Aalto University (Finland) was the lead research institution for INFERNOS, a European Union-funded project concerning Maxwell’s demon. Here’s an excerpt from an Oct. 14, 2013 post featuring the project,

An Oct. 9, 2013 news item on Nanowerk ties together INFERNOS and the ‘demon’,

Maxwell’s Demon is an imaginary creature that the mathematician James Clerk Maxwell created in 1897. The creature could turn heat into work without causing any other change, which violates the second law of thermodynamics. The primary goal of the European project INFERNOS (Information, fluctuations, and energy control in small systems) is to realize experimentally Maxwell’s Demon; in other words, to develop the electronic and biomolecular nanodevices that support this principle.

…

I like the INFERNOS logo, demon and all,

A Jan. 11, 2016 news item on Nanowerk seems to be highlighting a paper resulting from the INFERNOS project (Note: A link has been removed),

On [a] theoretical level, the thought experiment has been an object of consideration for nearly 150 years, but testing it experimentally has been impossible until the last few years. Making use of nanotechnology, scientists from Aalto University have now succeeded in constructing an autonomous Maxwell’s demon that makes it possible to analyse the microscopic changes in thermodynamics. The research results were recently published in Physical Review Letters (“On-Chip Maxwell’s Demon as an Information-Powered Refrigerator”). The work is part of the forthcoming PhD thesis of MSc Jonne Koski at Aalto University.

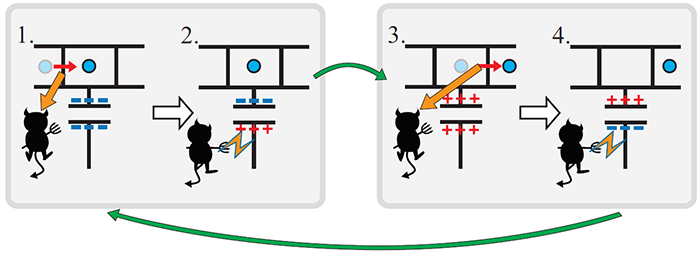

An image illustrating the theory underlying the proposed device has been made available,

An autonomous Maxwell’s demon. When the demon sees the electron enter the island (1.), it traps the electron with a positive charge (2.). When the electron leaves the island (3.), the demon switches back a negative charge (4.). Image: Jonne Koski.

A Jan. 11, 2016 Aalto University press release, which originated the news item, provides more technical details,

The system we constructed is a single-electron transistor that is formed by a small metallic island connected to two leads by tunnel junctions made of superconducting materials. The demon connected to the system is also a single-electron transistor that monitors the movement of electrons in the system. When an electron tunnels to the island, the demon traps it with a positive charge. Conversely, when an electron leaves the island, the demon repels it with a negative charge and forces it to move uphill contrary to its potential, which lowers the temperature of the system,’ explains Professor Jukka Pekola.

What makes the demon autonomous or self-contained is that it performs the measurement and feedback operation without outside help. Changes in temperature are indicative of correlation between the demon and the system, or, in simple terms, of how much the demon ‘knows’ about the system. According to Pekola, the research would not have been possible without the Low Temperature Laboratory conditions.

‘We work at extremely low temperatures, so the system is so well isolated that it is possible to register extremely small temperature changes,’ he says.

‘An electronic demon also enables a very large number of repetitions of the measurement and feedback operation in a very short time, whereas those who, elsewhere in the world, used molecules to construct their demons had to contend with not more than a few hundred repetitions.’

The work of the team led by Pekola remains, for the time being, basic research, but in the future, the results obtained may, among other things, pave the way towards reversible computing.

‘As we work with superconducting circuits, it is also possible for us to create qubits of quantum computers. Next, we would like to examine these same phenomena on the quantum level,’ Pekola reveals.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

On-Chip Maxwell’s Demon as an Information-Powered Refrigerator by J.V. Koski, A. Kutvonen, I.M. Khaymovich, T. Ala-Nissila, and J.P. Pekola. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 260602 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.115.260602 Published 30 December 2015

This paper is behind a paywall.

One final comment, this is the 150th anniversary of Maxwell’s publication of a series of equations explaining the relationships between electric charges and electric and magnetic fields (featured here in a Nov. 27, 2015 posting).

![Original manuscript of Maxwell’s seminal paper Photograph: Jon Butterworth/Royal Society [downloaded from http://www.theguardian.com/science/life-and-physics/2015/nov/22/maxwells-equations-150-years-of-light]](http://www.frogheart.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/MaxwellsUnificationTheory.jpg)