This time it’s the performing arts. I have one theatre and psychiatry production in Toronto and a music and medical science event in Vancouver.

Toronto’s Here are the Fragments opening on November 19, 2019

From a November 2, 2019 ArtSci Salon announcement (received via email),

An immersive theatre experience inspired by the psychiatric writing of Frantz Fanon

Here are the Fragments.

Co-produced by The ECT Collective and The Theatre Centre

November 19-December 1, 2019

Tickets: Preview $17 | Student/senior/arts worker $22 | Adult $30

Service charges may apply

Book 416-538-0988 | PURCHASE ONLINEAn immigrant psychiatrist develops psychosis and then schizophrenia. He walks a long path towards reconnection with himself, his son, and humanity.

Walk with him.

Within our immersive design (a fabric of sound, video, and live actors) lean in close to the possibilities of perceptual experience.

Schizophrenics ‘hear voices’. Schizophrenics fear loss of control over their own thoughts and bodies. But how does any one of us actually separate internal and external voices? How do we trust what we see or feel? How do we know which voices are truly our own?

Within the installation find places of retreat from chaos. Find poetry. Find critical analysis.

Explore archival material, Fanon’s writings and contemporary interviews with psychiatrists, neuroscientists, artists, and people living with schizophrenia, to reflect on the relationships between identity, history, racism and mental health.

I was able to find out more in a November 6, 2019 article at broadwayworld.com (Note: Some of this is repetitive),

How do we trust what we see or feel? How do we know which voices are truly our own? THE THEATRE CENTRE and THE ECT COLLECTIVE are proud to Co-produce HERE ARE THE FRAGMENTS., an immersive work of theatre written by Suvendrini Lena, Theatre Centre Residency artist and CAMH [ Centre for Addiction and Mental Health] Neurologist. Based on the psychiatric writing of famed political theorist Frantz Fanon and combining narratives, sensory exploration, and scientific and historical analysis, HERE ARE THE FRAGMENTS. reflects on the relationships between identity, history, racism, and mental health. FRAGMENTS. will run November 19 to December 1 at The Theatre Centre (Opening Night November 21).

HERE ARE THE FRAGMENTS. consists of live performances within an interactive installation. The plot, told in fragments, follows a psychiatrist early in his training as he develops psychosis and ultimately, treatment resistant schizophrenia. Eduard, his son, struggles to connect with his father, while the young man must also make difficult treatment decisions.

The Theatre Centre’s Franco Boni Theatre and Gallery will be transformed into an immersive interactive installation. The design will offer many spaces for exploration, investigation, and discovery, bringing audiences into the perceptual experience of Schizophrenia. The scenes unfold around you, incorporating a fabric of sound, video, and live actors. Amidst the seeming chaos there will also be areas of retreat; whispering voices, Fanon’s own books, archival materials, interviews with psychiatrists, neuroscientists, and people living with schizophrenia all merge to provoke analysis and reflection on the intersection of racism and mental health.…

Suvendrini Lena (Writer) is a playwright and neurologist. She works as the staff neurologist at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health and at the Centre for Headache at Women’s College Hospital [Toronto]. She is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology at the University of Toronto where she teaches medical students, residents, and fellows. She also teaches a course called Staging Medicine, a collaboration between The Theatre Centre and University of Toronto Postgraduate Medical Education.

…

Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), was a French West Indian psychiatrist, political philosopher, revolutionary, and writer, whose works are influential in the fields of post-colonial studies, critical theory, and Marxism. Fanon published numerous books, including Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961).

…

In addition to performances, The Theatre Centre will host a number of panels and events. Highlights include a post-show talkback with Ngozi Paul (Development Producer, Artist/Activist) and Psychiatrist Collaborator Araba Chintoh on November 22. Also of note is Our Patients and Our Selves: Experiences of Racism Among Health Care Workers with facilitator Dr. Fatimah Jackson-Best of Black Health Alliance on November 23rd and Fanon Today: A Creative Symposium on November 24th, a panel, reading, and creative discussion featuring David Austin, Frank Francis, Doris Rajan and George Elliot Clarke [formerly Toronto’s Poet Laureate and Canadian Parliamentary Poet Laureate; emphasis and link mine].

You can get more details and a link for ticket purchase here.

Sounds and Science: Vienna meets Vancouver on November 30, 2019

‘Sounds and Science’ originated at the Medical University of Vienna (Austria) as the November 6, 2019 event posting on the University of British Columbia’s (UBC) Faculty of Medicine website,

The University of British Columbia will host the first Canadian concert bringing leading musical talents of Vienna together with dramatic narratives from science and medicine.

“Sounds and Science: Vienna Meets Vancouver” is part of the President’s Concert Series, to be held Nov. 30, 2019 on UBC campus. The event is modeled on a successful concert series launched in Austria in 2014, in cooperation with the Medical University of Vienna.“Basic research tends to always stay within its own box, yet research is telling the most beautiful stories,” says Dr. Josef Penninger, director of UBC’s Life Sciences Institute, a professor of medical genetics and a Canada 150 Chair. “With this concert, we are bringing science out of the ivory tower, using the music of great composers such as Mozart, Schubert or Strauss to transport stories of discovery and insight into the major diseases that affected the composers themselves, and continue to have a significant impact on our society.”

Famous composers of the past are often seen as icons of classical music, but in fact, they were human beings, living under enormous physical constraints – perhaps more than people today, according to Dr. Manfred Hecking, an associate professor of internal medicine at the Medical University of Vienna.

“But ‘Sounds and Science’ is not primarily about suffering and disease,” says Dr. Hecking, a former member of the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra who will be playing double bass during the concert. “It is a fun way of bringing music and science together. Combining music and thought, we hope that we will reach the attendees of the ‘Sounds and Science’ concert in Vancouver on an emotional, perhaps even personal level.”

A showcase for Viennese music, played in the tradition of the Vienna Philharmonic by several of its members, as well as the world-class science being done here at UBC, “Sounds and Science” will feature talks by UBC clinical and research faculty, including Dr. Penninger. Their topics will range from healthy aging and cancer research to the historical impact of bacterial infections.

Combining music and thought, we hope that we will reach the attendees of the ‘Sounds and Science’ concert in Vancouver on an emotional, perhaps even personal level.

Dr. Manfred HeckingFaculty speaking at “Sounds and Science” will be:

Dr. Allison Eddy, professor and head, department of pediatrics, and chief, pediatric medicine, BC Children’s Hospital and BC Women’s Hospital;

Dr. Troy Grennan, clinical assistant professor, division of infectious diseases, UBC faculty of medicine;

Dr. Poul Sorensen, professor, department of pathology and laboratory medicine, UBC faculty of medicine; and

Dr. Roger Wong, executive associate dean, education and clinical professor of geriatric medicine, UBC faculty of medicine

UBC President and Vice-Chancellor Santa J. Ono and Vice President Health and Dr. Dermot Kelleher, dean, faculty of medicine and vice-president, health at UBC will also speak during the evening.The musicians include two outstanding members of the Vienna Philharmonic – violinist Prof. Günter Seifert and violist-conductor Hans Peter Ochsenhofer, who will be joined by violinist-conductor Rémy Ballot and double bassist Dr. Manfred Hecking, who serves as a regular substitute in the orchestra.

For those in whose lives intertwine music and science, the experience of cross-connection will be familiar. For Dr. Penninger, the concert represents an opportunity to bring the famous sound of the Vienna Philharmonic to UBC and British Columbia, to a new audience. “That these musicians are coming here is a fantastic recognition and acknowledgement of the amazing work being done at UBC,” he says.

“Like poetry, music is a universal language that all of us immediately understand and can relate to. Science tells the most amazing stories. Both of them bring meaning and beauty to our world.”

“Sounds and Science” – Vienna Meets Vancouver is part of the President’s Concert Series | November 30, 2019 on campus at the Old Auditorium from 6:30 to 9:30 p.m.

To learn more about the Sounds and Science concert series hosted in cooperation with the Medical University of Vienna, visit www.soundsandscience.com.

I found more information regarding logistics,

Saturday, November 30, 2019

6:30 pm

The Old Auditorium, 6344 Memorial Road, UBC

Box office and Lobby: Opens at 5:30 pm (one hour prior to start of performance)

Old Auditorium Concert Hall: Opens at 6:00 pmSounds

Günter Seifert VIOLIN

Rémy Ballot VIOLIN

Hans Peter Ochsenhofer VIOLA

Manfred Hecking DOUBLE BASSScience

Josef Penninger GENETICS

Manfred Hecking INTERNAL MEDICINE

Troy Grennan INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Poul Sorensen PATHOLOGY & LABORATORY MEDICINE

Allison Eddy PEDIATRICS

Roger Wong GERIATRICSTickets are also available in person at UBC concert box-office locations:

– Old Auditorium

– Freddie Wood Theatre

– The Chan Centre for the Performing ArtGeneral admission: $10.00

Free seating for UBC students

Purchase tickets for both President’s Concert Series events to make it a package, and save 10% on both performancesTransportation

Public and Bike Transportation

Please visit Translink for bike and transit information.

Parking

Suggested parking in the Rose Garden Parkade.

The Sounds and Science website has a feature abut the upcoming Vancouver concert and it offers a history dating from 2008,

MUSIC AND MEDICINE

The idea of combining music and medicine into the “Sounds & Science” – scientific concert series started in 2008, when the Austrian violinist Rainer Honeck played Bach’s Chaconne in d-minor directly before a keynote lecture, held by Nobel laureate Peter Doherty, at the Austrian Society of Allergology and Immunology’s yearly meeting in Vienna. The experience at that lecture was remarkable, truly a special moment. “Sounds & Science” was then taken a step further by bringing several concepts together: Anton Neumayr’s medical histories of composers, John Brockman’s idea of a “Third Culture” (very broadly speaking: combining humanities and science), and finally, our perception that science deserves a “Red Carpet” to walk on, in front of an audience. Attendees of the “Sounds & Science” series have also described that music opens the mind, and enables a better understanding of concepts in life and thereby science in general. On a typical concert/lecture, we start with a chamber music piece, continue with the pathobiography of the composer, go back to the music, and then introduce our main speaker, whose talk should be genuinely understandable to a broad, not necessarily scientifically trained audience. In the second half, we usually try to present a musical climax. One prerequisite that “Sounds & Science” stands for, is the outstanding quality of the principal musicians, and of the main speakers. Our previous concerts/lectures have so far covered several aspects of medicine like “Music & Cancer” (Debussy, Brahms, Schumann), “Music and Heart” (Bruckner, Mahler, Wagner), and “Music and Diabetes” (Bach, Ysaÿe, Puccini). For many individuals who have combined music and medicine or music and science inside of their own lives and biographies, the experience of a cross-connection between sounds and science is quite familiar. But there is also this “fun” aspect of sharing and participating, and at the “Sounds & Science” events, we usually try to ensure that the event location can easily be turned into a meeting place.

At a guess, Science and Sounds started informally in 2008 and became a formal series in 2014.

There is a video but it’s in German. It’s enjoyable viewing with beautiful music but unless you have German language skills you won’t get the humour. Also it runs for over 9 minutes (a little longer than most of videos you’ll find here on FrogHeart),

Enjoy!

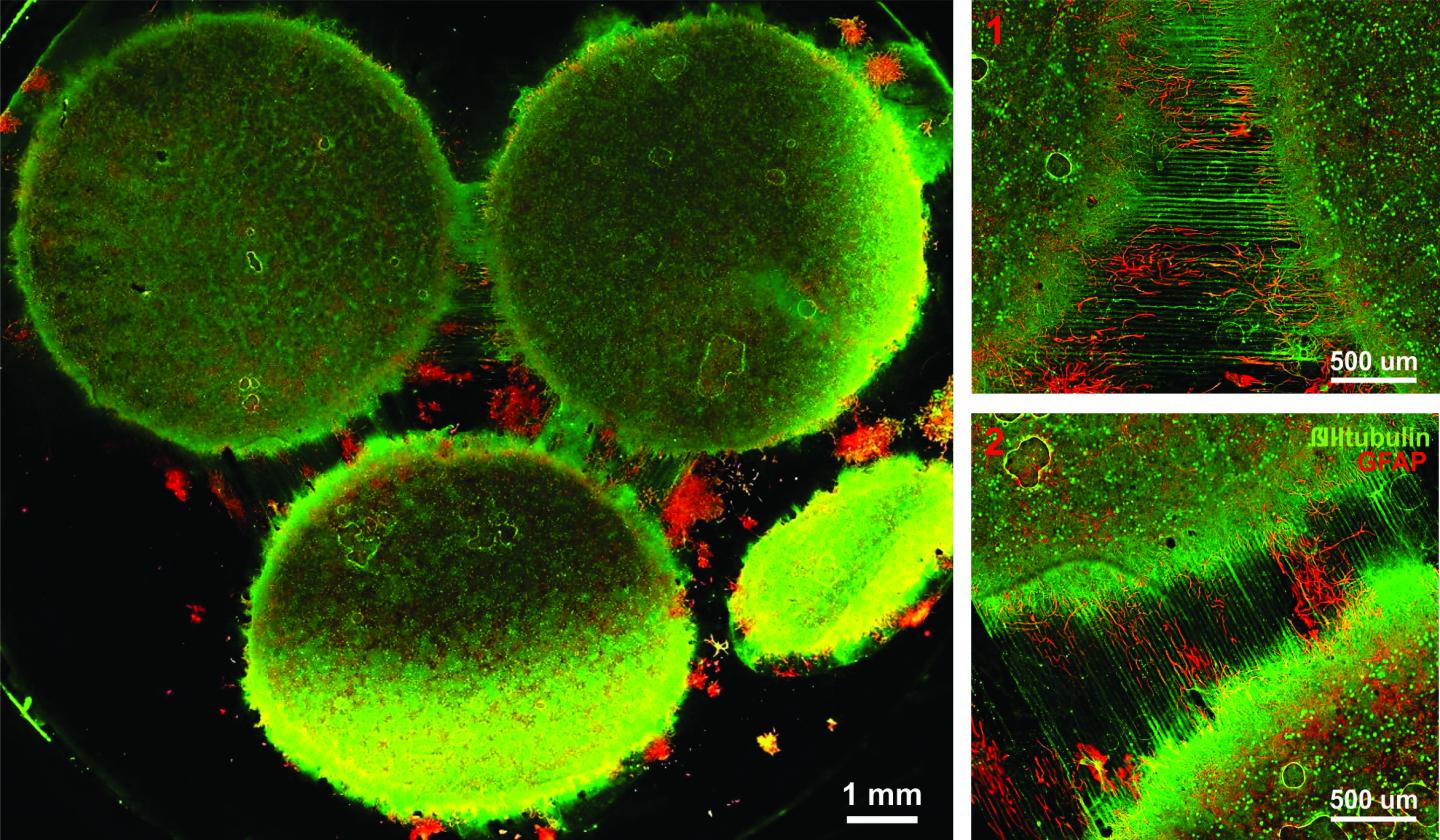

A hippocampal interneuron. Image: Biosciences Imaging Gp, Soton, Wellcome Trust via Creative Commons

A hippocampal interneuron. Image: Biosciences Imaging Gp, Soton, Wellcome Trust via Creative Commons