This is not the first time the glasswing butterfly has inspired some new technology. Lat time, it was an eye implant,

You’ll find that image and more in my May 22, 2018 posting about the eye implant. Don’t miss scrolling down to the video which features the butterfly fluttering its wings in the first few seconds.

Getting back to the glasswing butterfly’s latest act of inspiration a July 11, 2019 news item on ScienceDaily announces the work,

Glass for technologies like displays, tablets, laptops, smartphones, and solar cells need to pass light through, but could benefit from a surface that repels water, dirt, oil, and other liquids. Researchers from the University of Pittsburgh’s Swanson School of Engineering have created a nanostructure glass that takes inspiration from the wings of the glasswing butterfly to create a new type of glass that is not only very clear across a wide variety of wavelengths and angles, but is also antifogging.

A July 11, 2019 University of Pittsburgh news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more technical detail about the new glass,

The nanostructured glass has random nanostructures, like the glasswing butterfly wing, that are smaller than the wavelengths of visible light. This allows the glass to have a very high transparency of 99.5% when the random nanostructures are on both sides of the glass. This high transparency can reduce the brightness and power demands on displays that could, for example, extend battery life. The glass is antireflective across higher angles, improving viewing angles. The glass also has low haze, less than 0.1%, which results in very clear images and text.

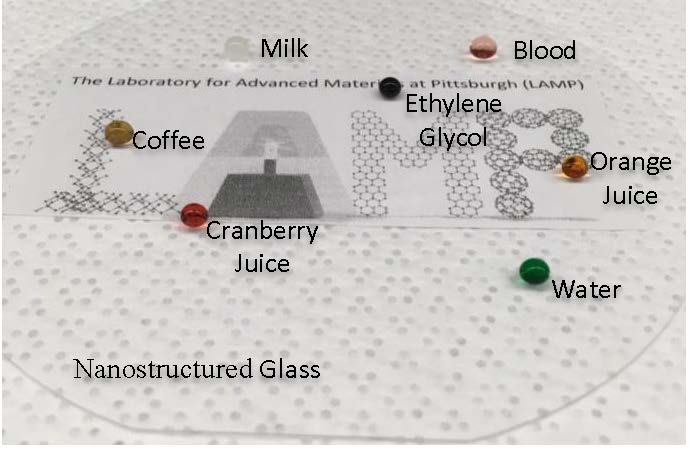

“The glass is superomniphobic, meaning it repels a wide variety of liquids such as orange juice, coffee, water, blood, and milk,” explains Sajad Haghanifar, lead author of the paper and doctoral candidate in industrial engineering at Pitt. “The glass is also anti-fogging, as water condensation tends to easily roll off the surface, and the view through the glass remains unobstructed. Finally, the nanostructured glass is durable from abrasion due to its self-healing properties–abrading the surface with a rough sponge damages the coating, but heating it restores it to its original function.”

Natural surfaces like lotus leaves, moth eyes and butterfly wings display omniphobic properties that make them self-cleaning, bacterial-resistant and water-repellant–adaptations for survival that evolved over millions of years. Researchers have long sought inspiration from nature to replicate these properties in a synthetic material, and even to improve upon them. While the team could not rely on evolution to achieve these results, they instead utilized machine learning.

“Something significant about the nanostructured glass research, in particular, is that we partnered with SigOpt to use machine learning to reach our final product,” says Paul Leu, PhD, associate professor of industrial engineering, whose lab conducted the research. Dr. Leu holds secondary appointments in mechanical engineering and materials science and chemical engineering. “When you create something like this, you don’t start with a lot of data, and each trial takes a great deal of time. We used machine learning to suggest variables to change, and it took us fewer tries to create this material as a result.”

“Bayesian optimization and active search are the ideal tools to explore the balance between transparency and omniphobicity efficiently, that is, without needing thousands of fabrications, requiring hundreds of days.” said Michael McCourt, PhD, research engineer at SigOpt. Bolong Cheng, PhD, fellow research engineer at SigOpt, added, “Machine learning and AI strategies are only relevant when they solve real problems; we are excited to be able to collaborate with the University of Pittsburgh to bring the power of Bayesian active learning to a new application.”

Here’s an image illustrating the work from the researchers,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Creating glasswing butterfly-inspired durable antifogging superomniphobic supertransmissive, superclear nanostructured glass through Bayesian learning and optimization by Sajad Haghanifar, Michael McCourt, Bolong Cheng, Jeffrey Wuenschell, Paul Ohodnickic, and Paul W. Leu. Mater. Horiz., 2019, Advance Article DOI: 10.1039/C9MH00589G first published on 10 Jun 2019

This paper is behind a paywall. One more thing, here’s SigOpt, the company the scientists partnered.

![Subsea installations can get longer life-time with self-repairing materials. Illustration: SINTEF Energy [downloaded from http://gemini.no/en/2014/11/self-repairing-subsea-material/]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/SubseaInstallation-300x150.png)