It’s good to wake up to something truly new. In this case, it’s using tattoos and nanoparticles for medical applications. From a Sept. 22, 2016 news item on ScienceDaily,

A temporary tattoo to help control a chronic disease might someday be possible, according to scientists at Baylor College of Medicine [Texas, US] who tested antioxidant nanoparticles created at Rice University [Texas, US].

A Sept. 22, 2016 Rice University news release, which originated the news item, provides more information and some good explanations of the terms used (Note: Links have been removed),

A proof-of-principle study led by Baylor scientist Christine Beeton published today by Nature’s online, open-access journal Scientific Reports shows that nanoparticles modified with polyethylene glycol are conveniently choosy as they are taken up by cells in the immune system.

That could be a plus for patients with autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis, one focus of study at the Beeton lab. “Placed just under the skin, the carbon-based particles form a dark spot that fades over about one week as they are slowly released into the circulation,” Beeton said.

T and B lymphocyte cells and macrophages are key components of the immune system. However, in many autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, T cells are the key players. One suspected cause is that T cells lose their ability to distinguish between invaders and healthy tissue and attack both.

In tests at Baylor, nanoparticles were internalized by T cells, which inhibited their function, but ignored by macrophages. “The ability to selectively inhibit one type of cell over others in the same environment may help doctors gain more control over autoimmune diseases,” Beeton said.

“The majority of current treatments are general, broad-spectrum immunosuppressants,” said Redwan Huq, lead author of the study and a graduate student in the Beeton lab. “They’re going to affect all of these cells, but patients are exposed to side effects (ranging) from infections to increased chances of developing cancer. So we get excited when we see something new that could potentially enable selectivity.” Since the macrophages and other splenic immune cells are unaffected, most of a patient’s existing immune system remains intact, he said.

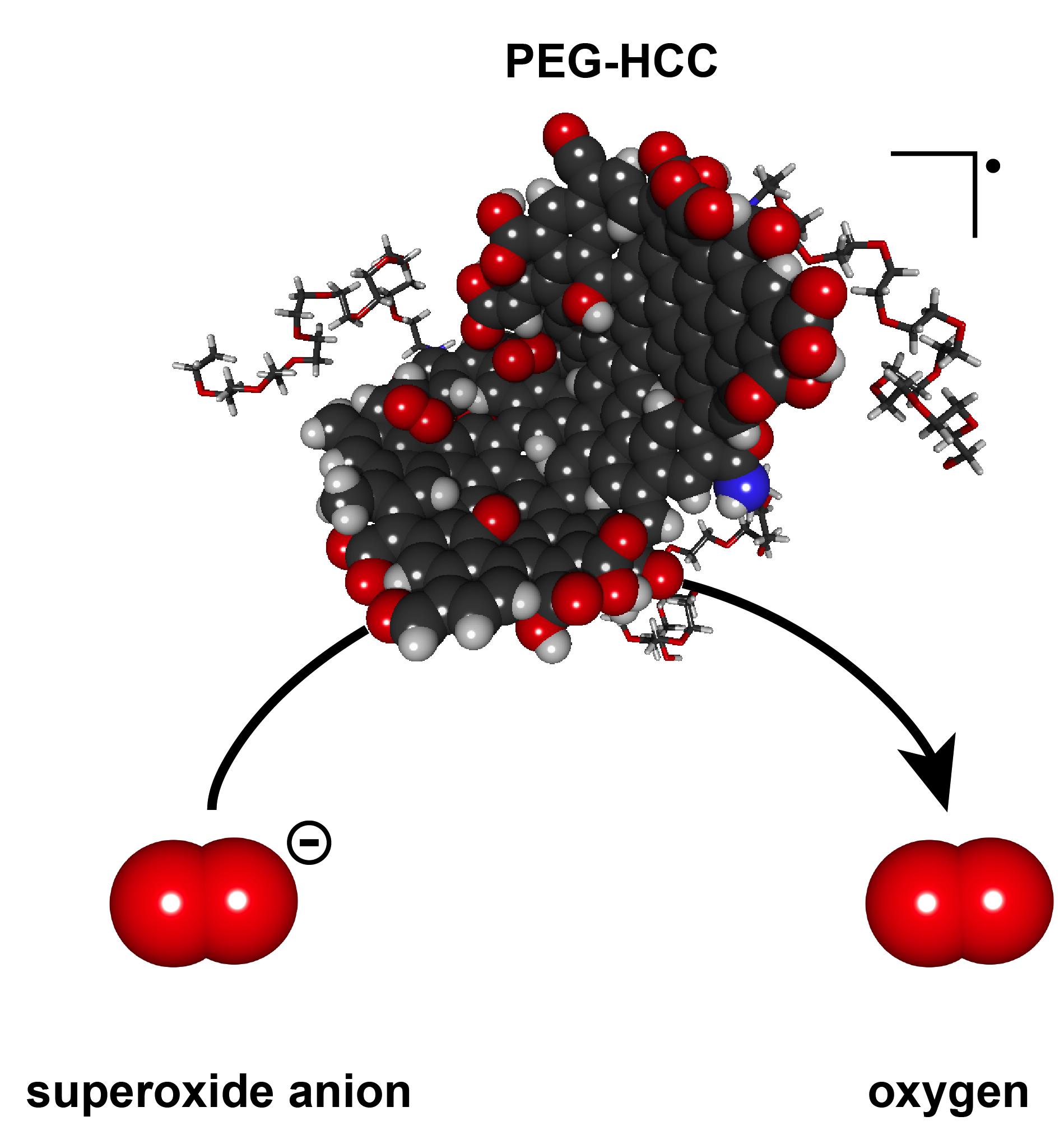

The soluble nanoparticles synthesized by the Rice lab of chemist James Tour have shown no signs of acute toxicity in prior rodent studies, Huq said. They combine polyethylene glycol with hydrophilic carbon clusters, hence their name, PEG-HCCs. The carbon clusters are 35 nanometers long, 3 nanometers wide and an atom thick, and bulk up to about 100 nanometers in globular form with the addition of PEG. They have proven to be efficient scavengers of reactive oxygen species called superoxide molecules, which are expressed by cells the immune system uses to kill invading microorganisms.

T cells use superoxide in a signaling step to become activated. PEG-HCCs remove this superoxide from the T cells, preventing their activation without killing the cells.

Beeton became aware of PEG-HCCs during a presentation by former Baylor graduate student Taeko Inoue, a co-author of the new study. “As she talked, I was thinking, ‘That has to work in models of multiple sclerosis,’” Beeton said. “I didn’t have a good scientific rationale, but I asked for a small sample of PEG-HCCs to see if they affected immune cells.

“We found they affected the T lymphocytes and not the other splenic immune cells, like the macrophages. It was completely unexpected,” she said.

The Baylor lab’s tests on animal models showed that small amounts of PEG-HCCs injected under the skin are slowly taken up by T lymphocytes, where they collect and inhibit the cell’s function. They also found the nanoparticles did not remain in T cells and dispersed within days after uptake by the cells.

“That’s an issue because you want a drug that’s in the system long enough to be effective, but not so long that, if you have a problem, you can’t remove it,” Beeton said. “PEG-HCCs can be administered for slow release and don’t stay in the system for long. This gives us much better control over the circulating half-life.”

“The more we study the abilities of these nanoparticles, the more surprised we are at how useful they could be for medical applications,” Tour said. The Rice lab has published papers with collaborators at Baylor and elsewhere on using functionalized nanoparticles to deliver cancer drugs to tumors and to quench the overproduction of superoxides after traumatic brain injuries.

Beeton suggested delivering carbon nanoparticles just under the skin rather than into the bloodstream would keep them in the system longer, making them more available for uptake by T cells. And the one drawback – a temporary but visible spot on the skin that looks like a tattoo – could actually be a perk to some.

“We saw it made a black mark when we injected it, and at first we thought that’s going to be a real problem if we ever take it into the clinic,” Beeton said. “But we can work around that. We can inject into an area that’s hidden, or use micropattern needles and shape it.

“I can see doing this for a child who wants a tattoo and could never get her parents to go along,” she said. “This will be a good way to convince them.”

The research was supported by Baylor College of Medicine, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, National Institutes of Health, the Dan L. Duncan Cancer Center, John S. Dunn Gulf Coast Consortium for Chemical Genomics and the U.S. Army-funded Traumatic Brain Injury Consortium.

That’s an interesting list of funders at the end of the news release.

Here’s a link to and a citation for the paper,

Preferential uptake of antioxidant carbon nanoparticles by T lymphocytes for immunomodulation by Redwan Huq, Errol L. G. Samuel, William K. A. Sikkema, Lizanne G. Nilewski, Thomas Lee, Mark R. Tanner, Fatima S. Khan, Paul C. Porter, Rajeev B. Tajhya, Rutvik S. Patel, Taeko Inoue, Robia G. Pautler, David B. Corry, James M. Tour, & Christine Beeton. Scientific Reports 6, Article number: 33808 (2016) doi:10.1038/srep33808 Published online: 22 September 2016

This paper is open access.

Here’s an image provided by the researchers,

Polyethylene glycol-hydrophilic carbon clusters developed at Rice University were shown to be selectively taken up by T cells, which inhibits their function, in tests at Baylor College of Medicine. The researchers said the nanoparticles could lead to new strategies for controlling autoimmune diseases like multiple sclerosis. (Credit: Errol Samuel/Rice University)