A May 24, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily describes the latest research on using diamonds as semiconductors,

Along with being a “girl’s best friend,” diamonds also have remarkable properties that could make them ideal semiconductors. This is welcome news for electronics; semiconductors are needed to meet the rising demand for more efficient electronics that deliver and convert power.

The thirst for electronics is unlikely to cease and almost every appliance or device requires a suite of electronics that transfer, convert and control power. Now, researchers have taken an important step toward that technology with a new way to dope single crystals of diamonds, a crucial process for building electronic devices.

A May 24, 2016 American Institute of Physics (AIP) news release (also on EurekAlert), which originated the news item, provides more detail,

For power electronics, diamonds could serve as the perfect material. They are thermally conductive, which means diamond-based devices would dissipate heat quickly and easily, foregoing the need for bulky and expensive methods for cooling. Diamond can also handle high voltages and power. Electrical currents also flow through diamonds quickly, meaning the material would make for energy efficient devices.

But among the biggest challenges to making diamond-based devices is doping, a process in which other elements are integrated into the semiconductor to change its properties. Because of diamond’s rigid crystalline structure, doping is difficult.

Currently, you can dope diamond by coating the crystal with boron and heating it to 1450 degrees Celsius. But it’s difficult to remove the boron coating at the end. This method only works on diamonds consisting of multiple crystals stuck together. Because such polydiamonds have irregularities between the crystals, single-crystals would be superior semiconductors.

You can dope single crystals by injecting boron atoms while growing the crystals artificially. The problem is the process requires powerful microwaves that can degrade the quality of the crystal.

Now, Ma [Zhengqiang (Jack) Ma, an electrical and computer engineering professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison] and his colleagues have found a way to dope single-crystal diamonds with boron at relatively low temperatures and without any degradation. The researchers discovered if you bond a single-crystal diamond with a piece of silicon doped with boron, and heat it to 800 degrees Celsius, which is low compared to the conventional techniques, the boron atoms will migrate from the silicon to the diamond. It turns out that the boron-doped silicon has defects such as vacancies, where an atom is missing in the lattice structure. Carbon atoms from the diamond will fill those vacancies, leaving empty spots for boron atoms.

This technique also allows for selective doping, which means more control when making devices. You can choose where to dope a single-crystal diamond simply by bonding the silicon to that spot.

The new method only works for P-type doping, where the semiconductor is doped with an element that provides positive charge carriers (in this case, the absence of electrons, called holes).

“We feel like we found a very easy, inexpensive, and effective way to do it,” Ma said. The researchers are already working on a simple device using P-type single-crystal diamond semiconductors.

But to make electronic devices like transistors, you need N-type doping that gives the semiconductor negative charge carriers (electrons). And other barriers remain. Diamond is expensive and single crystals are very small.

Still, Ma says, achieving P-type doping is an important step, and might inspire others to find solutions for the remaining challenges. Eventually, he said, single-crystal diamond could be useful everywhere — perfect, for instance, for delivering power through the grid.

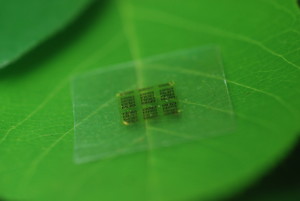

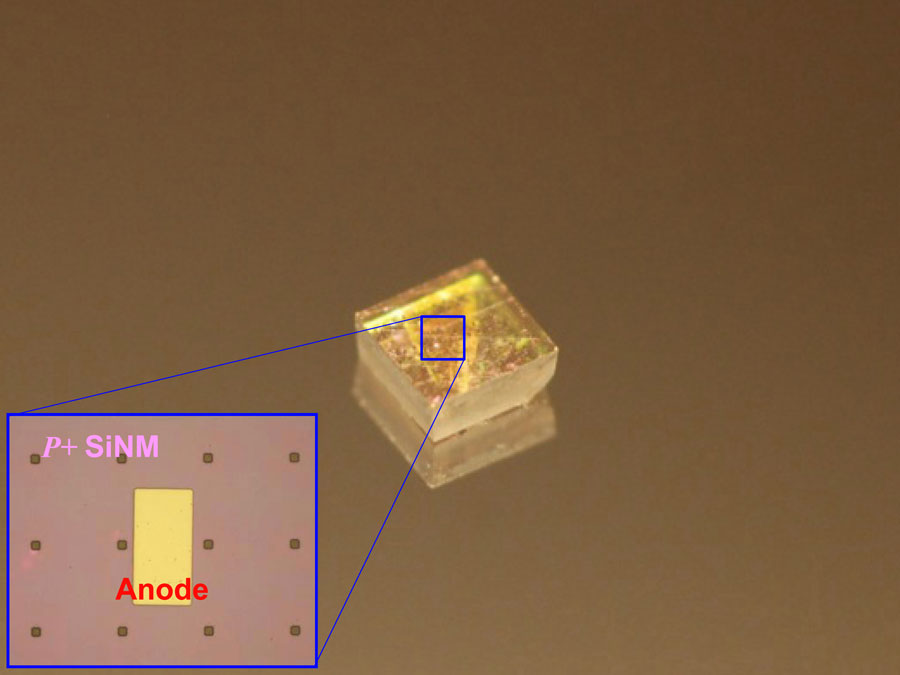

Here’s an image the researchers have released,

Optical image of a diode array on a natural single crystalline diamond plate. (The image looks blurred due to light scattering by the array of small pads on top of the diamond plate.) Inset shows the deposited anode metal on top of heavy doped Si nanomembrane that is bonded to natural single crystalline diamond. CREDIT: Jung-Hun Seo Courtesy: American Institute of Physics

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Thermal diffusion boron doping of single-crystal natural diamond by Jung-Hun Seo, Henry Wu, Solomon Mikael, Hongyi Mi, James P. Blanchard, Giri Venkataramanan, Weidong Zhou, Shaoqin Gong, Dane Morgan, and Zhenqiang Ma. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 205703 (2016); http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4949327

This paper appears to be open access.