For all the talk about research with stem cells, it seems they’re not that easy to produce. An April 10, 2017 news item on ScienceDaily describes the problem and how a research team at Iowa State University may have developed a solution,

Researchers looking for ways to regenerate nerves can have a hard time obtaining key tools of their trade.

Schwann cells are an example. They form sheaths around axons, the tail-like parts of nerve cells that carry electrical impulses. They promote regeneration of those axons. And they secrete substances that promote the health of nerve cells.

In other words, they’re very useful to researchers hoping to regenerate nerve cells, specifically peripheral nerve cells, those cells outside the brain and spinal cord.

But Schwann cells are hard to come by in useful numbers.

So researchers have been taking readily available and noncontroversial mesenchymal stem cells (also called bone marrow stromal stem cells that can form bone, cartilage and fat cells) and using a chemical process to turn them, or as researchers say, differentiate them into Schwann cells. But it’s an arduous, step-by-step and expensive process.

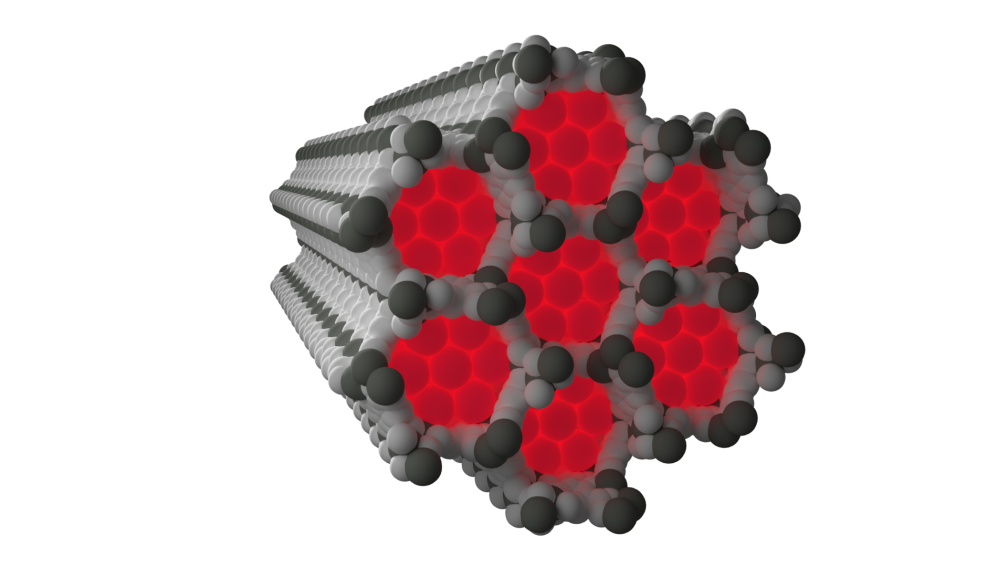

Researchers at Iowa State University are exploring what they hope will be a better way to transform those stem cells into Schwann-like cells. They’ve developed a nanotechnology that uses inkjet printers to print multi-layer graphene circuits and also uses lasers to treat and improve the surface structure and conductivity of those circuits.

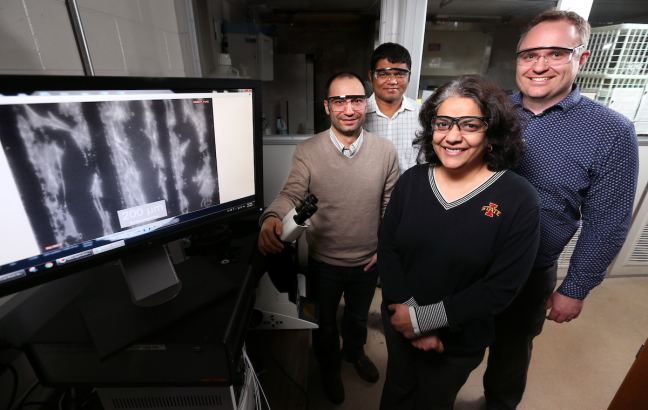

Iowa State University researchers, left to right, Metin Uz, Suprem Das, Surya Mallapragada and Jonathan Claussen are developing technologies to promote nerve regrowth. The monitor shows mesenchymal stem cells (the white) aligned along graphene circuits (the black). Credit: Photo by Christopher Gannon/Iowa State University

An April 10, 2017 Iowa State University news release, which originated the news item, provides more details about the problems with the current process and the possible solution (Note: Links have been removed),

It turns out mesenchymal stem cells adhere and grow well on the treated circuit’s raised, rough and 3-D nanostructures. Add small doses of electricity – 100 millivolts for 10 minutes per day over 15 days – and the stem cells become Schwann-like cells.

The researchers’ findings are featured on the front cover of the scientific journal Advanced Healthcare Materials. Jonathan Claussen, an Iowa State assistant professor of mechanical engineering and an associate of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory, is lead author. Suprem Das, a postdoctoral research associate in mechanical engineering and an associate of the Ames Laboratory; and Metin Uz, a postdoctoral research associate in chemical and biological engineering, are first authors.

The project is supported by funds from the Roy J. Carver Charitable Trust, the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command, Iowa State’s College of Engineering, the department of mechanical engineering and the Carol Vohs Johnson Chair in Chemical and Biological Engineering held by Surya Mallapragada, an Anson Marston Distinguished Professor in Engineering, an associate of the Ames Laboratory and a paper co-author.

“This technology could lead to a better way to differentiate stem cells,” Uz said. “There is huge potential here.”

The electrical stimulation is very effective, differentiating 85 percent of the stem cells into Schwann-like cells compared to 75 percent by the standard chemical process, according to the research paper. The electrically differentiated cells also produced 80 nanograms per milliliter of nerve growth factor compared to 55 nanograms per milliliter for the chemically treated cells.

The researchers report the results could lead to changes in how nerve injuries are treated inside the body.

“These results help pave the way for in vivo peripheral nerve regeneration where the flexible graphene electrodes could conform to the injury site and provide intimate electrical stimulation for nerve cell regrowth,” the researchers wrote in a summary of their findings.

The paper reports several advantages to using electrical stimulation to differentiate stem cells into Schwann-like cells:

- doing away with the arduous steps of chemical processing

- reducing costs by eliminating the need for expensive nerve growth factors

- potentially increasing control of stem cell differentiation with precise electrical stimulation

- and creating a low maintenance, artificial framework for neural damage repairs.

A key to making it all work is a graphene inkjet printing process developed in Claussen’s research lab. The process takes advantages of graphene’s wonder-material properties – it’s a great conductor of electricity and heat, it’s strong, stable and biocompatible – to produce low-cost, flexible and even wearable electronics.

But there was a problem: once graphene electronic circuits were printed, they had to be treated to improve electrical conductivity. That usually meant high temperatures or chemicals. Either could damage flexible printing surfaces including plastic films or paper.

Claussen and his research group solved the problem by developing computer-controlled laser technology that selectively irradiates inkjet-printed graphene oxide. The treatment removes ink binders and reduces graphene oxide to graphene – physically stitching together millions of tiny graphene flakes. The process makes electrical conductivity more than a thousand times better.

The collaboration of Claussen’s group of nanoengineers developing printed graphene technologies and Mallapragada’s group of chemical engineers working on nerve regeneration began with some informal conversations on campus.

That led to experimental attempts to grow stem cells on printed graphene and then to electrical stimulation experiments.

“We knew this would be a really good platform for electrical stimulation,” Das said. “But we didn’t know it would differentiate these cells.”

But now that it has, the researchers say there are new possibilities to think about. The technology, for example, could one day be used to create dissolvable or absorbable nerve regeneration materials that could be surgically placed in a person’s body and wouldn’t require a second surgery to remove.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Stem Cell Differentiation: Electrical Differentiation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells into Schwann-Cell-Like Phenotypes Using Inkjet-Printed Graphene Circuits by Suprem R. Das, Metin Uz, Shaowei Ding, Matthew T. Lentner, John A. Hondred, Allison A. Cargill, Donald S. Sakaguchi, Surya Mallapragada, Jonathan C. Claussen. Advanced Healthcare Materials Volume 6, Issue 7

April 5, 2017) DOI: 10.1002/adhm.201770032

I expect this paper is behind a paywall.