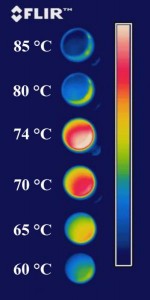

I find some illustrations a little difficult to decipher,

I believe the red in the ‘on/off’ images, signifies heat from the surrounding environment and is not an indicator for body heat and the yellow square in the ‘on’ image indicates the shirt is working and repelling that heat.

Moving on, a June 18, 2020 news item on Nanowerk describes this latest work on a smart textile that can help regulate body temperature when it’s hot,

New research on the two-dimensional (2D) material graphene has allowed researchers to create smart adaptive clothing which can lower the body temperature of the wearer in hot climates.

A team of scientists from The University of Manchester’s National Graphene Institute have created a prototype garment to demonstrate dynamic thermal radiation control within a piece of clothing by utilising the remarkable thermal properties and flexibility of graphene. The development also opens the door to new applications such as, interactive infrared displays and covert infrared communication on textiles.

A June 18, 2020 University of Manchester press release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail,

The human body radiates energy in the form of electromagnetic waves in the infrared spectrum (known as blackbody radiation). In a hot climate it is desirable to make use the full extent of the infrared radiation to lower the body temperature that can be achieved by using infrared-transparent textiles. As for the opposite case, infrared-blocking covers are ideal to minimise the energy loss from the body. Emergency blankets are a common example used to deal with treating extreme cases of body temperature fluctuation.

The collaborative team of scientists demonstrated the dynamic transition between two opposite states by electrically tuning the infrared emissivity (the ability to radiate energy) of the graphene layers integrated onto textiles.

One-atom thick graphene was first isolated and explored in 2004 at The University of Manchester. Its potential uses are vast and research has already led to leaps forward in commercial products including; batteries, mobile phones, sporting goods and automotive.

The new research published today in journal Nano Letters, demonstrates that the smart optical textile technology can change its thermal visibility. The technology uses graphene layers to control of thermal radiation from textile surfaces.

Professor Coskun Kocabas, who led the research, said: “Ability to control the thermal radiation is a key necessity for several critical applications such as temperature management of the body in excessive temperature climates. Thermal blankets are a common example used for this purpose. However, maintaining these functionalities as the surroundings heats up or cools down has been an outstanding challenge.”

Prof Kocabas added: “The successful demonstration of the modulation of optical properties on different forms of textile can leverage the ubiquitous use of fibrous architectures and enable new technologies operating in the infrared and other regions of the electromagnetic spectrum for applications including textile displays, communication, adaptive space suits, and fashion”.

This study built on the same group’s previous research using graphene to create thermal camouflage which would fool infrared cameras. The new research can also be integrated into existing mass-manufacture textile materials such as cotton. To demonstrate, the team developed a prototype product within a t-shirt allowing the wearer to project coded messages invisible to the naked eye but readable by infrared cameras.

“We believe that our results are timely showing the possibility of turning the exceptional optical properties of graphene into novel enabling technologies. The demonstrated capabilities cannot be achieved with conventional materials.”

“The next step for this area of research is to address the need for dynamic thermal management of earth-orbiting satellites. Satellites in orbit experience excesses of temperature, when they face the sun, and they freeze in the earth’s shadow. Our technology could enable dynamic thermal management of satellites by controlling the thermal radiation and regulate the satellite temperature on demand.” said Kocabas.

Professor Sir Kostya Novoselov was also involved in the research: “This is a beautiful effect, intrinsically routed in the unique band structure of graphene. It is really exciting to see that such effects give rise to the high-tech applications.” he said.

Advanced materials is one of The University of Manchester’s research beacons – examples of pioneering discoveries, interdisciplinary collaboration and cross-sector partnerships that are tackling some of the biggest questions facing the planet. #ResearchBeacons

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Graphene-Enabled Adaptive Infrared Textiles by M. Said Ergoktas, Gokhan Bakan, Pietro Steiner, Cian Bartlam, Yury Malevich, Elif Ozden-Yenigun, Guanliang He, Nazmul Karim, Pietro Cataldi, Mark A. Bissett, Ian A. Kinloch, Kostya S. Novoselov, and Coskun Kocabas. Nano Lett. 2020, XXXX, XXX, XXX-XXX DOI: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c01694 Publication Date:June 18, 2020 Copyright © 2020 American Chemical Society

This paper is behind a paywall.