There’s a possibility that in the future, artificial neurons could be used for medical treatment according to a January 12, 2023 news item on phys.org,

Researchers at Linköping University (LiU), Sweden, have created an artificial organic neuron that closely mimics the characteristics of biological nerve cells. This artificial neuron can stimulate natural nerves, making it a promising technology for various medical treatments in the future.

Work to develop increasingly functional artificial nerve cells continues at the Laboratory for Organic Electronics, LOE. In 2022, a team of scientists led by associate professor Simone Fabiano demonstrated how an artificial organic neuron could be integrated into a living carnivorous plant [emphasis mine] to control the opening and closing of its maw. This synthetic nerve cell met two of the 20 characteristics that differentiate it from a biological nerve cell.

…

I wasn’t expecting a carnivorous plant, living or otherwise. Sadly, they don’t seem to have been able to include it in this image although the ‘green mitts’ are evocative,

A January 13, 2023 Linköping University (LiU) press release by Mikael Sönne (also on EurkeAlert but published January 12, 2023), which originated the news item, delves further into the work,

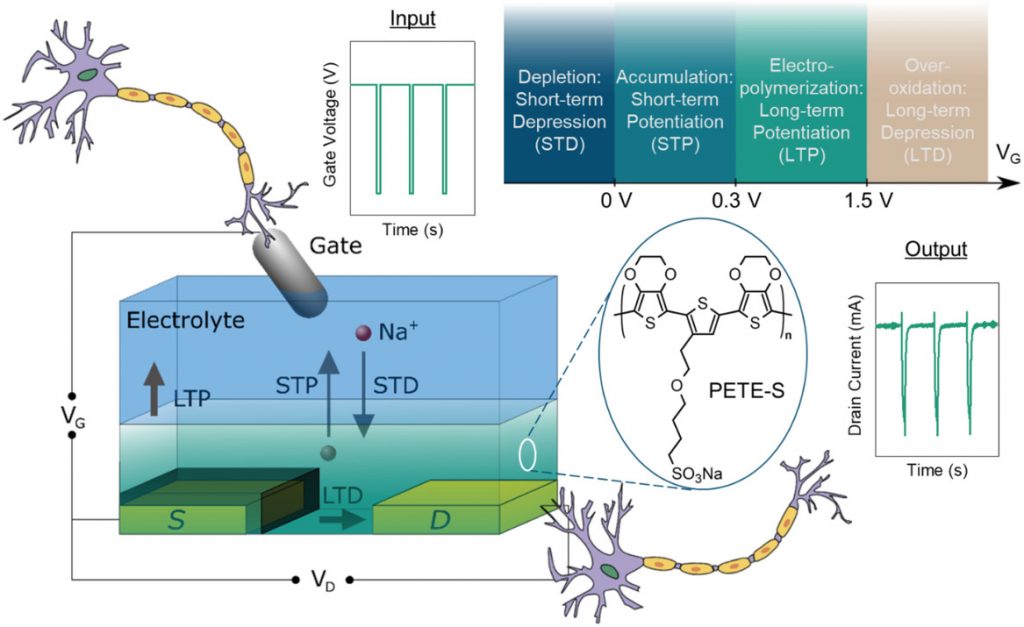

In their latest study, published in the journal Nature Materials, the same researchers at LiU have developed a new artificial nerve cell called “conductance-based organic electrochemical neuron” or c-OECN, which closely mimics 15 out of the 20 neural features that characterise biological nerve cells, making its functioning much more similar to natural nerve cells.

“One of the key challenges in creating artificial neurons that effectively mimic real biological neurons is the ability to incorporate ion modulation. Traditional artificial neurons made of silicon can emulate many neural features but cannot communicate through ions. In contrast, c-OECNs use ions to demonstrate several key features of real biological neurons”, says Simone Fabiano, principal investigator of the Organic Nanoelectronics group at LOE.

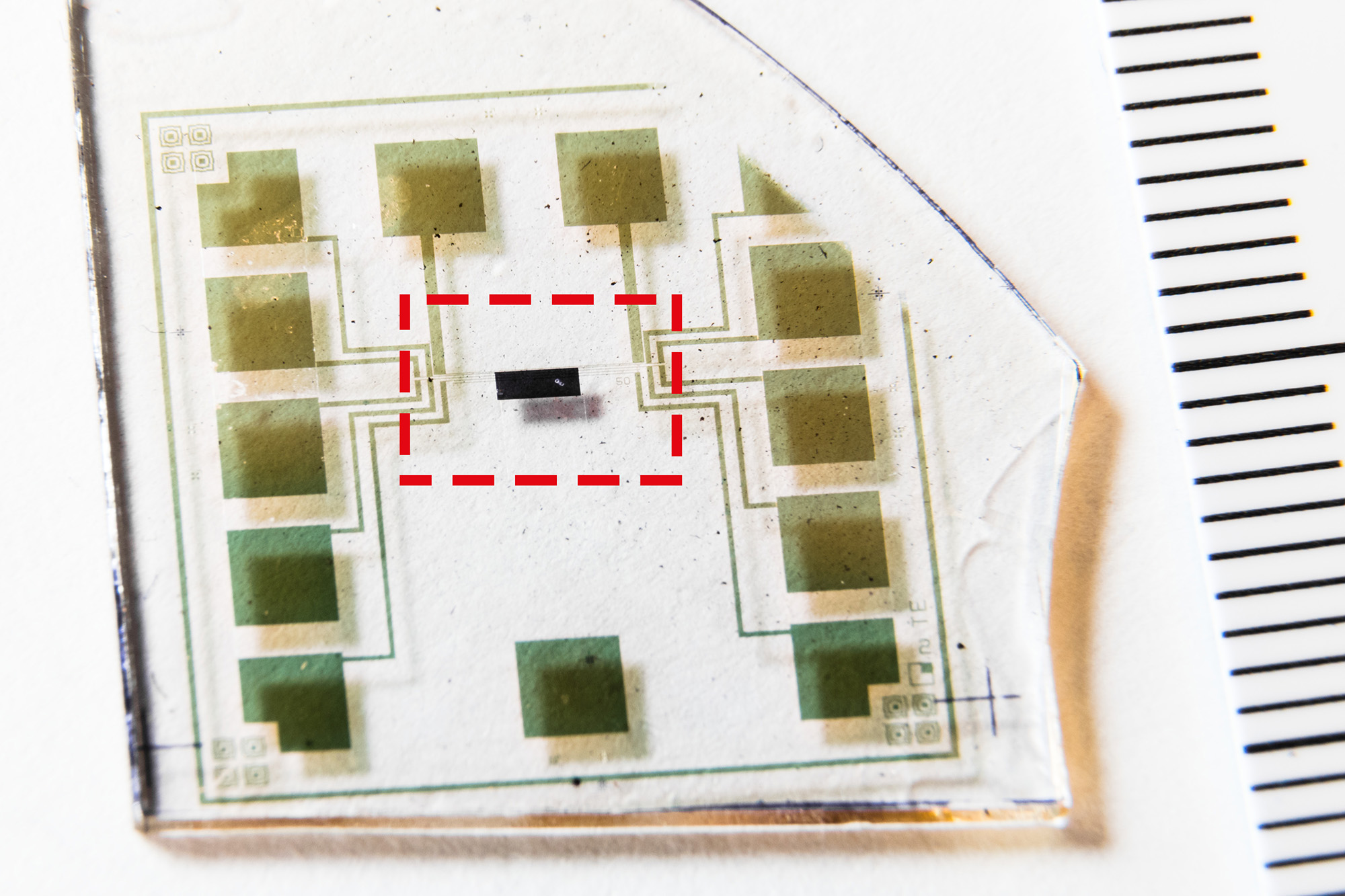

In 2018, this research group at Linköping University was one of the first to develop organic electrochemical transistors based on n-type conducting polymers, which are materials that can conduct negative charges. This made it possible to build printable complementary organic electrochemical circuits. Since then, the group has been working to optimise these transistors so that they can be printed in a printing press on a thin plastic foil. As a result, it is now possible to print thousands of transistors on a flexible substrate and use them to develop artificial nerve cells.

In the newly developed artificial neuron, ions are used to control the flow of electronic current through an n-type conducting polymer, leading to spikes in the device’s voltage. This process is similar to that which occurs in biological nerve cells. The unique material in the artificial nerve cell also allows the current to be increased and decreased in an almost perfect bell-shaped curve that resembles the activation and inactivation of sodium ion channels found in biology.

“Several other polymers show this behaviour, but only rigid polymers are resilient to disorder, enabling stable device operation”, says Simone Fabiano

In experiments carried out in collaboration with Karolinska Institute (KI), the new c-OECN neurons were connected to the vagus nerve of mice. The results show that the artificial neuron could stimulate the mice’s nerves, causing a 4.5% change in their heart rate.

The fact that the artificial neuron can stimulate the vagus nerve itself could, in the long run, pave the way for essential applications in various forms of medical treatment. In general, organic semiconductors have the advantage of being biocompatible, soft, and malleable, while the vagus nerve plays a key role, for example, in the body’s immune system and metabolism.

The next step for the researchers will be to reduce the energy consumption of the artificial neurons, which is still much higher than that of human nerve cells. Much work remains to be done to replicate nature artificially.

“There is much we still don’t fully understand about the human brain and nerve cells. In fact, we don’t know how the nerve cell makes use of many of these 15 demonstrated features. Mimicking the nerve cells can enable us to understand the brain better and build circuits capable of performing intelligent tasks. We’ve got a long road ahead, but this study is a good start,” says Padinhare Cholakkal Harikesh, postdoc and main author of the scientific paper.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Ion-tunable antiambipolarity in mixed ion–electron conducting polymers enables biorealistic organic electrochemical neurons by Padinhare Cholakkal Harikesh, Chi-Yuan Yang, Han-Yan Wu, Silan Zhang, Mary J. Donahue, April S. Caravaca, Jun-Da Huang, Peder S. Olofsson, Magnus Berggren, Deyu Tu & Simone Fabiano. Nature Materials volume 22, pages 242–248 (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41563-022-01450-8 Published online: 12 January 2023 Issue Date: February 2023

This paper is open access.