While discussions of gecko lizards in the ‘nanotechnology world’ are almost always focused on the creature’s adhesive properties, a recent research article in Physical Review E explores the gecko’s ‘loss of grip’. From a July 9, 2014 news item on Nanowerk (Note: A link has been removed),

Geckos and spiders that seem to be able to sit still forever, and walk around upside down have fascinated researchers worldwide for many years. We will soon be able to buy smart new fasteners that hold the same way as the gecko’s foot. But the fact is, sooner or later the grip is lost, no matter how little force is acting on it. Stefan Lindström and Lars Johansson, researchers at the Division of Mechanics, Linköping University, together with Nils Karlsson, recent engineering graduate, have demonstrated this in an article just published in Physical Review E (“Metastable states and activated dynamics in thin-film adhesion to patterned surfaces”).

A June 24, 2014 Linköping University press release (also on EurekAlert but dated July 9, 2014), which originated the news item, describes how this ‘grip loss’ could have implications for graphene production,

…, it’s a phenomenon that can have considerable benefits, for instance in the production of graphene. Graphene consists only of one layer of atom, and which must be easily detached from the substrate.

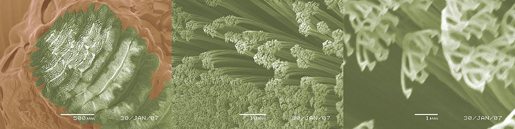

In his graduation project at the Division of Mechanics, Nils Karlsson studied both the mechanics of the gecko’s leg as well as the adhesion of its foot to the substrate. The gecko’s foot has five toes, all with transverse lamellae. A scanning electron microscope shows that these lamellae consist of a number of small hair-like setae, each with a little film at the end, which resembles a small spatula. These spatulae, roughly 10 nm thick, are what adheres to the substrate.

”At the nano level, conditions are a bit different. The movement of the molecules is negligible in our macroscopic world, but it’s not in the nano world. Nils Karlsson’s graduation project suggested that heat, and consequently the movement of the molecules, has an effect on the adhesion of these spatulae. We wanted to do further analyses, and calculate what actually happens,” explains Stefan Lindström.

They refined the calculations, so they applied to a thin film in contact with an uneven surface (…). So, the film only contacts the uppermost parts of the uneven surface. The researchers also chose to limit the calculations to the type of weak forces that exist between all atoms and molecules – van der Waals forces.

”It’s true, they are small, but they are always there and we know that they are extremely reliant on distance,” says Lars Johansson.

This means that the force is much stronger where the film is very close to a single high point, than when it is quite close to a number of high points. Then, when the film detaches, it does this point by point. This is because both contact surfaces are moving – vibrating. These are tiny movements, but at some stage the movements are in sync, so the surfaces actually lose contact. Then the van der Waals force is so small that the film releases.

”So in reality, we can detach a thin film from the substrate simply by waiting for the right moment. This doesn’t require a great deal of force. The part of the film that remains on the substrate vibrates constantly, and the harder I pull on this part, the faster the film will detach. But how long it takes for the film to detach also depends on the structure of the substrate and the film’s stiffness,” says Stefan Lindström.

In practice this means that even a small force over a long period will cause the film, or for that matter the gecko’s foot, to lose its grip. Which is fine for the gecko, who can scoot off, but maybe not so good for a fastening system. Still – in the right application, this knowledge can be of great industrial benefit.

This is what a gecko’s foot looks like when viewed through a scanning electron microscope,

The pictures of the gecko’s foot is taken by Oskar Geller, Lund University, with a scanning electron microscope. Linköping University

The image looks like a candidate for entry into a nano art show.

Here’s a link to and citation for the paper,

Metastable states and activated dynamics in thin-film adhesion to patterned surfaces by Stefan B. Lindström, Lars Johansson, and Nils R. Karlsson. DOI 10.1103/PhysRevE.89.062401 Phys. Rev. E 89, 062401 – Published 6 June 2014

This paper is behind a paywall.

Kudos to anyone who recognized the paraphrasing of the song title, ‘Catch a falling star’ in the head for this posting,