In response to having created a multiregional brain-on-a-chip, there’s an explanation from the team at Harvard University (which answers my question) in a Jan. 13, 2017 Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences news release (also on EurekAlert) by Leah Burrows,

Harvard University researchers have developed a multiregional brain-on-a-chip that models the connectivity between three distinct regions of the brain. The in vitro model was used to extensively characterize the differences between neurons from different regions of the brain and to mimic the system’s connectivity.

…

“The brain is so much more than individual neurons,” said Ben Maoz, co-first author of the paper and postdoctoral fellow in the Disease Biophysics Group in the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS). “It’s about the different types of cells and the connectivity between different regions of the brain. When modeling the brain, you need to be able to recapitulate that connectivity because there are many different diseases that attack those connections.”

“Roughly twenty-six percent of the US healthcare budget is spent on neurological and psychiatric disorders,” said Kit Parker, the Tarr Family Professor of Bioengineering and Applied Physics Building at SEAS and Core Faculty Member of the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University. “Tools to support the development of therapeutics to alleviate the suffering of these patients is not only the human thing to do, it is the best means of reducing this cost.”

Researchers from the Disease Biophysics Group at SEAS and the Wyss Institute modeled three regions of the brain most affected by schizophrenia — the amygdala, hippocampus and prefrontal cortex.

They began by characterizing the cell composition, protein expression, metabolism, and electrical activity of neurons from each region in vitro.

“It’s no surprise that neurons in distinct regions of the brain are different but it is surprising just how different they are,” said Stephanie Dauth, co-first author of the paper and former postdoctoral fellow in the Disease Biophysics Group. “We found that the cell-type ratio, the metabolism, the protein expression and the electrical activity all differ between regions in vitro. This shows that it does make a difference which brain region’s neurons you’re working with.”

Next, the team looked at how these neurons change when they’re communicating with one another. To do that, they cultured cells from each region independently and then let the cells establish connections via guided pathways embedded in the chip.

The researchers then measured cell composition and electrical activity again and found that the cells dramatically changed when they were in contact with neurons from different regions.

“When the cells are communicating with other regions, the cellular composition of the culture changes, the electrophysiology changes, all these inherent properties of the neurons change,” said Maoz. “This shows how important it is to implement different brain regions into in vitro models, especially when studying how neurological diseases impact connected regions of the brain.”

To demonstrate the chip’s efficacy in modeling disease, the team doped different regions of the brain with the drug Phencyclidine hydrochloride — commonly known as PCP — which simulates schizophrenia. The brain-on-a-chip allowed the researchers for the first time to look at both the drug’s impact on the individual regions as well as its downstream effect on the interconnected regions in vitro.

The brain-on-a-chip could be useful for studying any number of neurological and psychiatric diseases, including drug addiction, post traumatic stress disorder, and traumatic brain injury.

“To date, the Connectome project has not recognized all of the networks in the brain,” said Parker. “In our studies, we are showing that the extracellular matrix network is an important part of distinguishing different brain regions and that, subsequently, physiological and pathophysiological processes in these brain regions are unique. This advance will not only enable the development of therapeutics, but fundamental insights as to how we think, feel, and survive.”

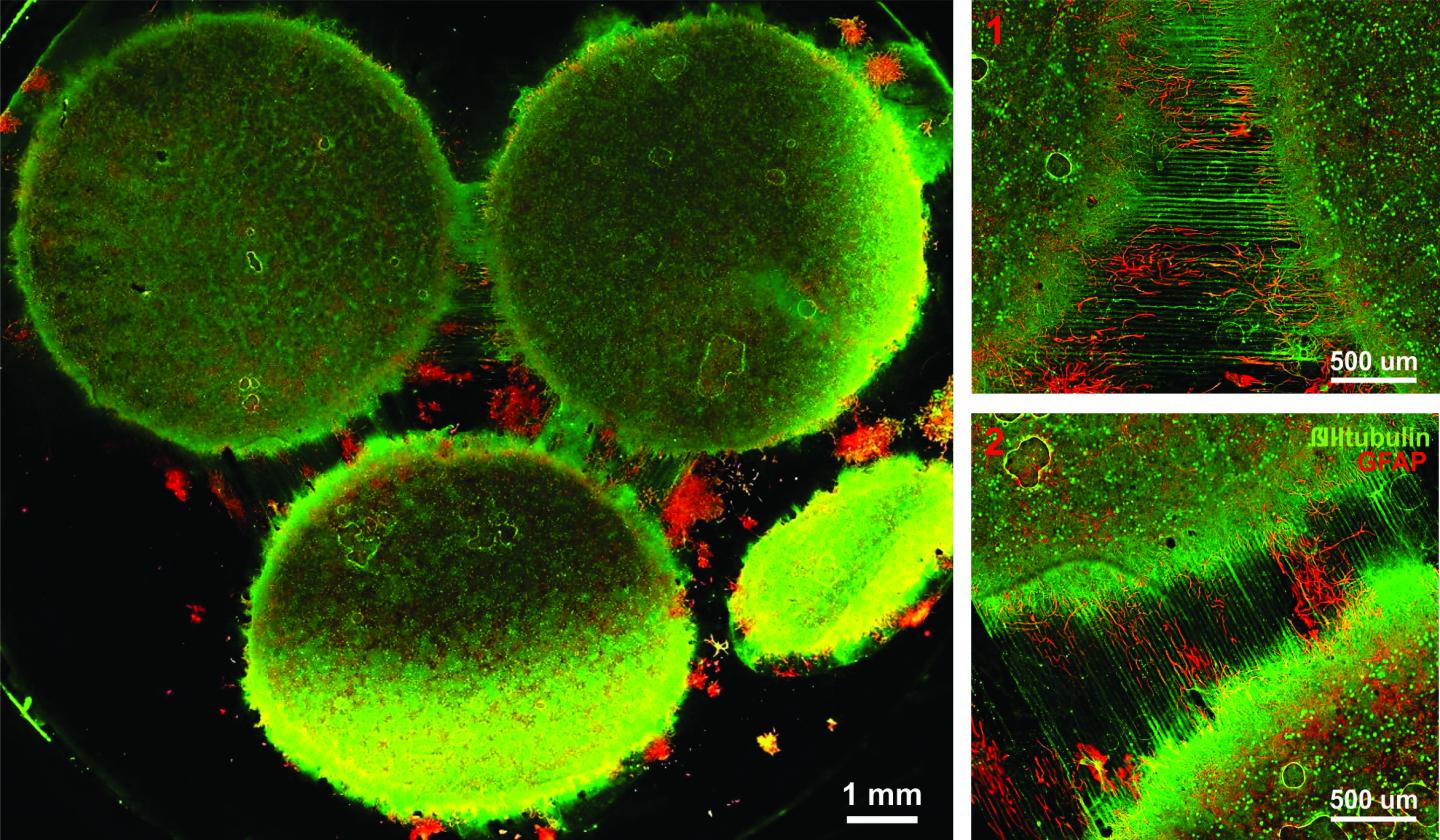

Here’s an image from the researchers,

Caption: Image of the in vitro model showing three distinct regions of the brain connected by axons. Credit: Disease Biophysics Group/Harvard University

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Neurons derived from different brain regions are inherently different in vitro: A novel multiregional brain-on-a-chip by Stephanie Dauth, Ben M Maoz, Sean P Sheehy, Matthew A Hemphill, Tara Murty, Mary Kate Macedonia, Angie M Greer, Bogdan Budnik, Kevin Kit Parker. Journal of Neurophysiology Published 28 December 2016 Vol. no. [?] , DOI: 10.1152/jn.00575.2016

This paper is behind a paywall and they haven’t included the vol. no. in the citation I’ve found.

![Schematic comparing a healthy airway (few immune cells, normal airway diameter) to an asthmatic airway (many immune cells, constricted airway). Credit: Harvard's Wyss Institute and Harvard SEAS [School of Engineering and Applied Sciences]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/AsthmaAirways-300x131.jpg)