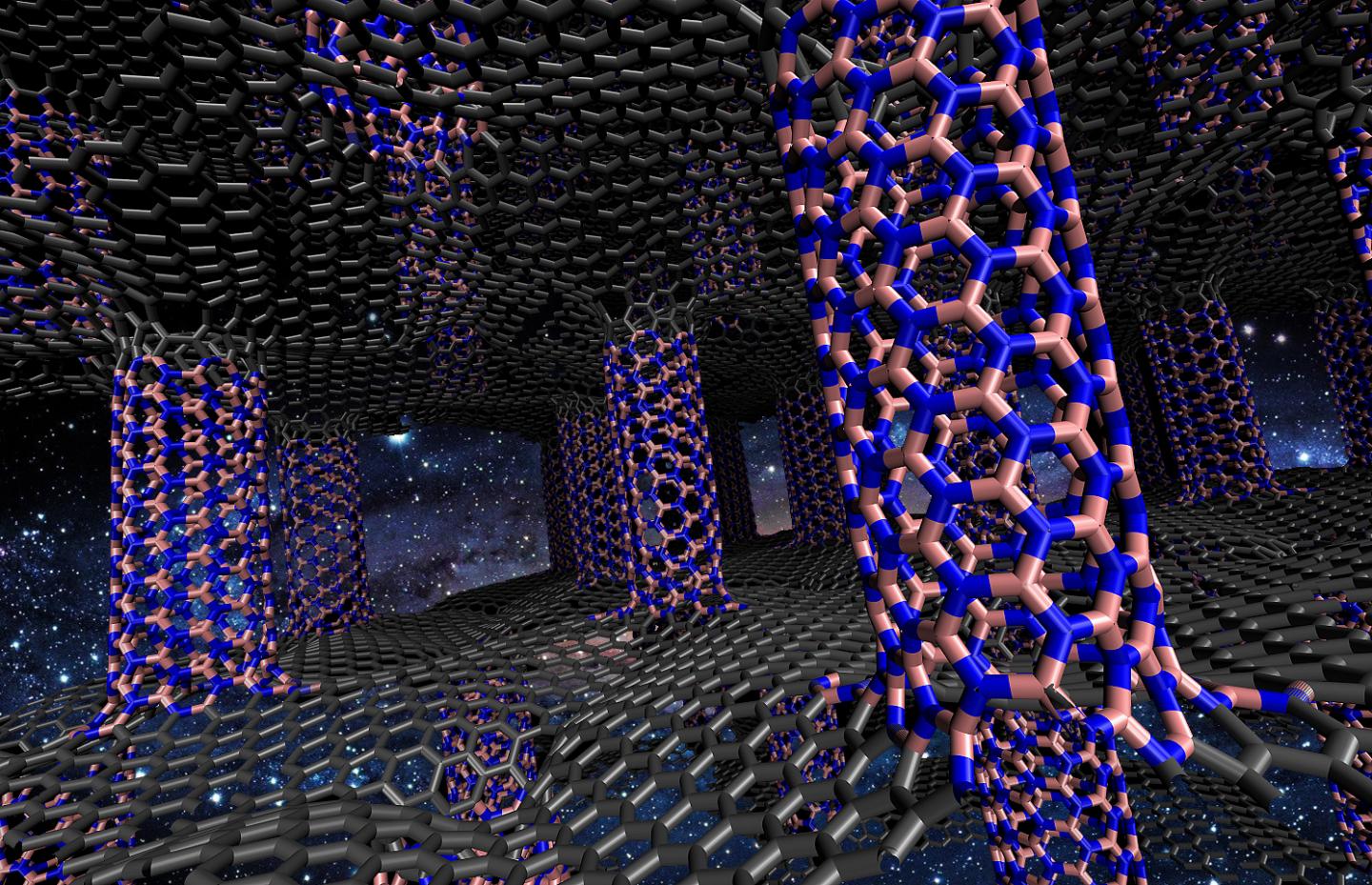

Rice materials scientist Rouzbeh Shahsavari and Farzaneh Shayeganfar, a postdoctoral researcher at Montreal Polytechnic (also known as École Polytechnique de Montréal or Polytechnique de Montréal), designed computer simulations that combine graphene, the atom-thick form of carbon, with either carbon or boron nitride nanotubes.

Their hope is that such hybrids can leverage the best aspects of their constituent materials. Defining the properties of various combinations would simplify development for manufacturers who want to use these exotic materials in next-generation electronics. The researchers found not only electronic but also magnetic properties that could be useful.

…

Shahsavari’s lab studies materials to see how they can be made more efficient, functional and environmentally friendly. They include macroscale materials like cement and ceramics as well as nanoscale hybrids with unique properties.

“Whether it’s on the macro- or microscale, if we can know specifically what a hybrid will do before anyone goes to the trouble of fabricating it, we can save cost and time and perhaps enable new properties not possible with any of the constituents,” Shahsavari said.

His lab’s computer models simulate how the intrinsic energies of atoms influence each other as they bond into molecules. For the new work, the researchers modeled hybrid structures of graphene and carbon nanotubes and of graphene and boron nitride nanotubes.

“We wanted to investigate and compare the electronic and potentially magnetic properties of different junction configurations, including their stability, electronic band gaps and charge transfer,” he said. “Then we designed three different nanostructures with different junction geometry.”

Two were hybrids with graphene layers seamlessly joined to carbon nanotubes. The other was similar but, for the first time, they modeled a hybrid with boron nitride nanotubes. How the sheets and tubes merged determined the hybrid’s properties. They also built versions with nanotubes sandwiched between graphene layers.

Graphene is a perfect conductor when its atoms align as hexagonal rings, but the material becomes strained when it deforms to accommodate nanotubes in hybrids. The atoms balance their energies at these junctions by forming five-, seven- or eight-member rings. These all induce changes in the way electricity flows across the junctions, turning the hybrid material into a valuable semiconductor.

The researchers’ calculations allowed them to map out a number of effects. For example, it turned out the junctions of the hybrid system create pseudomagnetic fields.

“The pseudomagnetic field due to strain was reported earlier for graphene, but not these hybrid boron nitride and carbon nanostructures where strain is inherent to the system,” Shahsavari said. He noted the effect may be useful in spintronic and nano-transistor applications.

“The pseudomagnetic field causes charge carriers in the hybrid to circulate as if under the influence of an applied external magnetic field,” he said. “Thus, in view of the exceptional flexibility, strength and thermal conductivity of hybrid carbon and boron nitride systems, we propose the pseudomagnetic field may be a viable way to control the electronic structure of new materials.”

All the effects serve as a road map for nanoengineering applications, Shahsavari said.

“We’re laying the foundations for a range of tunable hybrid architectures, especially for boron nitride, which is as promising as graphene but much less explored,” he said. “Scientists have been studying all-carbon structures for years, but the development of boron nitride and other two-dimensional materials and their various combinations with each other gives us a rich set of possibilities for the design of materials with never-seen-before properties.”

Shahsavari is an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering and of materials science and nanoengineering.

###

Rice supported the research, and computational resources were provided by Calcul Quebec and Compute Canada.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Electronic and pseudomagnetic properties of hybrid carbon/boron-nitride nanomaterials via ab-initio calculations and elasticity theory by Farzaneh Shayeganfar and Rouzbeh Shahsavari. Carbon Volume 99, April 2016, Pages 523–532 doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2015.12.050

This paper is behind a paywall.

Here’s an image illustrating the hybrid material,