The deformation properties of nanocrystals resemble those in the earth’s crust according to a Nov. 17, 2015 news item on Nanowerk,

Apparently, size doesn’t always matter. An extensive study by an interdisciplinary research group suggests that the deformation properties of nanocrystals are not much different from those of the Earth’s crust.

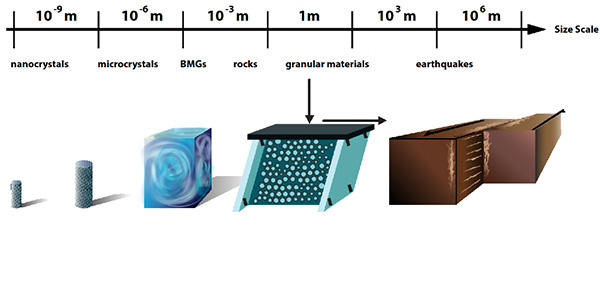

“When solid materials such as nanocrystals, bulk metallic glasses, rocks, or granular materials are slowly deformed by compression or shear, they slip intermittently with slip-avalanches similar to earthquakes,” explained Karin Dahmen, a professor of physics at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “Typically these systems are studied separately. But we found that the scaling behavior of their slip statistics agree across a surprisingly wide range of different length scales and material structures.”

There’s an illustration accompanying the research,

Caption: When solid materials such as nanocrystals, bulk metallic glasses, rocks, or granular materials are slowly deformed by compression or shear, they slip intermittently with slip-avalanches similar to earthquakes. Credit: University of Illinois

A Nov. 17, 2015 University of Illinois news release (also on EurekAlert) by Rick Kubetz, which originated the news item, provides more detail,

“Identifying agreement in aspects of the slip statistics is important, because it enables us to transfer results from one scale to another, from one material to another, from one stress to another, or from one strain rate to another,” stated Shivesh Pathak, a physics undergraduate at Illinois, and a co-author of the paper, “Universal Quake Statistics: From Compressed Nanocrystals to Earthquakes,” appearing in Scientific Reports. “The study shows how to identify and explain commonalities in the deformation mechanisms of different materials on different scales.

“The results provide new tools and methods to use the slip statistics to predict future materials deformation,” added Michael LeBlanc, a physics graduate student and co-author of the paper. “They also clarify which system parameters significantly affect the deformation behavior on long length scales. We expect the results to be useful for applications in materials testing, failure prediction, and hazard prevention.”

Researchers representing a broad a range of disciplines–including physics, geosciences, mechanical engineering, chemical engineering, and materials science–from the United States, Germany, and the Netherlands contributed to the study, comparing five different experimental systems, on several different scales, with model predictions.

As a solid is sheared, each weak spot is stuck until the local shear stress exceeds a random failure threshold. It then slips by a random amount until it re-sticks. The released stress is redistributed to all other weak spots. Thus, a slipping weak spot can trigger other spots to fail in a slip avalanche.

Using tools from the theory of phase transitions, such as the renormalization group, one can show that the slip statistics of the model do not depend on the details of the system.

“Although these systems span 13 decades in length scale, they all show the same scaling behavior for their slip size distributions and other statistical properties,” stated Pathak. “Their size distributions follow the same simple (power law) function, multiplied with the same exponential cutoff.”

The cutoff, which is the largest slip or earthquake size, grows with applied force for materials spanning length scales from nanometers to kilometers. The dependence of the size of the largest slip or quake on stress reflects “tuned critical” behavior, rather than so-called self-organized criticality, which would imply stress-independence.

“The agreement of the scaling properties of the slip statistics across scales does not imply the predictability of individual slips or earthquakes,” LeBlanc said. “Rather, it implies that we can predict the scaling behavior of average properties of the slip statistics and the probability of slips of a certain size, including their dependence on stress and strain-rate.”

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Universal Quake Statistics: From Compressed Nanocrystals to Earthquakes by Jonathan T. Uhl, Shivesh Pathak, Danijel Schorlemmer, Xin Liu, Ryan Swindeman, Braden A. W. Brinkman, Michael LeBlanc, Georgios Tsekenis, Nir Friedman, Robert Behringer, Dmitry Denisov, Peter Schall, Xiaojun Gu, Wendelin J. Wright, Todd Hufnagel, Andrew Jennings, Julia R. Greer, P. K. Liaw, Thorsten Becker, Georg Dresen, & Karin A. Dahmen. Scientific Reports 5, Article number: 16493 (2015) doi:10.1038/srep16493 Published online: 17 November 2015

This is an open access paper.

One final comment, this story reminds me of a few other pieces of research featured here, which focus on repeating patterns in nature. The research was mentioned in an Aug. 27, 2015 posting about white dwarf stars and heartbeats and in an April 14, 2015 posting about gold nanoparticles and their resemblance to the Milky Way. You can also find more in the Wikipedia entry titled ‘Patterns in nature‘.