Amazingly lifelike, eh, and nothing like what you see in James Cameron’s Avatar movies,

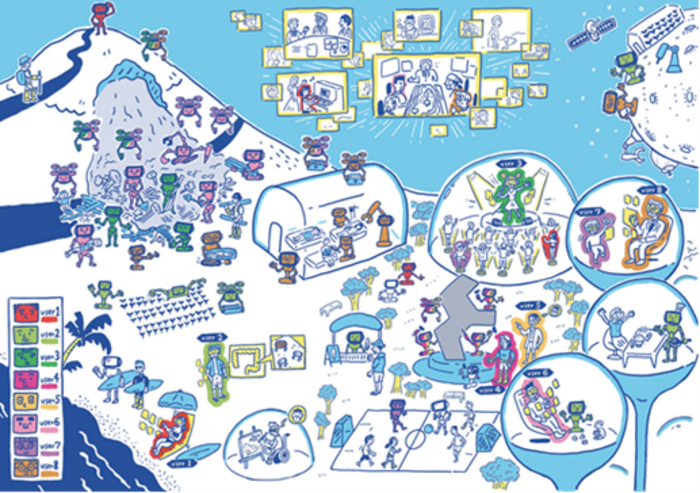

Before getting to the press release, this image’s caption helps to explain what Japan’s government wants to accomplish,

An October 21, 2022 Japan Science and Technology Agency press release (also on EurekAlert but published November 16, 2022) announces Japan’s Minister of Digital Affairs’ cybernetic avatar (or you could call it a robot),

The use of cybernetic avatars(1) (CAs) will allow their operators to take part in social activities without being physically present at a particular location, thereby enhancing the efficiency of business operations. Further productivity increases will be achieved if a single individual operates multiple avatars. For operations that must be carried out by a designated person (e.g., those in which a designated responsible party must provide some explanation), a CA that closely resembles the individual will create the impression that they are on site, allowing work to be carried out remotely. However, a CA closely resembling the operator may be equated with the individual, even when it is operated by a different person or by artificial intelligence. To realize the use of CAs within social activities, problems related to their “identity” must be taken into consideration: that is, whether perceiving the doings of a CA as the same as those of its operator is acceptable. Such problems should be considered not only by specialists engaged in the design of social systems but also by those experienced with using CAs.

As part of the Moonshot Research and Development Program lead by the Cabinet Office and promoted by the Japan Science and Technology Agency, the group lead by Takahiro Miyashita, director of the Interaction Science Laboratory at Advanced Telecommunications Research Institute International (ATR), and Professor Hiroshi Ishiguro of the Osaka University Graduate School of Engineering Science are aiming to create highly hospitable CAs capable of moral discourse and conduct; they will conduct a proof-of-concept test using a government minister’s CA to determine the norms for a CA society.

The current project will seek to undertake a proof-of-concept test using the CA of Taro Kono, Minister of Digital Affairs, by the year-end. Using a physical CA, the test will assess whether people feel that the minister is addressing them, whether they are more receptive to what the minister is saying, among other potential effects. Further, a broad range of people will be asked to consider whether it is acceptable to equate the actions of a CA with those of its operator, to aid the determination of new social norms for a CA society.

This initiative is curried out with the cooperation of the Guardian Robot Project, Riken led by a team leader, Dr. Takashi Minato.

(1) Cybernetic Avatar: Cybernetic Avatar is a concept that includes not only remote avatars using robots and 3D images as proxies but also augmentations of physical/cognitive abilities of humans using ICT and robotics. It aims to allow for free action within the cyber-physical environment of Society 5.0. CAs may have various functions and forms that aim to remove the natural limitations of the body, brain, space, and time.

Moonshot Research and Development Program

Moonshot Goal 1: Realization of a society in which human beings can be free from limitations of body, brain, space, and time by 2050.

Program Director (PD): Hagita Norihiro, Chair and Professor, Art Science Department, Osaka University of Arts

The program will utilize a superior level of cyborg- and avatar-related technologies to promote the development of CA technologies that will expand human physical, cognitive, and perceptual abilities, while considering social acceptability. This shall be undertaken in the hope of creating a society wherein humans are liberated from the limitations of body, brain, space, and time, by 2050.

Project: The Realization of an Avatar-Symbiotic Society where Everyone can Perform Active Roles without Constraint

Project Manager: Ishiguro Hiroshi, Professor, Graduate School of Engineering Science, Osaka University

The project will see multiple highly hospitable CAs capable of moral dialogue , which act according to users’ reactions while being operated remotely, allowing for participation in a range of daily activities (work, education, healthcare and other everyday activities) without being physically present at a particular location. By the year 2050, lifestyles will have changed markedly in terms of location choice, the use of time, and the expansion of human capacities. Nonetheless, this project will seek to achieve a society wherein people and avatars coexist harmoniously.

If you want to take a look at Minister Kono and his cybernetic avatar in action (one of Hiroshi Ishiguro’s Geminoid robots) in action together, watch the embedded video in this October 25, 2022 news item on the NHK world Japan website “Humanoid replica to assist Japan minister in digital push.”

Hiroshi Ishiguro and his work have been featured here a number of times starting with a March 10, 2011 posting about Danish philosopher, Henrik Scharfe, who commissioned a Geminoid in his own image for his research. I have not been able to find any published articles about Scharfe’s work post Geminoid but that may be due to my inability to read to Danish.

The most recent previous ‘Ishiguro’ posting here is a March 27, 2017 post titled: “Ishiguro’s robots and Swiss scientist question artificial intelligence at SXSW (South by Southwest) 2017.”

![In her series “What About the Heart?,” British photographer Luisa Whitton documents one of the creepiest niches of the Japanese robotics industry--androids. Here, an eerily lifelike face made for a robot. [dowloaded from http://www.fastcodesign.com/3031125/exposure/japans-uncanny-quest-to-humanize-robots?partner=rss]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/What-About-the-Heart.jpg)