it seems IBM is very excited about neuromorphic computing. First, there’s an August 10, 2023 news article by Shiona McCallum & Chris Vallance for British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) online news,

Concerns have been raised about emissions associated with warehouses full of computers powering AI systems.

IBM said its prototype could lead to more efficient, less battery draining AI chips for smartphones.

Its efficiency is down to components that work in a similar way to connections in human brains, it said.

Compared to traditional computers, “the human brain is able to achieve remarkable performance while consuming little power”, said scientist Thanos Vasilopoulos, based at IBM’s research lab in Zurich, Switzerland.

…

I sense a memristor about to be mentioned, from McCallum & Vallance’s article August 10, 2023 news article,

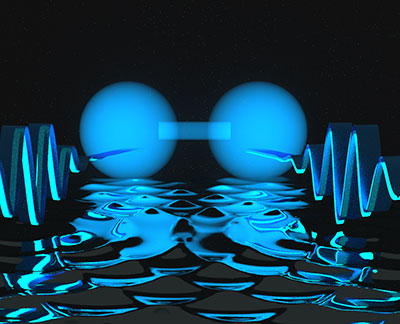

Most chips are digital, meaning they store information as 0s and 1s, but the new chip uses components called memristors [memory resistors] that are analogue and can store a range of numbers.

You can think of the difference between digital and analogue as like the difference between a light switch and a dimmer switch.

The human brain is analogue, and the way memristors work is similar to the way synapses in the brain work.

Prof Ferrante Neri, from the University of Surrey, explains that memristors fall into the realm of what you might call nature-inspired computing that mimics brain function.

A memristor could “remember” its electric history, in a similar way to a synapse in a biological system.

“Interconnected memristors can form a network resembling a biological brain,” he said.

He was cautiously optimistic about the future for chips using this technology: “These advancements suggest that we may be on the cusp of witnessing the emergence of brain-like chips in the near future.”

However, he warned that developing a memristor-based computer is not a simple task and that there would be a number of challenges ahead for widespread adoption, including the costs of materials and manufacturing difficulties.

…

Neri is most likely aware that researchers have been excited that ‘green’ computing could be made possible by memristors since at least 2008 (see my May 9, 2008 posting “Memristors and green energy“).

As it turns out, IBM published two studies on neuromorphic chips in August 2023.

The first study (mentioned in the BBC article) is also described in an August 22, 2023 article by Peter Grad for Tech Xpore. This one is a little more technical than the BBC article,

For those who are truly technical, here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

A 64-core mixed-signal in-memory compute chip based on phase-change memory for deep neural network inference by Manuel Le Gallo, Riduan Khaddam-Aljameh, Milos Stanisavljevic, Athanasios Vasilopoulos, Benedikt Kersting, Martino Dazzi, Geethan Karunaratne, Matthias Brändli, Abhairaj Singh, Silvia M. Müller, Julian Büchel, Xavier Timoneda, Vinay Joshi, Malte J. Rasch, Urs Egger, Angelo Garofalo, Anastasios Petropoulos, Theodore Antonakopoulos, Kevin Brew, Samuel Choi, Injo Ok, Timothy Philip, Victor Chan, Claire Silvestre, Ishtiaq Ahsan, Nicole Saulnier, Nicole Saulnier, Pier Andrea Francese, Evangelos Eleftheriou & Abu Sebastian. Nature Electronics (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41928-023-01010-1 Published: 10 August 2023

This paper is behind a paywall.

Before getting to the second paper, there’s an August 23, 2023 IBM blog post by Mike Murphy announcing its publication in Nature, Note: Links have been removed,

Although we’re still just at the precipice of the AI revolution, artificial intelligence has already begun to revolutionize the way we live and work. There’s just one problem: AI technology is incredibly power-hungry. By some estimates, running a large AI model generates more emissions over its lifetime than the average American car.

The future of AI requires new innovations in energy efficiency, from the way models are designed down to the hardware that runs them. And in a world that’s increasingly threatened by climate change, any advances in AI energy efficiency are essential to keep pace with AI’s rapidly expanding carbon footprint.

And one of the latest breakthroughs in AI efficiency from IBM Research relies on analog chips — ones that consume much less power. In a paper published in Nature today,1 researchers from IBM labs around the world presented their prototype analog AI chip for energy-efficient speech recognition and transcription. Their design was utilized in two AI inference experiments, and in both cases, the analog chips performed these tasks just as reliably as comparable all-digital devices — but finished the tasks faster and used less energy.

The concept of designing analog chips for AI inference is not new — researchers have been contemplating the idea for years. Back in 2021, a team at IBM developed chips that use Phase-change memory (PCM) works when an electrical pulse is applied to a material, which changes the conductance of the device. The material switches between amorphous and crystalline phases, where a lower electrical pulse will make the device more crystalline, providing less resistance, and a high enough electrical pulse makes the device amorphous, resulting in large resistance. Instead of recording the usual 0s or 1s you would see in digital systems, the PCM device records its state as a continuum of values between the amorphous and crystalline states. This value is called a synaptic weight, which can be stored in the physical atomic configuration of each PCM device. The memory is non-volatile, so the weights are retained when the power supply is switched off.phase-change memory to encode the weights of a neural network directly onto the physical chip. But previous research in the field hasn’t shown how chips like these could be used on the massive models we see dominating the AI landscape today. For example, GPT-3, one of the larger popular models, has 175 billion parameters, or weights.

Murphy also explains the difference (for amateurs like me) between this work and the earlier published study, from the August 23, 2023 IBM blog post, Note: Links have been removed,

Natural-language tasks aren’t the only AI problems that analog AI could solve — IBM researchers are working on a host of other uses. In a paper published earlier this month in Nature Electronics, the team showed it was possible to use an energy-efficient analog chip design for scalable mixed-signal architecture that can achieve high accuracy in the CIFAR-10 image dataset for computer vision image recognition.

These chips were conceived and designed by IBM researchers in the Tokyo, Zurich, Yorktown Heights, New York, and Almaden, California labs, and built by an external fabrication company. The phase change memory and metal levels were processed and validated at IBM Research’s lab in the Albany Nanotech Complex.

If you were to combine the benefits of the work published today in Nature, such as large arrays and parallel data-transport, with the capable digital compute-blocks of the chip shown in the Nature Electronics paper, you would see many of the building blocks needed to realize the vision of a fast, low-power analog AI inference accelerator. And pairing these designs with hardware-resilient training algorithms, the team expects these AI devices to deliver the software equivalent of neural network accuracies for a wide range of AI models in the future.

…

Here’s a link to and a citation for the second paper,

An analog-AI chip for energy-efficient speech recognition and transcription by S. Ambrogio, P. Narayanan, A. Okazaki, A. Fasoli, C. Mackin, K. Hosokawa, A. Nomura, T. Yasuda, A. Chen, A. Friz, M. Ishii, J. Luquin, Y. Kohda, N. Saulnier, K. Brew, S. Choi, I. Ok, T. Philip, V. Chan, C. Silvestre, I. Ahsan, V. Narayanan, H. Tsai & G. W. Burr. Nature volume 620, pages 768–775 (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06337-5 Published: 23 August 2023 Issue Date: 24 August 2023

This paper is open access.