A March 1, 2018 news item on Nanowerk announces a new coupling,

Scientists combined buckyballs, [also known as buckminsterfullerenes, fullerenes, or C60] which resemble tiny soccer balls made from 60 carbon atoms, with graphene, a single layer of carbon, on an underlying surface. Positive and negative charges can transfer between the balls and graphene depending on the nature of the surface as well as the structural order and local orientation of the carbon ball. Scientists can use this architecture to develop tunable junctions for lightweight electronic devices.

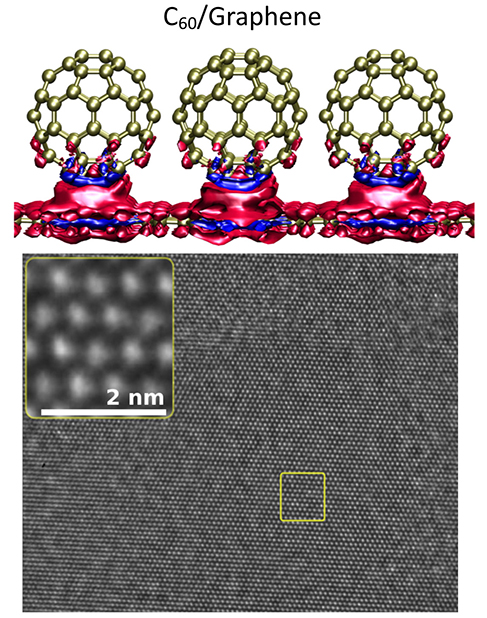

The researchers have made this illustration of their work available,

Researchers are developing new, lightweight electronics that rapidly conduct electricity by covering a sheet of carbon (graphene) with buckyballs. Electricity is the flow of electrons. On these lightweight structures, electrons as well as positive holes (missing electrons) transfer between the balls and graphene. The team showed that the crystallinity and orientation of the balls, as well as the underlying layer, affected this charge transfer. The top image shows a calculation of the charge density for a specific orientation of the balls on graphene. The blue represents positive charges, while the red is negative. The bottom image shows that the balls are in a close-packed structure. The bright dots correspond to the projected images of columns of buckyball molecules. Courtesy: US Department of Energy Office of Science

A February 28, 2018 US Department of Energy (DoE) Office of Science news release, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

The Impact

Fast-moving electrons and their counterpart, holes, were preserved in graphene with crystalline buckyball overlayers. Significantly, the carbon ball provides charge transfer to the graphene. Scientists expect the transfer to be highly tunable with external voltages. This marriage has ramifications for smart electronics that run longer and do not break as easily, bringing us closer to sensor-embedded smart clothing and robotic skin.

Summary

Charge transfer at the interface between dissimilar materials is at the heart of almost all electronic technologies such as transistors and photovoltaic devices. In this study, scientists studied charge transfer at the interface region of buckyball molecules deposited on graphene, with and without a supporting substrate, such as hexagonal boron nitride. They employed ab initio density functional theory with van der Waals interactions to model the structure theoretically. Van der Waals interactions are weak connections between neutral molecules. The team used high-resolution transmission electron microscopy and electronic transport measurements to characterize experimentally the properties of the interface. The researchers observed that charge transfer between buckyballs and the graphene was sensitive to the nature of the underlying substrate, in addition, to the crystallinity and local orientation of the buckyballs. These studies open an avenue to devices where buckyball layers on top of graphene can serve as electron acceptors and other buckyball layers as electron donors. Even at room temperature, buckyball molecules were orientationally locked into position. This is in sharp contrast to buckyball molecules in un-doped bulk crystalline configurations, where locking occurs only at low temperature. High electron and hole mobilities are preserved in graphene with crystalline buckyball overlayers. This finding has ramifications for the development of organic high-mobility field-effect devices and other high mobility applications.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Molecular Arrangement and Charge Transfer in C60 /Graphene Heterostructures by Claudia Ojeda-Aristizabal, Elton J. G. Santos, Seita Onishi, Aiming Yan, Haider I. Rasool, Salman Kahn, Yinchuan Lv, Drew W. Latzke, Jairo Velasco Jr., Michael F. Crommie, Matthew Sorensen, Kenneth Gotlieb, Chiu-Yun Lin, Kenji Watanabe, Takashi Taniguchi, Alessandra Lanzara, and Alex Zettl. ACS Nano, 2017, 11 (5), pp 4686–4693 DOI: 10.1021/acsnano.7b00551 Publication Date (Web): April 24, 2017

Copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.