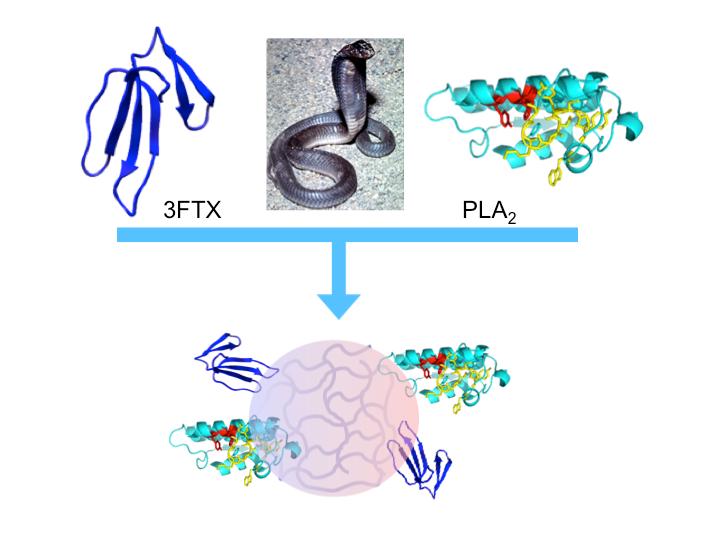

This is an image illustrating the work but you’ll probably need to read the news release to understand the explanation offered,

The research from the University of California at Irvine (UCI) has been featured twice, in an August 31, 2023 news item on phys.org and again in a September 7, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily.

An August 29, 2023 UCI news release (also on EurekAlert but published Sept. 6, 2023), which originated the news items, provides information about RP and the nanobodies,

A team of scientists from the University of California, Irvine, believe they have discovered a special antibody which may lead to a treatment for Retinitis Pigmentosa, a condition that causes loss of central vision, as well as night and color vision.

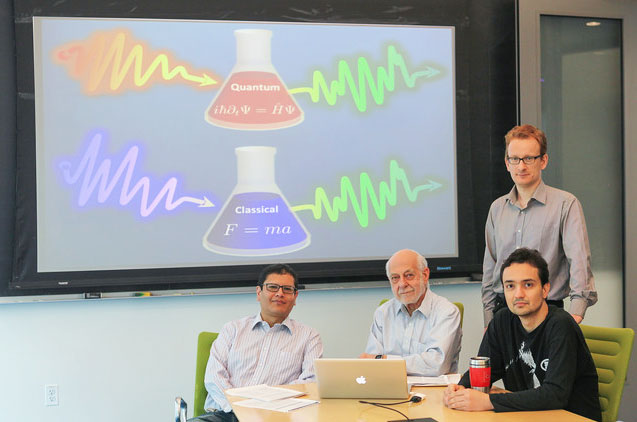

The study, Structural basis for the allosteric modulation of rhodopsin by nanobody binding to its extracellular domain, was published in Nature Communications. Authors of the study were Arum Wu, PhD, David Salom, PhD, John D. Hong, Aleksander Tworak, PhD, Philip D. Kiser, PharmD, PhD, and Krzysztof Palczewski, PhD, in the Department of Ophthalmology, Gavin Herbert Eye Institute, at the University of California, Irvine. Research was conducted in collaboration with Jan Steyaert, PhD, at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB).

Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) is a group of inherited eye diseases that affect the retina in the back of the eye. It is caused by the death of cells that detect light signals, known as photoreceptor cells. There is no known cure for RP, and the development of new treatments for this condition relies on cell and gene therapies.

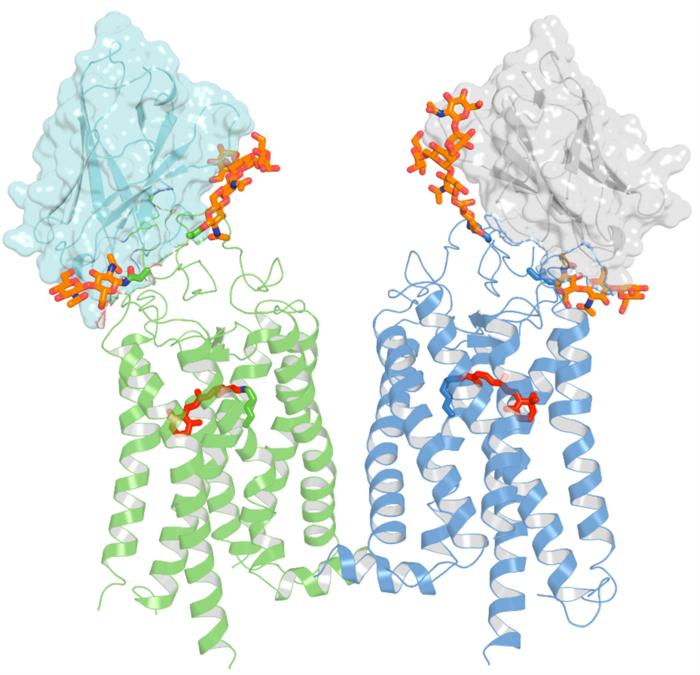

UCI researchers have targeted their study on a specific molecule which they believe will provide a treatment for Rhodopsin-associated autosomal dominant RP (adRP). The molecule, Rhodopsin, is a key light-sensing molecule in the human retina. It is found in rod photoreceptor cells, and mutations in the Rhodopsin gene are a primary cause of adRP.

“More than 150 mutations in rhodopsin can cause Retinitis Pigmentosa, making it challenging to develop targeted gene therapies,” said Krzysztof Palczewski, PhD, Donald Bren Professor, UCI School of Medicine. “However due to the high prevalence of RP, there has been significant investment in research and development efforts to find novel treatments.”

Although Rhodopsin has been studied for over a century, key details of its mechanism for converting light into a cellular signal have been difficult to experimentally address.

For this study, researchers used a special type of llama-derived antibody, known as a nanobody, that can halt the process of Rhodopsin photoactivation, allowing it to be investigated at high resolution.

“Our team has developed nanobodies that work through a novel mechanism of action. These nanobodies have high specificity and can recognize the target rhodopsin extracellularly,” said David Salom , PhD, researcher and project scientist, UCI School of Medicine. “This enables us to lock this GPCR in a non-signaling state.”

Scientists discovered that these nanobodies target an unexpected site on the Rhodopsin molecule, near the location where retinaldehyde binds. They also found that the stabilizing effect of these nanobodies can also be applied to Rhodopsin mutants that are associated with retinal disease, suggesting their use as therapeutics.

“In the future, we hope to involve the in vitro evolution of these initial set of nanobodies,” said Arum Wu, PhD, researcher and project scientist, UCI School of Medicine. “We will also evaluate the safety and effectiveness of a future nanobody gene therapy for RP.”

Researchers hope to improve nanobodies’ ability to recognize Rhodopsin from other species including mice, for which several pre-clinical models of adRP are available. They also have plans to use these nanobodies to address a long-term goal in the field of structurally resolving the key intermediate states of Rhodopsin from the inactive state to the fully ligand-activated state.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Structural basis for the allosteric modulation of rhodopsin by nanobody binding to its extracellular domain by Arum Wu, David Salom, John D. Hong, Aleksander Tworak, Kohei Watanabe, Els Pardon, Jan Steyaert, Hideki Kandori, Kota Katayama, Philip D. Kiser & Krzysztof Palczewski. Nature Communications volume 14, Article number: 5209 (2023) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-023-40911-9 Published: 25 August 2023

This paper is open access.