This is to use an old term, ‘mindblowing’. Apparently, there are two types of the liquid we call water according to a Nov. 10, 2016 news item on phys.org,

There are two types of liquid water, according to research carried out by an international scientific collaboration. This new peculiarity adds to the growing list of strange phenomena in what we imagine is a simple substance. The discovery could have implications for making and using nanoparticles as well as in understanding how proteins fold into their working shape in the body or misfold to cause diseases such as Alzheimer’s or CJD [Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease].

A Nov. 10, 2016 Inderscience Publishers news release, which originated the news item, expands on the theme,

Writing in the International Journal of Nanotechnology, Oxford University’s Laura Maestro and her colleagues in Italy, Mexico, Spain and the USA, explain how the physical and chemical properties of water have been studied for more than a century and revealed some odd behavior not seen in other substances. For instance, when water freezes it expands. By contrast, almost every other known substance contracts when it is cooled. Water also exists as solid, liquid and gas within a very small temperature range (100 degrees Celsius) whereas the melting and boiling points of most other compounds span a much greater range.

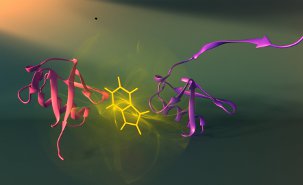

Many of water’s bizarre properties are due to the molecule’s ability to form short-lived connections with each other known as hydrogen bonds. There is a residual positive charge on the hydrogen atoms in the V-shaped water molecule either or both of which can form such bonds with the negative electrons on the oxygen atom at the point of the V. This makes fleeting networks in water possible that are frozen in place when the liquid solidifies. They bonds are so short-lived that they do not endow the liquid with any structure or memory, of course.

The team has looked closely at several physical properties of water like its dielectric constant (how well an electric field can permeate a substance) or the proton-spin lattice relaxation (the process by which the magnetic moments of the hydrogen atoms in water can lose energy having been excited to a higher level). They have found that these phenomena seem to flip between two particular characters at around 50 degrees Celsius, give or take 10 degrees, i.e. from 40 to 60 degrees Celsius. The effect is that thermal expansion, speed of sound and other phenomena switch between two different states at this crossover temperature.

These two states could have important implications for studying and using nanoparticles where the character of water at the molecule level becomes important for the thermal and optical properties of such particles. Gold and silver nanoparticles are used in nanomedicine for diagnostics and as antibacterial agents, for instance. Moreover, the preliminary findings suggest that the structure of liquid water can strongly influence the stability of proteins and how they are denatured at the crossover temperature, which may well have implications for understanding protein processing in the food industry but also in understanding how disease arises when proteins misfold.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

On the existence of two states in liquid water: impact on biological and nanoscopic systems

by L.M. Maestro, M.I. Marqués, E. Camarillo, D. Jaque, J. García Solé, J.A. Gonzalo, F. Jaque, Juan C. Del Valle, F. Mallamace, H.E. Stanley.

International Journal of Nanotechnology (IJNT), Vol. 13, No. 8/9, 2016 DOI: 10.1504/IJNT.2016.079670

This paper is behind a paywall.