An April 30, 2021 news item on ScienceDaily announces the research,

Researchers in the Nanoscience Center of University of Jyvaskyla, in Finland and in the Guadalajara University in Mexico developed a method that allows for simulation and visualization of magnetic-field-induced electron currents inside gold nanoparticles. The method facilitates accurate analysis of magnetic field effects inside complex nanostructures in nuclear magnetic resonance measurements and establishes quantitative criteria for aromaticity of nanoparticles. The work was published 30.4.2021 as an Open Access article in Nature Communications.

An April 30, 2021 University of Jyväskylä – Jyväskylän yliopisto news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, describes the work in greater technical detail,

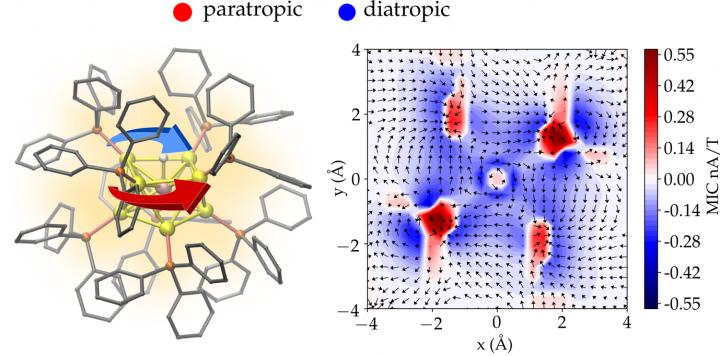

According to the classical electromagnetism, a charged particle moving in an external magnetic field experiences a force that makes the particle’s path circular. This basic law of physics is used, e.g., in designing cyclotrons that work as particle accelerators. When nanometer-size metal particles are placed in a magnetic field, the field induces a circulating electron current inside the particle. The circulating current in turn creates an internal magnetic field that opposes the external field. This physical effect is called magnetic shielding.

The strength of the shielding can be investigated by using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. The internal magnetic shielding varies strongly in an atomic length scale even inside a nanometer-size particle. Understanding these atom-scale variations is possible only by employing quantum mechanical theory of the electronic properties of each atom making the nanoparticle.

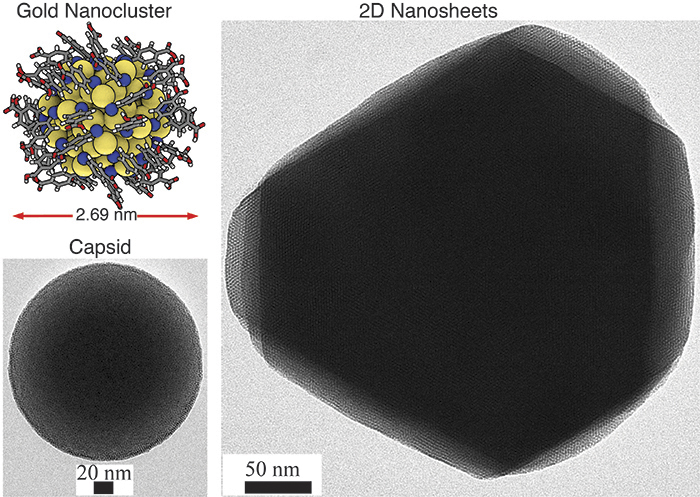

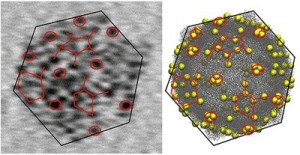

Now, the research group of Professor Hannu Häkkinen in the University of Jyväskylä, in collaboration with University of Guadalajara in Mexico, developed a method to compute, visualize, and analyze the circulating electron currents inside complex 3D nanostructures. The method was applied to gold nanoparticles with a diameter of only about one nanometer. The calculations shed light onto unexplained experimental results from previous NMR measurements in the literature regarding how magnetic shielding inside the particle changes when one gold atom is replaced by one platinum atom.

A new quantitative measure to characterize aromaticity inside metal nanoparticles was also developed based on the total integrated strength of the shielding electron current.

“Aromaticity of molecules is one of the oldest concepts in chemistry, and it has been traditionally connected to ring-like organic molecules and to their delocalized valence electron density that can develop circulating currents in an external magnetic field. However, generally accepted quantitative criteria for the degree of aromaticity have been lacking. Our method yields now a new tool to study and analyze electron currents at the resolution of one atom inside any nanostructure, in principle. The peer reviewers of our work considered this as a significant advancement in the field”, says Professor Häkkinen who coordinated the research.

This image illustrates the work,

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Magnetically induced currents and aromaticity in ligand-stabilized Au and AuPt superatoms by Omar López-Estrada, Bernardo Zuniga-Gutierrez, Elli Selenius, Sami Malola & Hannu Häkkinen . Nature Communications volume 12, Article number: 2477 (2021) DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22715 Published: 30 April 2021

This paper is open access.