Similar to Cas9, Cas12a is has an added feature as noted in this February 15, 2018 news item on ScienceDaily,

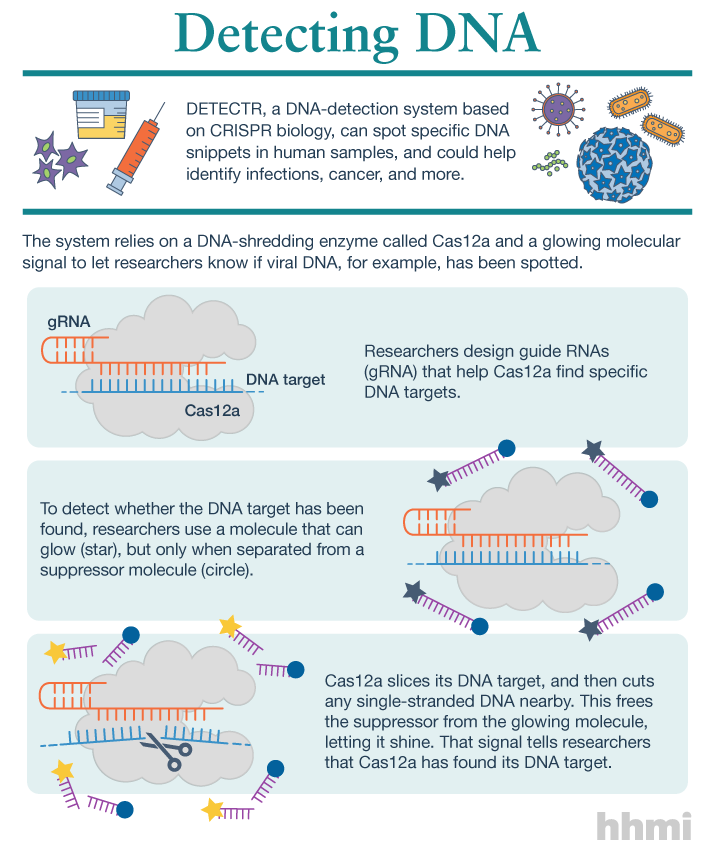

Utilizing an unsuspected activity of the CRISPR-Cas12a protein, researchers created a simple diagnostic system called DETECTR to analyze cells, blood, saliva, urine and stool to detect genetic mutations, cancer and antibiotic resistance and also diagnose bacterial and viral infections. The scientists discovered that when Cas12a binds its double-stranded DNA target, it indiscriminately chews up all single-stranded DNA. They then created reporter molecules attached to single-stranded DNA to signal when Cas12a finds its target.

A February 15, 2018 University of California at Berkeley (UC Berkeley) news release by Robert Sanders and which originated the news item, provides more detail and history,

CRISPR-Cas12a, one of the DNA-cutting proteins revolutionizing biology today, has an unexpected side effect that makes it an ideal enzyme for simple, rapid and accurate disease diagnostics.

Cas12a, discovered in 2015 and originally called Cpf1, is like the well-known Cas9 protein that UC Berkeley’s Jennifer Doudna and colleague Emmanuelle Charpentier turned into a powerful gene-editing tool in 2012.

CRISPR-Cas9 has supercharged biological research in a mere six years, speeding up exploration of the causes of disease and sparking many potential new therapies. Cas12a was a major addition to the gene-cutting toolbox, able to cut double-stranded DNA at places that Cas9 can’t, and, because it leaves ragged edges, perhaps easier to use when inserting a new gene at the DNA cut.

But co-first authors Janice Chen, Enbo Ma and Lucas Harrington in Doudna’s lab discovered that when Cas12a binds and cuts a targeted double-stranded DNA sequence, it unexpectedly unleashes indiscriminate cutting of all single-stranded DNA in a test tube.

Most of the DNA in a cell is in the form of a double-stranded helix, so this is not necessarily a problem for gene-editing applications. But it does allow researchers to use a single-stranded “reporter” molecule with the CRISPR-Cas12a protein, which produces an unambiguous fluorescent signal when Cas12a has found its target.

“We continue to be fascinated by the functions of bacterial CRISPR systems and how mechanistic understanding leads to opportunities for new technologies,” said Doudna, a professor of molecular and cell biology and of chemistry and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

The new DETECTR system based on CRISPR-Cas12a can analyze cells, blood, saliva, urine and stool to detect genetic mutations, cancer and antibiotic resistance as well as diagnose bacterial and viral infections. Target DNA is amplified by RPA to make it easier for Cas12a to find it and bind, unleashing indiscriminate cutting of single-stranded DNA, including DNA attached to a fluorescent marker (gold star) that tells researchers that Cas12a has found its target.

The UC Berkeley researchers, along with their colleagues at UC San Francisco, will publish their findings Feb. 15 [2018] via the journal Science’s fast-track service, First Release.

The researchers developed a diagnostic system they dubbed the DNA Endonuclease Targeted CRISPR Trans Reporter, or DETECTR, for quick and easy point-of-care detection of even small amounts of DNA in clinical samples. It involves adding all reagents in a single reaction: CRISPR-Cas12a and its RNA targeting sequence (guide RNA), fluorescent reporter molecule and an isothermal amplification system called recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA), which is similar to polymerase chain reaction (PCR). When warmed to body temperature, RPA rapidly multiplies the number of copies of the target DNA, boosting the chances Cas12a will find one of them, bind and unleash single-strand DNA cutting, resulting in a fluorescent readout.

The UC Berkeley researchers tested this strategy using patient samples containing human papilloma virus (HPV), in collaboration with Joel Palefsky’s lab at UC San Francisco. Using DETECTR, they were able to demonstrate accurate detection of the “high-risk” HPV types 16 and 18 in samples infected with many different HPV types.

“This protein works as a robust tool to detect DNA from a variety of sources,” Chen said. “We want to push the limits of the technology, which is potentially applicable in any point-of-care diagnostic situation where there is a DNA component, including cancer and infectious disease.”

The indiscriminate cutting of all single-stranded DNA, which the researchers discovered holds true for all related Cas12 molecules, but not Cas9, may have unwanted effects in genome editing applications, but more research is needed on this topic, Chen said. During the transcription of genes, for example, the cell briefly creates single strands of DNA that could accidentally be cut by Cas12a.

The activity of the Cas12 proteins is similar to that of another family of CRISPR enzymes, Cas13a, which chew up RNA after binding to a target RNA sequence. Various teams, including Doudna’s, are developing diagnostic tests using Cas13a that could, for example, detect the RNA genome of HIV.

These new tools have been repurposed from their original role in microbes where they serve as adaptive immune systems to fend off viral infections. In these bacteria, Cas proteins store records of past infections and use these “memories” to identify harmful DNA during infections. Cas12a, the protein used in this study, then cuts the invading DNA, saving the bacteria from being taken over by the virus.

The chance discovery of Cas12a’s unusual behavior highlights the importance of basic research, Chen said, since it came from a basic curiosity about the mechanism Cas12a uses to cleave double-stranded DNA.

“It’s cool that, by going after the question of the cleavage mechanism of this protein, we uncovered what we think is a very powerful technology useful in an array of applications,” Chen said.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity by Janice S. Chen, Enbo Ma, Lucas B. Harrington, Maria Da Costa, Xinran Tian, Joel M. Palefsky, Jennifer A. Doudna. Science 15 Feb 2018: eaar6245 DOI: 10.1126/science.aar6245

This paper is behind a paywall.