Apparently this biowire derived by synthetic biology processes can make nanoelectronics a greener affair. From a July 14, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

Scientists at the University of Massachusetts Amherst report in the current issue of Small that they have genetically designed a new strain of bacteria that spins out extremely thin and highly conductive wires made up of solely of non-toxic, natural amino acids.

A July 14, 2016 University of Massachusetts at Amherst news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more information,

Researchers led by microbiologist Derek Lovley say the wires, which rival the thinnest wires known to man, are produced from renewable, inexpensive feedstocks and avoid the harsh chemical processes typically used to produce nanoelectronic materials.

Lovley says, “New sources of electronic materials are needed to meet the increasing demand for making smaller, more powerful electronic devices in a sustainable way.” The ability to mass-produce such thin conductive wires with this sustainable technology has many potential applications in electronic devices, functioning not only as wires, but also transistors and capacitors. Proposed applications include biocompatible sensors, computing devices, and as components of solar panels.

This advance began a decade ago, when Lovley and colleagues discovered that Geobacter, a common soil microorganism, could produce “microbial nanowires,” electrically conductive protein filaments that help the microbe grow on the iron minerals abundant in soil. These microbial nanowires were conductive enough to meet the bacterium’s needs, but their conductivity was well below the conductivities of organic wires that chemists could synthesize.

“As we learned more about how the microbial nanowires worked we realized that it might be possible to improve on Nature’s design,” says Lovley. “We knew that one class of amino acids was important for the conductivity, so we rearranged these amino acids to produce a synthetic nanowire that we thought might be more conductive.”

The trick they discovered to accomplish this was to introduce tryptophan, an amino acid not present in the natural nanowires. Tryptophan is a common aromatic amino acid notorious for causing drowsiness after eating Thanksgiving turkey. However, it is also highly effective at the nanoscale in transporting electrons.

“We designed a synthetic nanowire in which a tryptophan was inserted where nature had used a phenylalanine and put in another tryptophan for one of the tyrosines. We hoped to get lucky and that Geobacter might still form nanowires from this synthetic peptide and maybe double the nanowire conductivity,” says Lovley.

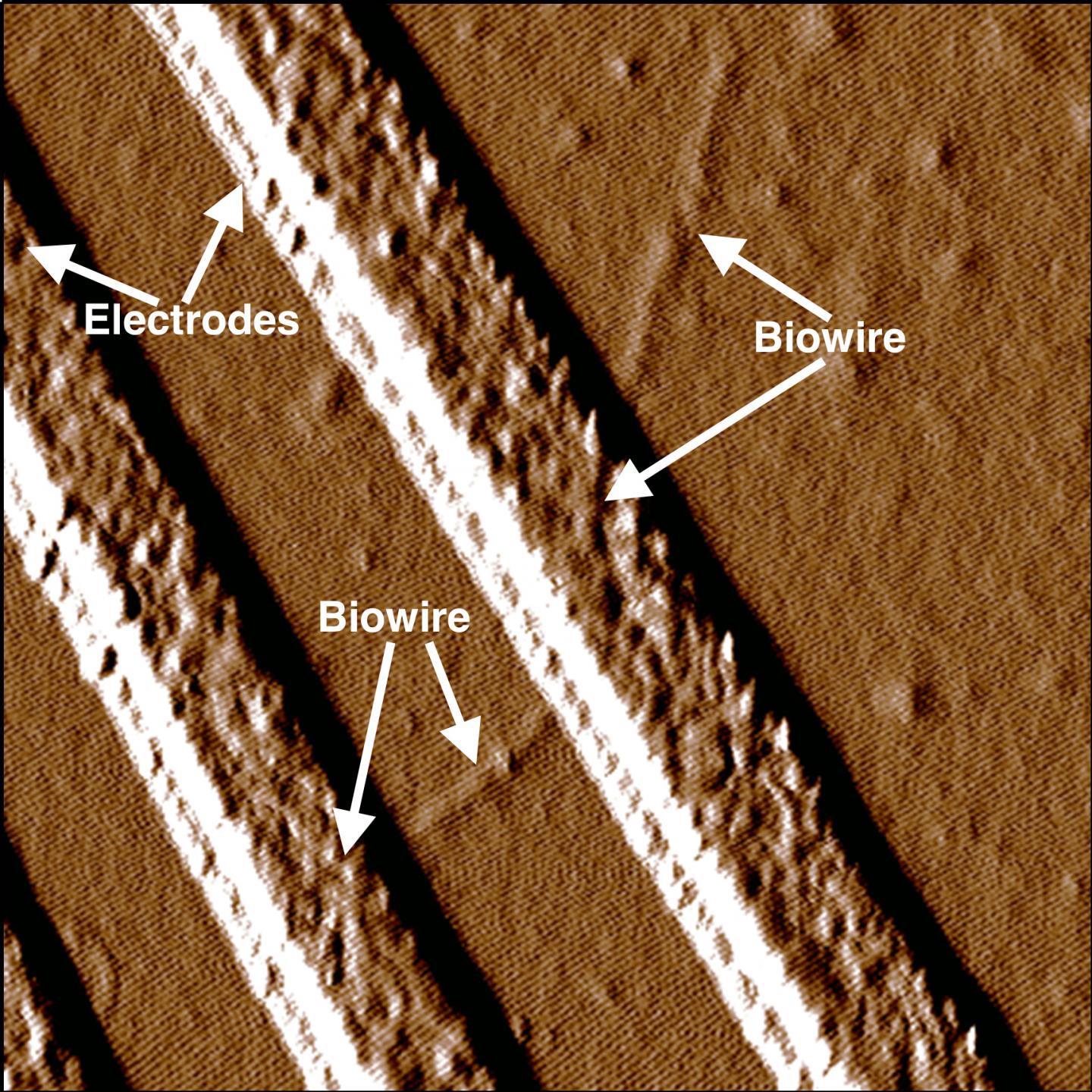

The results greatly exceeded the scientists’ expectations. They genetically engineered a strain of Geobacter and manufactured large quantities of the synthetic nanowires 2000 times more conductive than the natural biological product. An added bonus is that the synthetic nanowires, which Lovley refers to as “biowire,” had a diameter only half that of the natural product.

“We were blown away by this result,” says Lovley. The conductivity of biowire exceeds that of many types of chemically-produced organic nanowires with similar diameters. The extremely thin diameter of 1.5 nanometers (over 60,000 times thinner than a human hair) means that thousands of the wires can easily be packed into a very small space.

The added benefit is that making biowire does not require any of the dangerous chemicals that are needed for synthesis of other nanowires. Also, biowire contains no toxic components. “Geobacter can be grown on cheap renewable organic feedstocks so it is a very ‘green’ process,” he notes. And, although the biowire is made out of protein, it is extremely durable. In fact, Lovley’s lab had to work for months to establish a method to break it down.

“It’s quite an unusual protein,” Lovley says. “This may be just the beginning” he adds. Researchers in his lab recently produced more than 20 other Geobacter strains, each producing a distinct biowire variant with new amino acid combinations. He notes, “I am hoping that our initial success will attract more funding to accelerate the discovery process. We are hoping that we can modify biowire in other ways to expand its potential applications.”

As it often does, funding provides some notes of interest,

This research was supported by the Office of Naval Research, the National Science Foundation’s Nanoscale Science and Engineering Center and the UMass Amherst Center for Hierarchical Manufacturing.

Caption: Synthetic biowire are making an electrical connection between two electrodes. Researchers led by microbiologist Derek Lovely at UMass Amherst say the wires, which rival the thinnest wires known to man, are produced from renewable, inexpensive feedstocks and avoid the harsh chemical processes typically used to produce nanoelectronic materials. Credit: UMass Amherst

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Synthetic Biological Protein Nanowires with High Conductivity by Yang Tan, Ramesh Y. Adhikari, Nikhil S. Malvankar, Shuang Pi, Joy E. Ward, Trevor L. Woodard, Kelly P. Nevin, Qiangfei Xia, Mark T. Tuominen, and Derek R. Lovley. Small DOI: 10.1002/smll.201601112 Version of Record online: 13 JUL 2016

© 2016 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

This paper is behind a paywall.