This looks like one robot operating on another robot; I guess the researchers want to emphasize the fact that this autonomous surgical procedure isn’t currently being tested on human beings.

There’s more in a September 21, 2023 news item on ScienceDaily,

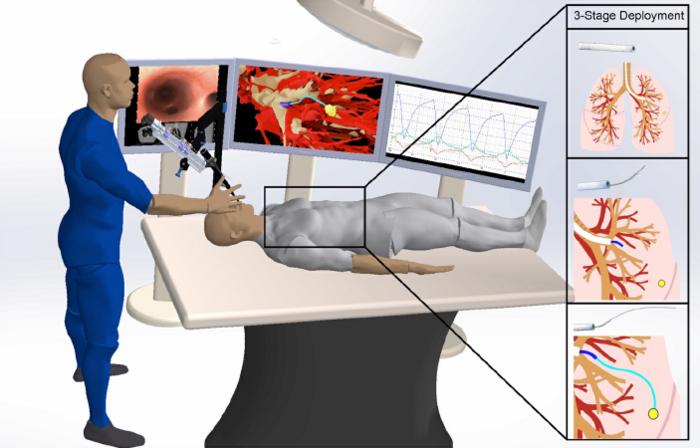

Scientists have shown that their steerable lung robot can autonomously maneuver the intricacies of the lung, while avoiding important lung structures.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States. Some tumors are extremely small and hide deep within lung tissue, making it difficult for surgeons to reach them. To address this challenge, UNC -Chapel Hill and Vanderbilt University researchers have been working on an extremely bendy but sturdy robot capable of traversing lung tissue.

Their research has reached a new milestone. In a new paper, published in Science Robotics, Ron Alterovitz, PhD, in the UNC Department of Computer Science, and Jason Akulian, MD MPH, in the UNC Department of Medicine, have proven that their robot can autonomously go from “Point A” to “Point B” while avoiding important structures, such as tiny airways and blood vessels, in a living laboratory model.

…

Thankfully there’s a September 21, 2023 University of North Carolina (UNC) news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, to provide more information, Note: Links have been removed,

“This technology allows us to reach targets we can’t otherwise reach with a standard or even robotic bronchoscope,” said Dr. Akulian, co-author on the paper and Section Chief of Interventional Pulmonology and Pulmonary Oncology in the UNC Division of Pulmonary Disease and Critical Care Medicine. “It gives you that extra few centimeters or few millimeters even, which would help immensely with pursuing small targets in the lungs.”

The development of the autonomous steerable needle robot leveraged UNC’s highly collaborative culture by blending medicine, computer science, and engineering expertise. In addition to Alterovitz and Akulian, the development effort included Yueh Z. Lee, MD, PhD, at the UNC Department of Radiology, as well as Robert J. Webster III at Vanderbilt University and Alan Kuntz at the University of Utah.

The robot is made of several separate components. A mechanical control provides controlled thrust of the needle to go forward and backward and the needle design allows for steering along curved paths. The needle is made from a nickel-titanium alloy and has been laser etched to increase its flexibility, allowing it to move effortlessly through tissue.

As it moves forward, the etching on the needle allows it to steer around obstacles with ease. Other attachments, such as catheters, could be used together with the needle to perform procedures such as lung biopsies.

To drive through tissue, the needle needs to know where it is going. The research team used CT scans of the subject’s thoracic cavity and artificial intelligence to create three-dimensional models of the lung, including the airways, blood vessels, and the chosen target. Using this 3-D model and once the needle has been positioned for launch, their AI-driven software instructs it to automatically travel from “Point A” to “Point B” while avoiding important structures.

“The autonomous steerable needle we’ve developed is highly compact, but the system is packed with a suite of technologies that allow the needle to navigate autonomously in real-time,” said Alterovitz, the principal investigator on the project and senior author on the paper. “It’s akin to a self-driving car, but it navigates through lung tissue, avoiding obstacles like significant blood vessels as it travels to its destination.”

The needle can also account for respiratory motion. Unlike other organs, the lungs are constantly expanding and contracting in the chest cavity. This can make targeting especially difficult in a living, breathing subject. According to Akulian, it’s like shooting at a moving target.

The researchers tested their robot while the laboratory model performed intermittent breath holding. Every time the subject’s breath is held, the robot is programmed to move forward.

“There remain some nuances in terms of the robot’s ability to acquire targets and then actually get to them effectively,” said Akulian, who is also a member of the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, “and while there’s still a lot of work to be done, I’m very excited about continuing to push the boundaries of what we can do for patients with the world-class experts that are here.”

“We plan to continue creating new autonomous medical robots that combine the strengths of robotics and AI to improve medical outcomes for patients facing a variety of health challenges while providing guarantees on patient safety,” added Alterovitz.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Autonomous medical needle steering in vivo by Alan Kuntz, Maxwell Emerson, Tayfun Efe Ertop, Inbar Fried, Mengyu Fu, Janine Hoelscher, Margaret Rox, Jason Akulian, Erin A. Gillaspie, Yueh Z. Lee, Fabien Maldonado, Robert J. Webster III, and Ron Alterovitz. Science Robotics 20 Sep 2023 Vol 8, Issue 82 DOI: 10.1126/scirobotics.adf7614

This paper is behind a paywall.