An August 15 ,2022 news item on ScienceDaily announces a type of guide for memristive hardware design,

They are many times faster than flash memory and require significantly less energy: memristive memory cells could revolutionize the energy efficiency of neuromorphic [brainlike] computers. In these computers, which are modeled on the way the human brain works, memristive cells function like artificial synapses. Numerous groups around the world are working on the use of corresponding neuromorphic circuits — but often with a lack of understanding of how they work and with faulty models. Jülich researchers have now summarized the physical principles and models in a comprehensive review article in the renowned journal Advances in Physics.

…

An August 15, 2022 Forschungszentrum Juelich press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes two papers designed to help researchers better understand and design memristive hardware,

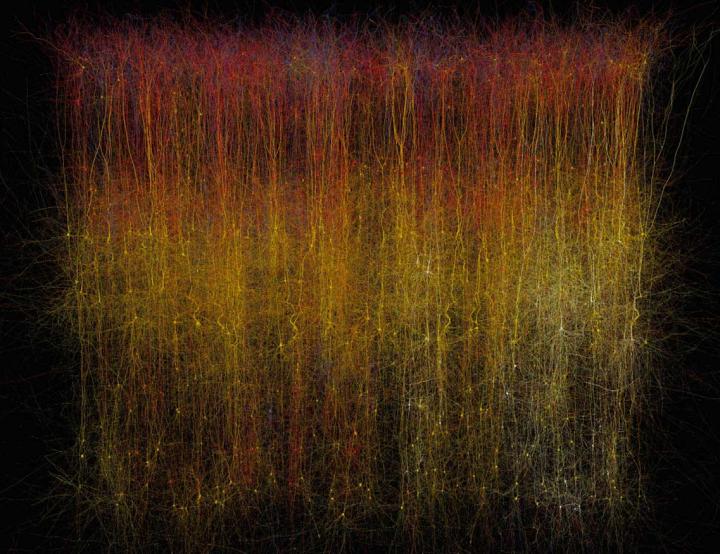

Certain tasks – such as recognizing patterns and language – are performed highly efficiently by a human brain, requiring only about one ten-thousandth of the energy of a conventional, so-called “von Neumann” computer. One of the reasons lies in the structural differences: In a von Neumann architecture, there is a clear separation between memory and processor, which requires constant moving of large amounts of data. This is time and energy consuming – the so-called von Neumann bottleneck. In the brain, the computational operation takes place directly in the data memory and the biological synapses perform the tasks of memory and processor at the same time.

In Jülich, scientists have been working for more than 15 years on special data storage devices and components that can have similar properties to the synapses in the human brain. So-called memristive memory devices, also known as memristors, are considered to be extremely fast, energy-saving and can be miniaturized very well down to the nanometer range. The functioning of memristive cells is based on a very special effect: Their electrical resistance is not constant, but can be changed and reset again by applying an external voltage, theoretically continuously. The change in resistance is controlled by the movement of oxygen ions. If these move out of the semiconducting metal oxide layer, the material becomes more conductive and the electrical resistance drops. This change in resistance can be used to store information.

The processes that can occur in cells are very complex and vary depending on the material system. Three researchers from the Jülich Peter Grünberg Institute – Prof. Regina Dittmann, Dr. Stephan Menzel, and Prof. Rainer Waser – have therefore compiled their research results in a detailed review article, “Nanoionic memristive phenomena in metal oxides: the valence change mechanism”. They explain in detail the various physical and chemical effects in memristors and shed light on the influence of these effects on the switching properties of memristive cells and their reliability.

“If you look at current research activities in the field of neuromorphic memristor circuits, they are often based on empirical approaches to material optimization,” said Rainer Waser, director at the Peter Grünberg Institute. “Our goal with our review article is to give researchers something to work with in order to enable insight-driven material optimization.” The team of authors worked on the approximately 200-page article for ten years and naturally had to keep incorporating advances in knowledge.

“The analogous functioning of memristive cells required for their use as artificial synapses is not the normal case. Usually, there are sudden jumps in resistance, generated by the mutual amplification of ionic motion and Joule heat,” explains Regina Dittmann of the Peter Grünberg Institute. “In our review article, we provide researchers with the necessary understanding of how to change the dynamics of the cells to enable an analog operating mode.”

“You see time and again that groups simulate their memristor circuits with models that don’t take into account high dynamics of the cells at all. These circuits will never work.” said Stephan Menzel, who leads modeling activities at the Peter Grünberg Institute and has developed powerful compact models that are now in the public domain (www.emrl.de/jart.html). “In our review article, we provide the basics that are extremely helpful for a correct use of our compact models.”

Roadmap neuromorphic computing

The “Roadmap of Neuromorphic Computing and Engineering”, which was published in May 2022, shows how neuromorphic computing can help to reduce the enormous energy consumption of IT globally. In it, researchers from the Peter Grünberg Institute (PGI-7), together with leading experts in the field, have compiled the various technological possibilities, computational approaches, learning algorithms and fields of application.

According to the study, applications in the field of artificial intelligence, such as pattern recognition or speech recognition, are likely to benefit in a special way from the use of neuromorphic hardware. This is because they are based – much more so than classical numerical computing operations – on the shifting of large amounts of data. Memristive cells make it possible to process these gigantic data sets directly in memory without transporting them back and forth between processor and memory. This could reduce the energy efficiency of artificial neural networks by orders of magnitude.

Memristive cells can also be interconnected to form high-density matrices that enable neural networks to learn locally. This so-called edge computing thus shifts computations from the data center to the factory floor, the vehicle, or the home of people in need of care. Thus, monitoring and controlling processes or initiating rescue measures can be done without sending data via a cloud. “This achieves two things at the same time: you save energy, and at the same time, personal data and data relevant to security remain on site,” says Prof. Dittmann, who played a key role in creating the roadmap as editor.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the ‘roadmap’,

2022 roadmap on neuromorphic computing and engineering by Dennis V Christensen, Regina Dittmann, Bernabe Linares-Barranco, Abu Sebastian, Manuel Le Gallo, Andrea Redaelli, Stefan Slesazeck, Thomas Mikolajick, Sabina Spiga, Stephan Menzel, Ilia Valov, Gianluca Milano, Carlo Ricciardi, Shi-Jun Liang, Feng Miao, Mario Lanza, Tyler J Quill, Scott T Keene, Alberto Salleo, Julie Grollier, Danijela Marković, Alice Mizrahi, Peng Yao, J Joshua Yang, Giacomo Indiveri, John Paul Strachan, Suman Datta, Elisa Vianello, Alexandre Valentian, Johannes Feldmann, Xuan Li, Wolfram H P Pernice, Harish Bhaskaran, Steve Furber, Emre Neftci, Franz Scherr, Wolfgang Maass, Srikanth Ramaswamy, Jonathan Tapson, Priyadarshini Panda, Youngeun Kim, Gouhei Tanaka, Simon Thorpe, Chiara Bartolozzi, Thomas A Cleland, Christoph Posch, ShihChii Liu, Gabriella Panuccio, Mufti Mahmud, Arnab Neelim Mazumder, Morteza Hosseini, Tinoosh Mohsenin, Elisa Donati, Silvia Tolu, Roberto Galeazzi, Martin Ejsing Christensen, Sune Holm, Daniele Ielmini and N Pryds. Neuromorphic Computing and Engineering , Volume 2, Number 2 DOI: 10.1088/2634-4386/ac4a83 20 May 2022 • © 2022 The Author(s)

This paper is open access.

Here’s the most recent paper,

Nanoionic memristive phenomena in metal oxides: the valence change mechanism by Regina Dittmann, Stephan Menzel & Rainer Waser. Advances in Physics

Volume 70, 2021 – Issue 2 Pages 155-349 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00018732.2022.2084006 Published online: 06 Aug 2022

This paper is behind a paywall.